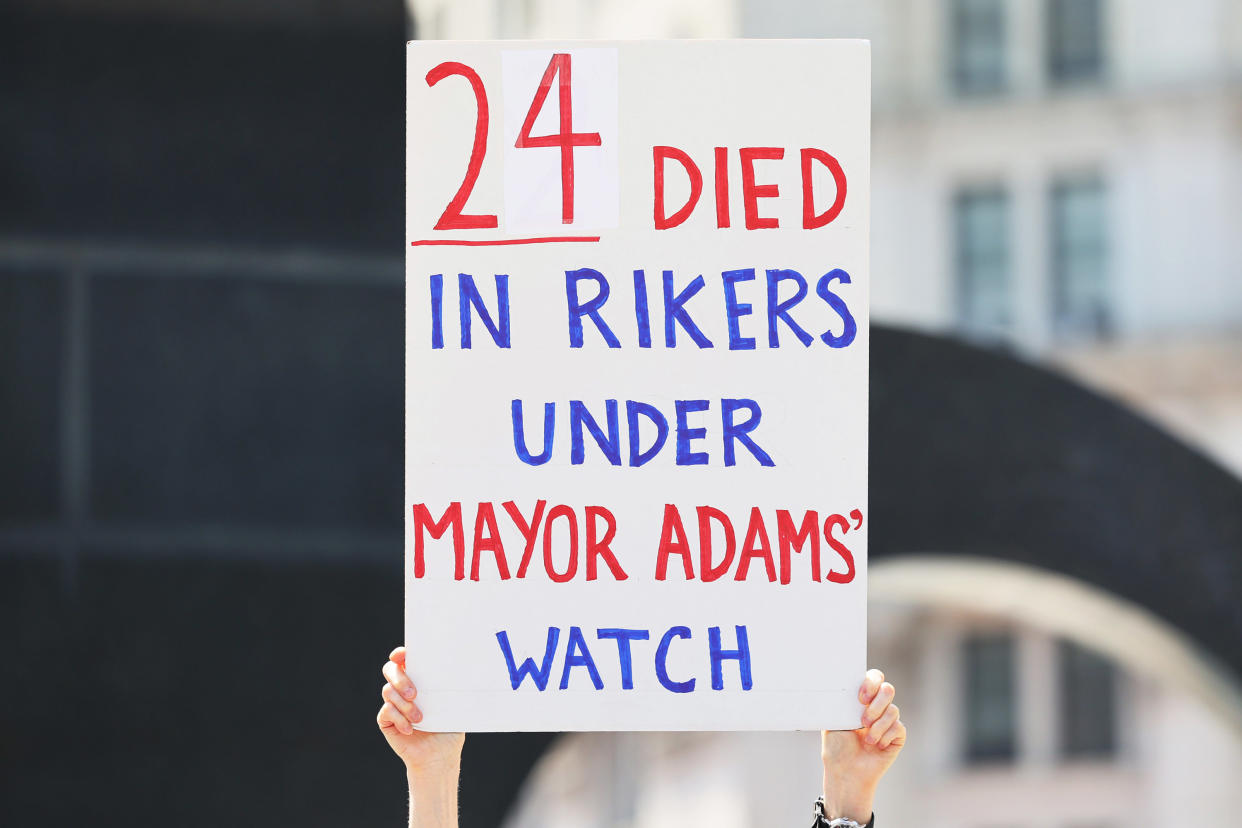

Deaths at Rikers, NYC jails often follow health care staff errors that are rarely disciplined

In the aftermath of Brandon Rodriguez’s 2021 death by suicide at Rikers Island, investigators found a number of serious missteps by jail medical staff, but none resulted in discipline, according to records and interviews.

That’s not unusual. Just two Correctional Health Services staffers have been disciplined in the 44 deaths reported in city jails since January 2021, agency officials confirmed to the Daily News.

Detainee advocates argue that they’ve seen cases mishandled by Correctional Health Service workers who they feel should have been sanctioned.

In Rodriguez’s case, Correctional Health Services staffers failed the day before he died to identify him as a suicide risk — despite his record of mental illness and self-harm. They also failed to give him psychiatric medication and failed to put him in a mental health unit, records show.

“I am asking for help because I cannot stay there,” Rodriguez allegedly told a Correctional Health Services staffer. Rodriguez had been attacked 24 hours into his stay at Rikers and was scared of being placed in general population, his family’s lawyer William Wagstaff said.

The staffer ignored Rodriguez’s plea and didn’t send him to a mental health unit, said Wagstaff. Rodriguez was then shoved into a caged shower stall where he hung himself.

“[The staffer] should definitely have been disciplined, and that’s why she is named in the lawsuit,” Wagstaff said. “It screams negligence in the best case, indifference in the worst case.”

Correctional Health Services staff also failed to provide Rodriguez with medication for his mental condition, Wagstaff said — a belief he said was based on a review of case records. “Any CHS employee who was responsible for the delay in medicating Brandon should have been fired,” he said.

Last Tuesday, the city agreed to settle the lawsuit brought by Rodriguez’s mother, Tamara Carter, for $2.25 million. A court hearing on the settlement is scheduled for January.

The two Correctional Health Services workers who were punished were sanctioned in the case of detainee Marvin Pines, who died Feb. 4 of a seizure.

The two employees were suspended and later quit after botching the use of electric defibrillator paddles to revive Pines and failing to bring a stretcher to his side as he was dying, the city Board of Correction found. Exactly why they were suspended was not made clear before the employees voluntarily left their jobs.

Correctional Health Services’ staffers’ errors contributed to other deaths as well, say investigative reports and lawsuits.

• In the death of Wilson Diaz-Guzman, who hung himself in the Otis Bantum Correctional Center on Jan. 22 2021, the state Commission of Correction found that Correctional Health Services staff failed to secure psychiatric treatment for him after he threatened suicide and cut himself. “[H]ad Diaz-Guzman received proper psychiatric referrals and treatment, his death may have been prevented,” the report said. Correctional Health Services’ response to the finding was redacted from an otherwise public document.

• After Javier Velasco, 37, hanged himself on March 19, 2021, in a mental observation unit at the Anna M. Kross Center, the Commission of Correction found Correctional Health Services staff took him off suicide watch just 36 hours after a previous attempt. The commission also questioned why Velasco wasn’t put in a hospital given a history of suicide attempts. “Velasco’s death was preventable,” the city Board of Correction said. As in the Diaz-Guzman case, Correctional Health Services’ response to the board’s finding was redacted from an otherwise public document.

• After Robert Jackson died on June 30, 2021, of heart disease, the Commission of Correction found there was an “unacceptable” delay in the arrival of medical staff. If medical help had arrived sooner, Jackson could have been saved, the report said.

Correctional Health Services disputed that finding, stating it was notified of Jackson’s medical emergency 68 minutes after the time claimed in Correction Department reports. The Commission of Correction noted “a of conflict of findings between [Correction Department and Correctional Health Services] responses.”

• After Victor Mercado died of COVID-19 on Oct. 15 2021, the Commission of Correction found “multiple deficiencies in medical assessment and treatment” that may have led to his death, including a failure to check his vital signs for 72 hours prior. Correctional Health Services called the findings “incorrect.”

• After Malcolm Boatwright died of a seizure on Dec. 10, 2021, the commission found Correctional Health Services staff “mismanaged” his anti-depressant medication.

Correctional Health Services also called this finding “incorrect” — a statement not elaborated on in the public record. The Commission of Correction said health services didn’t provide medical documentation to back up its claim the finding was “incorrect,” and that it stood by its conclusions.

In the case of Herminio Villanueva, who died of a severe asthma attack while positive for COVID-19 on June 21, 2020, the commission found Correctional Health Services staffers repeatedly failed to give him his medication.

“He needed an inhaled steroid, which reduces swelling in the lungs,” said Katherine Rosenfeld, a lawyer for Villanueva’s family. “But they just kept giving him the less effective Albuterol, which was making him sicker and sicker.”

Correctional Health Services’ response is not noted in the Commission of Correction report.

The health provider often pushes back on the commission’s reports.

Correctional Health Services spokeswoman Jeanette Merrill said that after every in-custody death, the agency conducts a comprehensive review to assess the care that was provided, and also does a joint review of the cases with the Correction Department.

“Any identified areas for improvement are addressed to support the provision of quality health care,” she said.

“Regarding the specific patient cases outlined in the death reports, CHS has provided clarifications and corrections to the oversight bodies, which are publicly available.”

The Commission of Correction often takes more than two years to finalize a report — thus the agency has released final reports in only 10 of the 44 deaths since January 2021.

Lawyers and detainees’ families also raise questions about missteps by Correctional Health Services that are not yet the subject of state commission reports.

Esias Johnson, who overdosed on methadone on Sept 7, 2021, told a Correctional Health Services staffer he was getting the drug from another detainee — but that information was not passed on to the Correction Department, the city Board of Correction found.

“The doctor’s reaction was to continue to prescribe methadone, but they didn’t verify that the amount they were giving him was acceptable,” said the Johnson family’s lawyer Joshua Kelner.

“While CHS often blames [the Correction Department] for failing to produce people for appointments, when they are continuing to give someone a drug, they have to be accountable for verifying it’s safe.”

William Brown, who died Dec. 15, 2021 from a synthetic cannabis overdose, was on an anti-psychotic drug before his arrest, but didn’t get any medication during his first 12 days at Rikers, the Board of Correction found.

As Herman Diaz choked on an orange peel on March 18, 2022, medical staff did not respond immediately and detainees had to try to render aid before he died, a report by the state attorney general found.

Correctional Health Services disputed any delay in response, a Board of Correction report said.

Mary Yehudah, who died May 18, 2022, of a diabetic seizure, was not screened for diabetes by Correctional Health Services when she entered the jail system, the AG’s office found.

Medication could have reversed the effects of diabetic ketoacidosis and might have saved her, the attorney general found.

In two cases of detainee deaths, Correctional Health Services didn’t know where a detainee was, the reports show.

Correctional Health Services records repeatedly listed Albert Drye as at Rikers when he was already in a hospital, the Board of Correction reported. Correctional Health Services records showed Antonio Bradley refusing treatment at Rikers, when he was brain-dead at Lincoln Hospital in the Bronx.

Health services countered that the Correction Department is responsible for knowing the location of detainees.

In early November, the Correction Department notified the Board of Correction it plans to hire a leading accreditation organization, the National Commission on Correctional Health Care, to review the jail health care system and identify “risks or gaps in oversight.”