The debauchery of Fort Worth’s Hell’s Half Acre took no holidays, not even on Christmas

Hell’s Half-Acre was Fort Worth’s notorious red-light district from the 1870s through World War I, located on the south end of town. It was a gathering place for the worst elements of society, a lawless section of town where decent folks did not venture.

Still, the city had a love-hate relationship with “the Acre” because it was also a cash cow, a mixture of commercial properties and private houses taken over for nefarious purposes. Those houses could be rented for $15 a week and turned into bars, bordellos, and gambling dens. Liquor licenses and public-health certificates were optional.

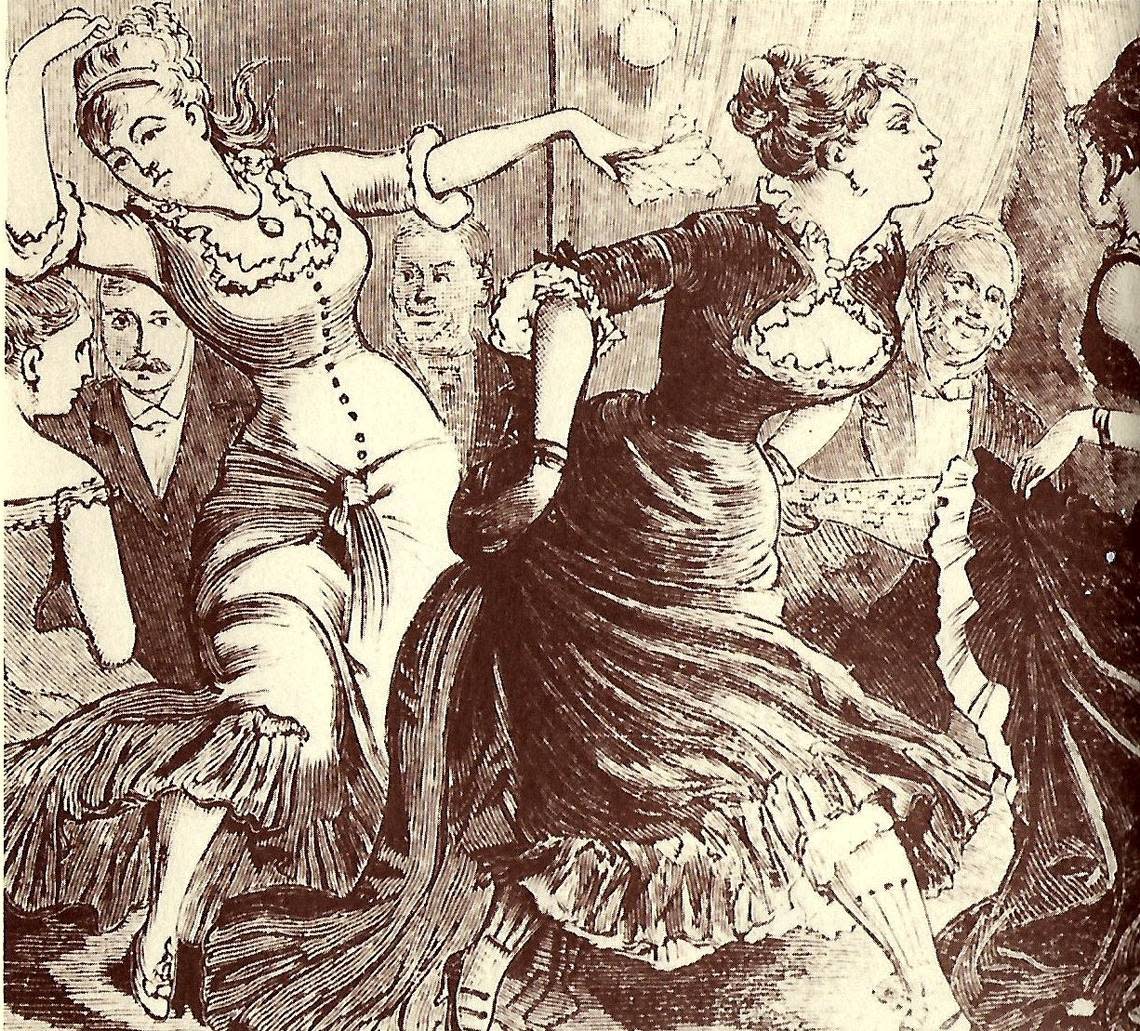

Christmas night 1906 was a typical night in the Acre with one difference: an unidentified reporter for the Fort Worth Record went on a fact-finding tour for a feature story, which would be written in a tone of moral outrage over “the vilest and most abandoned sink hole of iniquity anywhere.”

His tour guide and bodyguard was police Chief of Detectives Al Ray, who claimed to know all the worst haunts and lowest characters in the Acre. The first thing that struck the reporter was the “rows and rows of houses given over to the most depraved and vicious of men and women.” The rest of the evening followed the same script.

Each of the dives they visited — the Standard, the Black Elephant, the Cave — had a story to tell. The Standard was so named because it was supposed to be the gold standard for “vaudeville theater” in the city, but the reporter characterized it as “a den of iniquity” where the shows and the clientele were equally degenerate, made worse by the fact that the proprietor was a woman, Maggie DeBeque. The Black Elephant was a different version of the uptown saloon called the White Elephant because it catered to a Black clientele. The Cave was a hangout for “cripples” when they weren’t working their “con games” on the street.

The reporter was the most derisive of Marion Warren’s unnamed dive, where Black and white people of both sexes were patrons.

It wasn’t just the brazenly immoral behavior on every hand that shocked him; it was the dives themselves where the sheer filth and “nauseating smells” overwhelmed the senses. The smells included clouds of smoke from “foul cigars” that could be purchased at the tobacco stand for an exorbitant 50 cents each. Most saloons had the traditional “free lunch” counter available to any customer who purchased a drink, but in these places the sandwiches were stale and the hands reaching for them unwashed.

Murder, suicide were common

The lowest of the low took their fun in the Acre, where the liquor and the women were both cheap and life was short.

The latest murder had been only a week earlier. And suicide was as common as murder. Among the Acre’s working girls, it was so common as to be hardly newsworthy. A little laudanum laced with morphine made passage to the next world painless and left a peaceful-looking corpse.

The Acre was also home to petty thieves, thugs, holdup men, assassins, and hustlers. Some of them, he noted, actually went by their real names. They were a “hard-faced” lot of men and boys and “repulsive” women.

The reporter concluded that everyone he met was either going to jail or had just gotten out. One of them button-holed Detective Ray to ask nervously, “You ain’t looking for me, are you?” He had only been released from jail that morning.

Any man who walked into one of these joints with a roll of cash had little chance of still having it when he walked out – if he was able to walk out. Many a man was found the next day lying in a back alley either drugged or beaten senseless. Mickey Finns (“knockout drops”) were a standard bar drink in these places. Victims were reluctant to go to the police because they did not want the embarrassing publicity, so they kept quiet.

The Acre rocked all night long, and Christmas night was no exception. Only with the coming of dawn did things slow down but only until darkness fell again. The Acre took no time off for Sundays or holidays. On this Christmas night, no one worried about being home in bed when Santa Claus came. Santa didn’t visit the denizens of the Acre.

The police knew all about the Acre. But for a variety of reasons, they did not shut it down. For one thing, many officers were in the pocket of the vice operators. For another, many of the property owners were respectable citizens with connections at city hall. Instead of arresting people, police were more likely to order the prostitutes and gamblers out of town. That was no problem because the departed’s place was quickly taken by others in the same line of work.

Butch Cassidy, the Sunday Kid and the Wild Bunch likely visited

Even when police made arrests, the jail had a revolving door that let the miscreant right back on the street as soon as they paid a small fine. Occasionally police made a foray into the Acre to retrieve some poor lad seduced by the siren call of illicit thrills and return him to his mother. For “Wanted” felons, the Acre was a good place to hide out because its population was generally anti-authority. In 1901 the Wild Bunch (Butch Cassidy, the Sundance Kid, and friends) came through town and doubtless spent time in the Acre with no one inquiring too closely about the strangers.

All this went on just a few blocks from where respectable folks went to church and lived upright lives.

In a few years, there would be talk in Fort Worth of carving out a “Reservation” where prostitution, gambling, and girly shows could operate openly while strictly segregated from the rest of the town. That proposal in 1909 was narrowly voted down by the city council.

The Record reporter survived his visit to Hell’s Half Acre, and his report took up most of two pages in the newspaper a few days later. He intended his expose to arouse public opinion against the Acre, but in fact newspaper stories like this just made the Acre a more desirable place for the adventurous to visit while advertising its offerings to the more depraved. Young blades who wanted to test their manhood, travelers looking for a little fun away from home, and girls fresh off the farm with big dreams were drawn to it.

The Acre welcomed them all, and on the day after Christmas, it started all over again.

Author-historian Richard Selcer is a Fort Worth native and proud graduate of Paschal High and TCU.