After decades, city and stakeholders ready to tackle E. coli contamination in Vernon River

Holly Pace's backyard is sunken. In a low-lying area of Windsor Forest, the canal behind her house regularly fills and overflows with water, eroding her fence line and bite by bite swallowing chunks of the yard. She's far from the only Savannah resident worried about flooding, but Pace has an extra problem to consider: the water behind her house has more than 20 times the legal limit of E. coli.

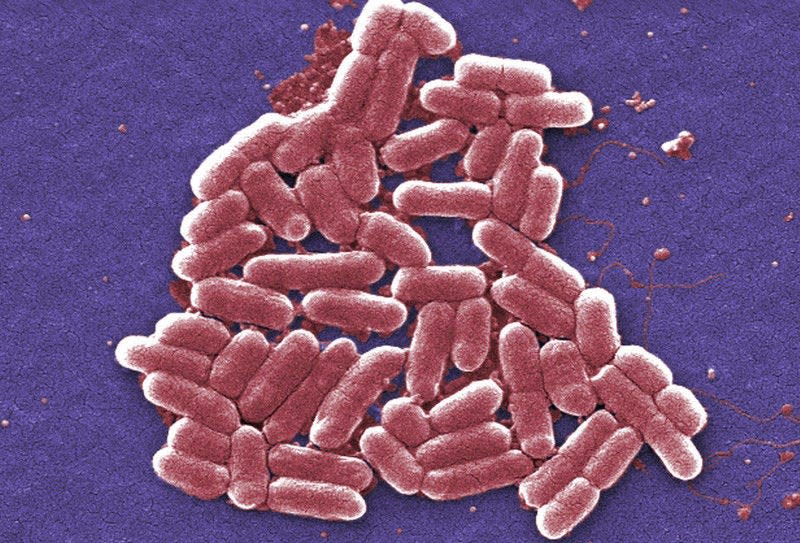

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Division, E. coli is a fecal coliform bacteria that is specific to feces from humans and other warm-blooded animals.

While it may seem obvious that humans don't want to come into contact with feces, the EPA says that E. coli itself isn't likely to be all that harmful to humans who come into contact with it through swimming. However, it is an indicator that the waterway may have other disease-causing bacteria or viruses that live alongside E. coli in human and animal digestive systems.

Common symptoms of exposure to water with high E. coli levels are vomiting and diarrhea.

Casey Canal runs alongside Harry S. Truman Parkway before it connects to the Vernon River, a central line threading the city. But throughout its course, the small waterway is picking up pollution from a spate of sources before it reaches the Vernon River, and along that route is Pace's house behind the LaVida Golf Club.

Her yard stays saturated, Pace said, and she's worried about the health impacts of long term E. coli exposure. When it rains, the skinny canal quickly overflows onto her property. Moreover, the flooding has created mold in areas such her garage, another source of potential environmental health problems.

"We could at least have decent, clean recreational rivers," Pace said. "It's not fair to have that type of quality of water."

She knows that this issue has been long-lived. For her, the flooding started in 2008 with a canal improvement project she claims has caused more flooding in her yard, and even back then the water was known to have high E. coli counts. She's frustrated the situation hasn't seemed to improve much over the years.

"When they tested (the water) about a week ago, the E. coli levels were 2620. (Environmental Protection Agency) standards are 100, or really, zero," Pace said. The numbers Pace refers to are measured in MPN, a statistical estimate of the number of coliform-group organisms per 100 milliliter sample of water.

Her water was tested along with other portions of the waterway by the Ogeechee Riverkeeper, which has been working on an overarching project to clean up the Vernon River.

Ogeechee Riverkeeper Damon Mullis said in mid-2020 his organization launched the Vernon River Project, where "the whole idea was to get all the stakeholders involved and everybody worked together to identify bacterial contamination and sources and try to get it fixed and limit water quality issues."

Related: 'This is my office now': Savannah artists find community, inspiration along Forsyth Park path

More: Savannah restaurant news: Owners of Joe's at the Jepson say hello to new beginnings

According to the Ogeechee Riverkeeper, the Vernon River drains approximately 40% of the city via urban and suburban runoff, all parts of the Ogeechee River watershed. Back in 2001, the Vernon River was declared "impaired" by the Georgia Environmental Protection Division due to contamination, and since then it's been a long and slow battle to track down and remedy the sources.

"Over the 20 years we've had this issue, we haven't really seen an improvement so whatever has been done has been insufficient," Mullis said. His group tests for E. coli as well as Enterococcus, a similar bacteria. Human waste can carry viruses and other harmful bacteria, Mullis said, and so the ongoing pollution is a real health concern — accidentally drinking the water, particularly while swimming, or exposing cuts or sores to the water can have health implications.

But figuring out where the contamination is coming from is half the battle according to Ron Feldner, Savannah's new senior director of Water Resources.

"Our goal is to efficiently convey sanitary sewage to the system and minimize any interaction with that sewage and the environment around the system," Feldner said. "We don't want our manholes overflowing. We don't want our sewer lines leaking. But we have a lot of sewer lines, and we have a lot of manholes."

To make it more challenging, a lot of those systems have years of wear and tear. Feldner said the city "triages" this system as trouble arises, re-lining all the sewer lines at and around leaks to make sure the system is well supported for the coming decades. He said there's been some substantive wins on the river in the past decades, particularly in the 1970s and 1980s with overall stricter water quality regulations and some city system upgrades in the mid-2000s.

But even with this effort, there's other sources of contamination outside of the city's reach, such as lateral lines — those that are on private property, privately owned and connect homeowner's systems to the city's sewage grid. Beyond lateral lines there are leaking septic tanks, and non-point pollution like what runs off of parking lots or feces from livestock or wild animals.

Shawn Rosenquist, a civil engineer in Feldner's department, is also a new hire looking forward to chipping away at the E. coli problem. He's one of the city's representatives working with Mullis and other community stakeholders on a new and improved watershed management plan that is almost complete.

More: First City Progress: Kat-5 Studios breaks ground, 'global production companies' show interest

The plan will have several recommendations for additional things the city can do — ordinances, policies, enforcement — and strategies for working with private property owners. The plan also helps prioritize the most critical areas and highlight the most effective possible solutions.

To better understand where the problem lies, Rosenquist said the city is working with other groups, such as Georgia Southern University, to conduct bacterial tracking to identify what the contaminants are and where exactly they're coming from.

Both Feldner and Rosenquist agree that it'll be many years before the city gets closer to a satisfactory outcome. But, with new staff at the city and a new, collaborative watershed management plan in the works, they're feeling confident that after many years the city is ready to turn a corner and make big improvements in the Casey Canal and Vernon River's water quality.

Marisa Mecke is an environmental journalist. She can be reached at mmecke@gannett.com or by phone at (912) 328-4411.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Savannah strategizes plans to clean E. coli pollution in Vernon River