A decade of hate: How South Dakota's gender-affirming care ban is affecting this family

Editor’s note: This is the third article in a series of six exploring South Dakota’s last decade of anti-LGBTQ+ legislation, “A decade of hate.” Stay with the Argus Leader in the coming days for the fourth, fifth and sixth articles in this series.

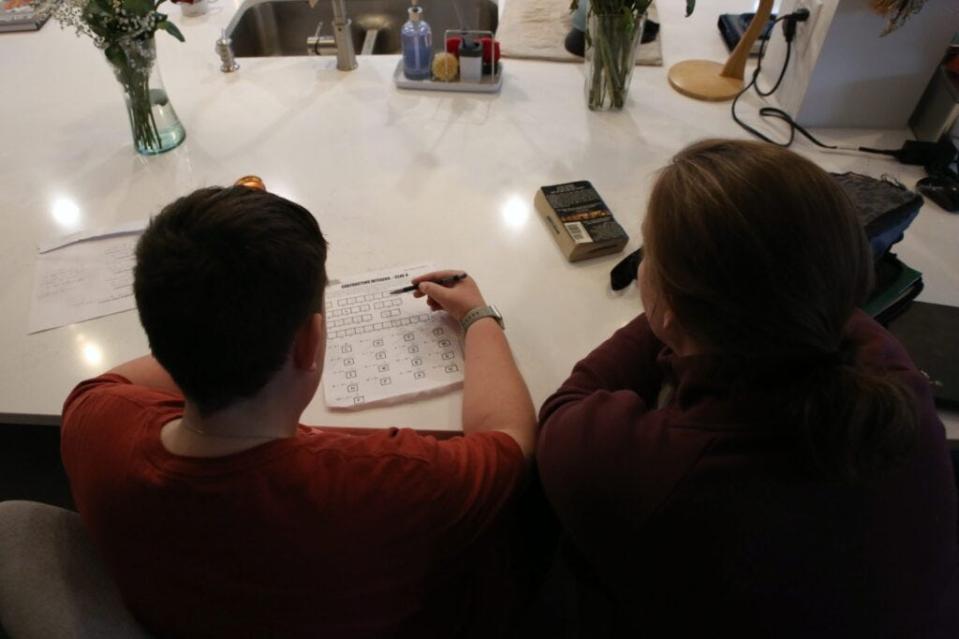

Joey, 12, and his mother, Hannah, are considering leaving the town in eastern South Dakota they’ve called home for more than a decade.

They’re preparing to leave South Dakota because House Bill 1080, which bans gender-affirming health care for minors, took effect July 1, and affects Joey’s ability to get care since he is a trans boy.

Moving out-of-state means uprooting their lives for any one of the few states that have a history and record of protecting LGBTQ+ rights and expanding them. The states they see as options are Minnesota or California, or states in the upper northeast or Pacific Northwest.

More: More than 200 South Dakota bills become law Saturday. Here are the major ones to know.

Joey and Hannah are one of a group of trans individuals and families who have struggled to find medical care, considered leaving the state permanently or seeking medical care across state borders because of HB 1080 and laws like it. Joey and his mother Hannah have requested anonymity for this story because Joey is not publicly out as trans. Hannah also requested anonymity to protect her job and her family’s safety.

Lawmakers “think about this legislation in an abstract way and don’t realize it has such a profound impact on the daily life of these kids,” Hannah said.

What trans medical care looked like for youth in South Dakota

Gender-affirming care is supported by the American Medical Association, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Psychiatric Association, the Endocrine Society and more, and multiple studies have shown it’s associated with better mental health outcomes for the people who seek it.

While HB 1080 bans any form of gender-affirming surgery for minors, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health rarely, if ever, recommends such procedures for minors. Gender-affirming surgery, and even prescriptions to gender-affirming hormone therapy or puberty blockers, require multiple steps be taken and a process be followed before they are advised.

More: A decade of hate: How South Dakota's anti-LGBTQ+ bills have grown in the last 10 years

In South Dakota, providers who were willing to work with patients on gender-affirming care were also few and far between before HB 1080 took effect, according to interviews with healthcare providers and trans people.

Avera Health spokesperson Michelle Pellman said the hospital system didn’t have a history in initiating any type of gender-affirming care to minors.

Sanford Health has held three different summits on gender identity, and some of the trans youth interviewed by the Argus Leader said they’d received gender-affirming care or counseling there. While Sanford Health didn’t make any doctors available to speak on the topic for this article, media relations manager Paul Heinert sent the following statement from the healthcare system:

“Sanford Health is committed to providing exceptional health care for all we serve, including those with gender-related care needs,” the statement said. “Our physicians provide evidence-based medical care in accordance with the applicable state laws where we operate. We encourage patients to talk with their doctor about how we can best support their health care needs.”

More: Gender Identity Summit closed to media, public

Dr. Amy Kelley, who specializes in pediatric and adolescent gynecology at Sanford Health, recently spoke at a trans rights rally in Sioux Falls and shared how anti-trans bills across the country terrify her both as a doctor and as a mother to a trans daughter.

“I think it’s hard for a lot of people in the medical community who feel really strongly about making sure our patients get what they need,” Kelley said. “It’s very hard for us to stay here and want to stay here, but doubly so when you have a child who you really desperately want to protect. I don’t plan on leaving. I plan on staying and fighting. Someone needs to fight for our neighbors, and for all of our LGBTQ+ community.”

More: 'We need to stand up:' Crowd rallies in Sioux Falls to support transgender rights

Dr. Amanda Diehl, with the Community Health Center of the Black Hills, opened the state’s only designated LGBTQ+ clinic, the Iris Clinic, in May 2020 in Rapid City. She usually works with patients ages 9-22 and said she was inspired to open the clinic after she saw a patient and realized doctors don’t always get training on how to best help trans patients. The majority of the work she does involves LGBTQ+ sexual health.

Her clinic has created a space with standards and expected treatment that are gender-affirming from the time someone comes in the door to the time they go to the billing department, she said, noting all the providers are careful to get people’s names and pronouns right.

“I come into the room to see my patients and they’re just crying,” Diehl said. “They haven’t been to a place that’s treated them with respect. Giving people a space to be themselves is just the best part of it.”

Prior to the ban on gender-affirming care for minors, Diehl would connect patients to an endocrinologist and counselor if they needed gender-affirming care.

“People think you can just walk in and get hormones,” Diehl said, dispelling misconceptions about her job. “It’s a specific timeline.”

Before patients can get puberty blockers or hormones, they see a counselor for six months before they receive a letter of recommendation that shows they have an insistent, persistent and consistent gender identity different from what was assigned to them at birth, Diehl explained.

More: Senate committee passes bill limiting gender affirming care, despite opposition from doctors

Consideration is also given to ensure trans patients can afford their care, aren’t at risk of homelessness, are safe and are informed of any risks or permanent changes to come with their treatment, Diehl explained.

But as this law takes effect, Diehl said the impacts to youth who will now have to start detransitioning and going through the wrong puberty will be enormous.

“Despite this being a standard of care, we can’t do this anymore,” she said. “The part I find disheartening is I went to medical school, did residency and seven years of higher education, and they tell me that if I follow the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for gender care, I lose my license. It’s the most disheartening thing I’ve heard for doctors.”

More: Effort to limit gender-affirming care for trans youth in South Dakota moves forward

Other doctors and medical professionals like Diehl testified against HB 1080, including Dr. Nicholas Torbert, a neonatologist at Avera; Dr. Henry Travers, an emeritus pathologist at Avera McKennan Hospital and a clinical professor at the University of South Dakota Sanford School of Medicine; and Anne Dilenschneider, a WPATH-certified gender specialist and mentor at New Idea Counseling in Sioux Falls.

Representatives from the South Dakota State Medical Association, the South Dakota Section of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the South Dakota Academy of Family Physicians also spoke out against HB 1080.

‘There’s a clock on these things’

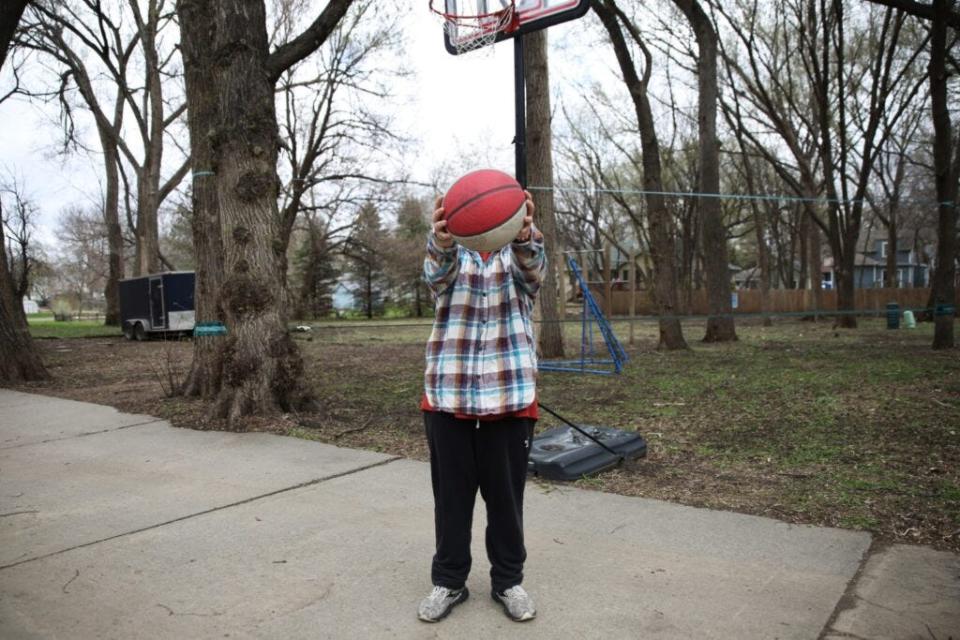

Joey has known he was a boy since he was 4 years old. He began puberty blockers when he was 9.

At that time, it was rare any healthcare provider or pediatric endocrinologist was available, were affirming of trans patients or knew much about gender-affirming care, Hannah said. No one could provide puberty blockers or other forms of care, in her experience.

More: A decade of hate: How trans activists pressured Gov. Dennis Daugaard to veto HB 1008 in 2016

By traveling outside of South Dakota and paying completely out-of-pocket, Hannah was able to get the care her son needed in Kansas City, Missouri, where a team of providers — a social worker, psychologist, pediatric endocrinologist and pediatrician, to name a few — worked together to think about Joey’s needs on a holistic scale.

There, Joey was able to get a puberty blocker implant similar to birth control, but about 90% of Joey’s care has been for his mental health, with regular visits to a therapist and counselor, his mom said. Access to the puberty blocker is important for Joey’s physical wellbeing so he doesn’t experience a puberty that’s in opposition to his gender.

Each visit out-of-state requires time off of work, gas and meals, appointments in the middle of the day or nights in a Kansas City hotel, which can become costly. Spending 10 hours in a car for a doctor’s visit is painful and exhausting, Hannah said, and it means her son misses more school.

Hannah said the family is fortunate to be able to travel for care, and fortunate her workplace is flexible to give time when needed, but she said she realizes that’s not a possibility for other families in South Dakota.

More: 'Children are political targets': A family's struggle with SD's trans health care ban

Families like Joey’s are competing for care in trans refuge states like Minnesota and Colorado, with patients from other states banning gender-affirming care, like North Dakota and Iowa. Waitlists in Minnesota and Colorado are long, and getting an appointment can take anywhere from a year to 18 months, Hannah said.

“When you have a child who is starting to experience puberty, there’s a clock on these things and a timeline in which you need to get care,” Hannah said. “It’s made it much more difficult.”

One of the most challenging things for Joey and Hannah is hearing stereotypes about trans kids and their parents. Hannah said every winter is exhausting because of the arguments they hear about trans people during the legislative session.

“If people knew who we were, the idea that we would indoctrinate our kids into this or force them into something they’re not to score political points or be politically correct is ridiculous,” Hannah said. “Everyone’s doing their best to support their kid as who they are. To listen to who they say they are when they tell us… I can’t imagine fighting them on that.”

It’s frustrating to hear legislators argue about kids like Joey, he said. He wishes his family could stay in South Dakota, and that “they wouldn’t just target us.”

This article originally appeared on Sioux Falls Argus Leader: Why House Bill 1080 has one South Dakota family considering relocation