A decade after Sikh temple shooting, violence remains a real threat for local houses of worship. Here's what they're doing to prevent it.

A decade of mass shootings in Wisconsin | Survivors move forward | White supremacy on the rise | Gun legislation stalls | State's Sikh population grows | Temple’s plans for commemorative event

Ten years ago, when a gunman unleashed terror at the Sikh Temple of Wisconsin, the Jewish community took notice.

At the time, security guards were not commonplace at Jewish institutions in the Milwaukee area, and leaders were reluctant to lock their doors.

But fueled by the Sikh temple shooting, other mass shootings at houses of worship around the country, and the near-constant threats it receives, the Milwaukee Jewish community has spent the last 10 years beefing up its security, training its members and establishing partnerships with police and other faiths.

“We've moved from being very reactive to things to trying to be more proactive and staying a step ahead of the evildoer,” said Ari Friedman, director of security for the Milwaukee Jewish Federation.

Shortly after the shooting, the Federation launched a platform to communicate with every Jewish organization in the state — in real time — about threats. They even developed contingency plans to reach people who, for religious reasons, don’t use electronics on Saturdays.

Today, most facilities in the area are guarded by armed, off-duty law enforcement officers. Doors are locked during services at synagogues.

“At first, we were just getting them to shut the door and have somebody nearby,” said Friedman, who consults on security for over 60 Jewish organizations in Wisconsin. “I can't think of a synagogue that keeps their door unlocked now, 10 years later.”

The Jewish Federation is among the most prepared religious institutions in southeast Wisconsin, largely because Jewish people are often the most targeted faith group. In 2019, 60% of religiously based hate crime victims in the U.S. were Jewish, according to the FBI.

But as the region marks a decade since a shooter entered the Sikh temple, with seven worshippers ultimately dead, experts say other houses of worship are beginning to take steps to secure their facilities and train their congregations.

“There’s a growing awareness among faith communities that they have to be better organized,” said John J. Farmer Jr., director of the Miller Center for Community Protection and Resilience at Rutgers University.

More: Reports of antisemitism in Wisconsin remain near record-high levels in 'troubling trend'

Historically targeted groups are more aware of threat of violence

Nationally, the last decade has seen a spate of mass shootings targeting religious groups and houses of worship, from the attack at a historic Black church in Charleston to the Tree of Life synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh.

Farmer, an expert on security for faith communities, argues that religious institutions need to be prepared for attacks — even if leaders think it’ll never happen to them.

“It has to be a recognition, from the leadership of the community down to the congregants, of the need to take this seriously, and to get over the idea that it can't happen here,” Farmer said. “Because as a consequence of how rapidly information and disinformation and hatred spread, it really can happen anywhere.”

Aug. 4, 6-9 p.m.

Oak Creek City Hall

8040 S. 6th St, Oak Creek

For more information and to register online, visit interfaithconference.org/ticket-info/5 or contact the Rev. J.C. Mitchell at office@Interfaithconference.org or 414-276-9050 ext. 2

In Wisconsin, how concerned clergy and congregants are about threats — and how ready they are for emergencies — varies widely.

Those who have been the targets of hate crimes, such as the Jewish, Muslim and Sikh communities, are generally more cognizant of the possibility of violence at their houses of worship, leaders said.

Among majority-white Christian churches, where threats have been few, there’s a low to medium level of concern, said the Rev. Kerri Parker, director of the Wisconsin Council of Churches.

She said the council, which provides security resources to churches if they ask for them, sees a boost in inquiries after mass shootings happen.

“We find that it really ebbs and flows according to what's going on in the nation,” Parker said. “Especially when an incident happens at a community of faith, I think the concern ramps up a lot.”

Historically Black churches in the area, having seen attacks from white supremacists at other Black churches around the country, tend to be more aware and prepared, said the Rev. J.C. Mitchell, program coordinator for the Interfaith Conference of Greater Milwaukee.

Still, Mitchell has noticed that local Black churches are more focused right now on COVID safety. In general, they’ve been cautious about removing protocols like masks and capacity limits, he said.

Disease control measures — such as asking people to register for services ahead of time, or requiring them to sign in and take their temperatures when they arrive — can create a safer situation overall, Mitchell said.

“It just allows you to interact with them,” he said.

Security experts tout “the power of hello,” or the impact a greeter can make at the entrance to a house of worship by starting a conversation with a suspicious guest. “Acknowledging a risk can deter a potential threat,” a guide from the federal government states.

Threats can crop up without warning, evolve quickly

Religious institutions need to confront the new reality that hateful people can organize and plan attacks through the internet more quickly and easily than ever before, said Farmer, the expert from Rutgers.

“The source of the threats has multiplied,” Farmer said. “There are all kinds of splinter groups, and people can be radicalized over social media without joining a group at all, just by reading things.”

It’s difficult to predict or prevent attacks from a solitary actor with a grievance who hasn’t joined a terror cell or a white supremacist group, for example, he said.

When an organized group does orchestrate an attack, the plans can develop in a matter of hours or days and can overwhelm small police forces and vulnerable religious communities.

After the small Jewish community in the town of Whitefish, Montana, received a barrage of threats and hundreds of armed Neo-Nazis planned to march through the town, Farmer helped leaders develop plans for any future crises. Whitefish is the home of white supremacist Richard Spencer and has only about 10 police officers.

Since hate groups are so well-coordinated, faith communities too should increase their cooperation with police and each other, Farmer said.

“Potentially targeted communities and law enforcement have to be much more alert to the potential for a rapidly evolving threat to overwhelm them,” he said.

The attitude of the would-be attacker has changed as well. From the perspective of the Milwaukee Jewish Federation’s Friedman — who fields reports of antisemitism in Wisconsin weekly — people have felt more emboldened to express their hate publicly in recent years.

“The hoods are off. People that are haters used to hide behind a hood, or hide behind a screen,” he said. “They’re out there plain as day.”

And because of the pandemic, it can be tougher to spot an unfamiliar or suspicious person at a religious service, said Parker of the Council of Churches. Some new members might have been worshiping on Zoom before joining in person, and greeters might not recognize people if they’re wearing masks.

Local leaders note their concern isn’t only an active shooter with the goal to kill as many as possible. Attackers have used arson, bombings and car rammings in recent years at houses of worship across the U.S.

The U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency's "Mitigating attacks on houses of worship security guide"

CISA also offers a step-by-step process for improving security at your house of worship

The Federal Emergency Management Agency lists several resources on its web site

And sometimes, perpetrators of domestic violence go to houses of worship to target their victims.

In an analysis of 37 targeted instances of violence against houses of worship from 2009 to 2019, the federal government found that roughly two-thirds of the perpetrators were “motivated by hatred of a racial or religious identity.” Another 22% were connected to a domestic dispute or personal crisis.

Parker urges churches to be “welcoming and watchful,” and recommends folding active shooter training into broader planning for hazards — from severe weather threats to medical emergencies.

Knowing who the medical personnel in a congregation are, and designating who will help the members who have mobility or cognitive issues, can be useful.

“If people have that ability to not freeze in an emergency, that becomes applicable to a range of emergencies,” Parker said.

Collaboration with police, other faiths is key, experts say

If faith leaders share information about threats they’ve received with other faith groups and with police, it can make a big difference, experts said.

“You never know when a piece of information that one of us has might be the life-saving piece of information that another one of us needs,” Parker said.

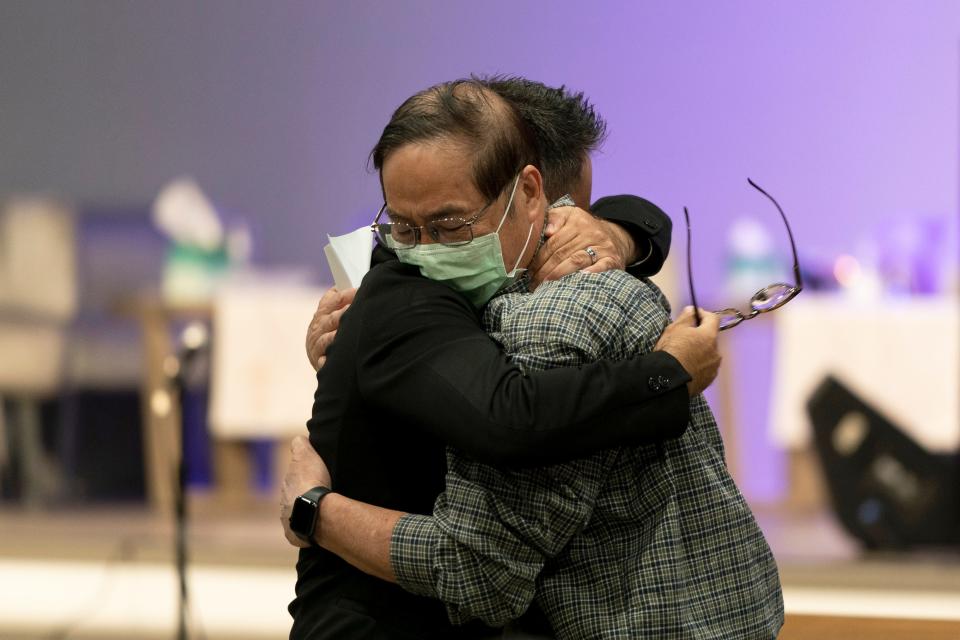

In the 10 years since the Sikh temple shooting, those networks have gotten much stronger in southeast Wisconsin.

The Jewish community’s statewide alert system is one example. Friedman, at the Jewish Federation, also has established partnerships with law enforcement and other faiths.

“I don't want the first time we ever meet to be in front of a bank of microphones,” he recalls an FBI official telling him.

In one successful case of communication Friedman cited, a man entered a Lutheran church and began spouting anti-Christian and antisemitic hate. Leaders at the church told him about it, a testament to the strengthening bonds between faith groups.

Relationships with law enforcement are especially important, Farmer said, because if there is an active shooter, officers would know the layout of the house of worship and the places congregants might be hiding.

“I can't overstate the value of that,” Farmer said. “It really does save lives.” The Milwaukee-area Muslim community also sees the value in working together. Through an informal network of all the Islamic centers in Wisconsin, leaders share threats and reports of suspicious people outside mosques.

The thinking is that if someone is lurking outside one mosque, they might visit others too.

There’s been “good collaboration” between the Islamic Society of Milwaukee and local police captains, said Ahmed Quereshi, past president of the mosque.

On the day of the Sikh temple shooting, Quereshi recalls calling police to ask for a squad car to patrol the area outside the mosque. An officer did arrive — and mosque leaders have continued to report threats they receive to police.

At the Sikh Temple of Wisconsin, there was “no information sharing infrastructure in place” prior to the attack, according to a federal report. But since the shooting, temple leaders have designated a member to report suspicious activity to the other Sikh and Muslim organizations in the area.

'Greater willingness to talk about' security

Sikh leaders have also overseen a massive security upgrade to the Oak Creek temple in recent years.

Reinforced windows are resistant to bullets, and armed guards patrol the building, among other measures temple vice chairman Balhair S. Dulai didn’t want to name publicly.

The community has had to walk the “fine line,” Dulai said, between Sikh values of openness and the necessity for safety.

“You want to welcome everybody, but then again, you want to be cautious, too,” he said.

Dulai is grateful for the federal funding the temple received after the shooting to secure the building. The temple didn’t have the money to make the upgrades on its own, and that’s the case for many other houses of worship, he said.

He supports more federal funding for security measures at houses of worship, saying it’s "step one” to making faith communities safer.

Friedman, at the Jewish Federation, also sees the value in federal dollars. He and his team have been helping Jewish organizations apply for grants from the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

The Department of Justice and several local faith organizations are hosting a forum on protecting places of worship Aug. 4 as part of a series of events marking the 10-year anniversary of the Sikh temple shooting.

It comes at a crucial time — as houses of worship continue to face threats of violence, and as faith leaders are increasingly seeking out ways to secure their buildings.

Compared to 10 years ago, today there’s “a greater willingness to talk about it and think about it,” Parker said.

As less-prepared faith leaders begin to discuss how to keep their congregations safe, they’re often reluctant to do things like lock their doors, hire security guards and add metal detectors. Some feel it conflicts with the welcoming environment they hope to create.

“They all have to strike the right balance for themselves,” Farmer said.

Looking to the future, one thing is certain.

“Mass shootings are going to be a really tragic reality for a long time,” Farmer said. “As a pragmatic matter, people who are in charge of facilities that are potentially vulnerable have to realize that.”

Contact Sophie Carson at (414) 223-5512 or scarson@gannett.com. Follow her on Twitter at @SCarson_News.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Sikh temple shooting raised security concerns for houses of worship