Dec. 3, 1955: A breakthrough in sports and civil rights history

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

John Spratling, chair of the Scarboro 85 Monument Committee, identified the significance of the upcoming 68th anniversary of the first Black athletes being allowed to play basketball in what was previously a segregated school system in Tennessee and the Southeast. John states that this action paved the way for many more Blacks to have opportunities to excel at sports. I believe he is correct and think you will agree as well.

Rose Weaver, who along with Martin McBride initiated an effort to recognize the Scarboro 85 Black individuals who were the first in the Southeast to desegregate public schools on Sept. 6, 1955, when Oak Ridge High School and Robertsville Junior High School were desegregated. Rose and Martin, along with the committee they organized, did this in 2020 to honor the Scarboro 85 on the 65th anniversary of what is becoming recognized as a monumental occasion.

Scarboro 85 information to be taught in Tennessee schools

It was an honor to have served on the Tennessee State Board of Education’s Social Studies Standards Review Committee this year. We included the Scarboro 85 in the standards and expect approval by the state board on second reading in February 2024. This will place the Scarboro 85 story in the standards to be taught in all Tennessee public schools.

Since the initiative led by Rose and Martin, several individuals and groups have helped to recognize the significance of the efforts of those 85 brave young Black students who are advanced in age now. Local newspapers and television stations have helped, as has the city of Oak Ridge and Anderson County, as well as others. Oak Ridge High School's Mark Buckner has engaged the students there to assist in the design of the Scarboro 85 monument being envisioned to be placed on the location of the original pavilion for the Oak Ridge International Friendship Bell.

Rose, with assistance from John and Martin, has written the story of the breakthrough in sports that John identified. Please enjoy the amazing story of individuals who endured things most of us have never had to encounter and still led the way for change, radical change, that today we can now take for granted as normal and expected. It was not so in 1955.

***

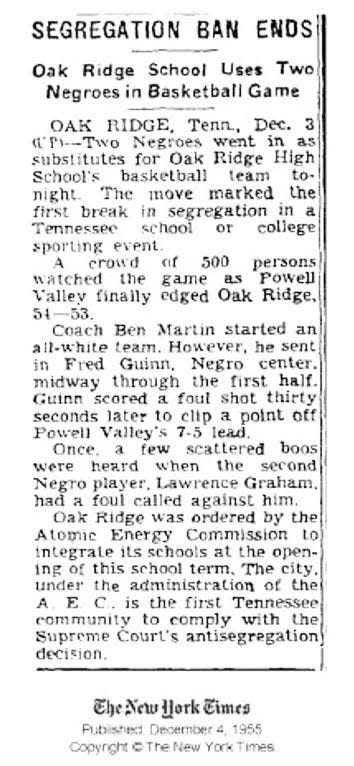

Dec. 3, 1955 is a day that fundamentally changed sports in Tennessee and the nation. That date marks the first time Black student athletes entered an all-white public school (or university) sports event in the Southeastern United States.

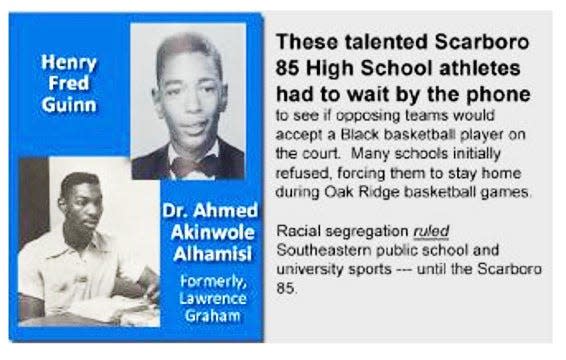

On that day, two young Scarboro 85 students entered an Oak Ridge High School basketball game for the first time, in a game against Powell Valley High School.

It was a major turning point in American civil rights history.

It’s difficult to appreciate the extent of emotional pain these young pioneers experienced. The teams they played were all white … and racial segregation (outside public education) was rigidly-enforced and perfectly legal.

At the outset, some opposing schools refused to play Oak Ridge with a mixed-racial team.

A contemporary New York Times article noted that a crowd of 500 watched as young Fred Guinn and Lawrence Graham (now Dr. Ahmed Akinwole Alhamisi) played in the game where Powell Valley edged Oak Ridge, 53-51. Many felt that more points could have been made if Guinn and Alhamisi had played longer, as they were obviously the better players.

These two young pioneers led the way for future professional superstars, like A’ja Wilson (South Carolina), Candice Parker (Tennessee), Michael Jordan (North Carolina), and Shaquille O’Neal (Louisiana State University). Back in 1955, they would not have been allowed on the court of their respective alma maters due to their skin color. They would not have even been allowed in the universities.

Thanks to the courage and leadership of these Scarboro 85 students, ORHS was able to field a mixed-racial team. This event happened ...

Five years before Ruby Bridges, the first Black child to attend formerly whites-only William Frantz Elementary School in Louisiana.

Two years before the Little Rock 9, who integrated Little Rock Central High in Arkansas. The nine students were prevented from enrolling in the school by the Arkansas governor. They attended only after the intervention of President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

One year before the Clinton 12, the 12 Black students who integrated Clinton High School. Their desegregation efforts were met with protests and violence and on Oct. 5, 1958, the school was bombed.

Three months before Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks gained national prominence in the Montgomery, Alabama bus boycott; and

Six years before the first three Black undergraduates entered the University of Tennessee - and 15 years before the first Black UT basketball player.

In her wonderful book, "Tender Warriors," Dorothy Sterling interviewed the future Dr. Alhamisi. In the book, he recalled: “The phone would ring the day of the big game and coach would let me know the time when the bus would leave for the game and within seconds he would call back and say the opposing team would not play Oak Ridge High if that (n-word) plays.”

“Some teams don’t mind my playing, some teams object, but not the fellas on the team. Mostly it’s the fans or the board of education that decides against us,” said Alhamisi.

In a more-recent interview, Guinn recalled that 60 years ago, calls of of (n-word) go home, darkies cannot play basketball, and other profane language, which challenged their character and worth, were used during games.

In a 1990 interview, Guinn said, “I remember even to this day, a white woman in a red polka-dot dress who was allowed to shout the “n-word” at me throughout an entire game and other white students who threw spitballs on the court anytime me and Lawrence played. When I had an opportunity to play any ball, the shot went in. It did not break my concentration.”

Guinn, now deceased, was a member of the class of 1956.

"It was a terrible thing," he said. "The coach tried to get teams to play us, but they'd say, 'Don't bring the (black) players.'"

"Even at home games, the coach had to get permission from the other teams before (the two black Oak Ridge players) could play," recalled another Scarboro 85 student, Larry Gipson of Oak Ridge.

Alhamisi was an all-around athlete in high school. His brother, Ronnie Graham, who played for the Oak Ridge Bombers baseball team between 1966-1970, recalled that Alhamisi ran into the same situation in high school baseball that he encountered in basketball.

Alhamisi was the catcher for the Oak Ridge Wildcats baseball team, but not afforded the opportunity to use his athletic ability.

“It was his hope − similar to basketball − that he would play more to test his ability and how he measured up to other athletes,” said Ronnie Graham.

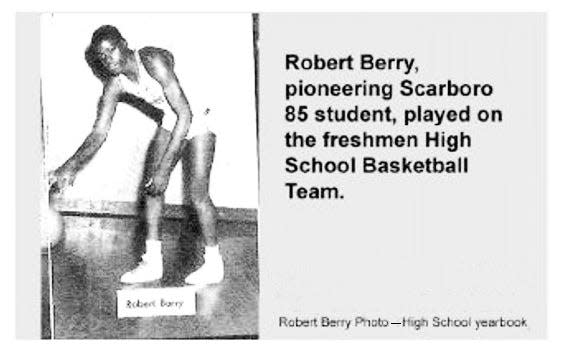

A third game-changing Scarboro 85 basketball player was Robert Berry, who played on the freshmen team at ORHS.

Remember that back then, buses, movie theaters, lunch counters, city and state public facilities, were all segregated. So today, let us think of these three rare individuals. They were courageous leaders, who did not let the shackles of discrimination and difference limit their talent or ingenuity. They believed in the talents they possessed.

Alhamisi is a renowned educator and author. He graduated from the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, where he is retired. Guinn retired from Methodist Medical Center of Oak Ridge and the Y-12 plant.

The Scarboro 85 Monument and Historical Interpretive Site is planned to honor them and the other young Black students who paved the way so we today can embrace the message of racial healing and unity for the nation.

***

Thank you Rose for this reminder of the achievements we all too often have overlooked. Thanks to John for realizing the significance of these three individuals and what they did to break through the segregation barrier in sports.

D. Ray Smith is the city of Oak Ridge historian and his "Historically Speaking" columns appear each week in The Oak Ridger.

This article originally appeared on Oakridger: Dec. 3, 1955: A breakthrough in sports and civil rights history