Decades before Trump's charges, Detroit couple stole treasured National Archives letters

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Charges this week that former president Donald Trump improperly kept and hid top-secret documents that he was required to turn over to the National Archives and Records Administration revived decades-old warnings from archivists about record security.

Until recently, one of the nation's more notorious National Archives cases involved a Detroit couple, who were caught in the early 1960s with a trove of stolen documents that included original signed letters from Presidents John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses Grant, Herbert Hoover and others.

Back then, Wayne State University history professor Philip Mason, who had a hand in identifying and authenticating the stolen one-of-a-kind American history artifacts, warned that treasured records nationwide were at risk and there would be more problems.

Since the Detroit case, National Archives breaches have ranged from the mundane to the most serious: An author who changed a date on a presidential pardon with a fountain pen, a researcher who filched hundreds of World War II-era dog tags, and a former national security adviser who admitted to swiping — and destroying — classified documents.

"The problem of theft has plagued the keepers of irreplaceable records for generations, but there is cause for deep concern today because of the sharp increase in such losses during the past decade," Mason wrote in an academic paper published in 1975. "Moreover, despite the evidence of the upward trend of archival theft, there is little evidence to show that the archival profession has either fully recognized the seriousness of the problem or that the archives are yet taking any concerted preventive action."

Motives for archive thefts, the late professor said, included selling documents for profit, kleptomania, and a "desire to purge the written record of specific data," information that might be embarrassing or politically damaging if they came to light.

The Society of American Archivists, North America's oldest and largest national professional association dedicated to archives and archivists, now has a forum to "combat theft, mutilation, forgery, hacking, and other acts that compromise the integrity of the historical record and deny access to users."

7 suitcases of records

Detroiters Robert Murphy, then 45, and his wife, Elizabeth Murphy, then 31, were arrested in 1963, and indicted on two counts of moving stolen documents taken from various places, including the National Archives, from Cincinnati to Detroit.

That was before the Watergate scandal, which led to President Richard Nixon's resignation and prompted the Presidential Records Act. The law passed in 1978 helped clarify what to do with presidential and vice-presidential records. It mandated that the records be turned over to the National Archives, an independent federal agency.

Trump was arraigned Tuesday on 37 felony counts. Of those, 31 are related to the retention of national defense records. The rest accuse him of conspiracy, obstruction, and making false statements. If convicted, he could be sentenced to substantial time in prison.

The Detroit case, however, was far less complicated and was related to stealing presidential records to resell them, not keeping them.

More: First-class stamp prices to jump 3 cents: Stock up on Forever stamps

More: Michigan deer goes for long swim in Straits of Mackinac, stunning onlookers

Robert Murphy, who was born Samuel Matz in Cleveland, adopted many aliases and identities to pilfer precious documents from the National Archives and other repositories and libraries throughout the 1950s and '60s, according to news accounts.

At various times, Murphy posed as a researcher, historian, and journalist.

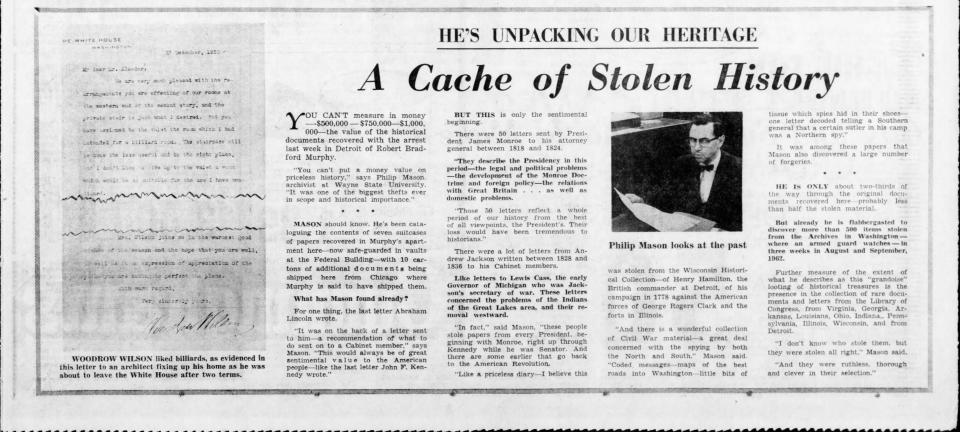

A Free Press report, "Cache of Stolen History," published on Jan. 12, 1964, said authorities found seven suitcases of documents in Murphy's Detroit apartment. Mason called the heist, "one of the biggest thefts ever in scope and historical importance."

Among the artifacts: The last letter President Abraham Lincoln wrote; 50 letters sent by President James Monroe, including the development of the Monroe Doctrine; and letters President Andrew Jackson wrote on topics related to the American Indians and the Great Lakes.

The cache also included Revolutionary and Civil War documents and coded messages sent during those periods. And, among other things, documents connected to Lewis Cass, Governor of the Michigan Territory, and later a Secretary of War, a U.S. Senator, and even a presidential candidate.

The Murphys were convicted and each sentenced to 10 years in federal prison.

A warning and precedent

Nearly four decades later, a former high-level official got caught stealing classified records from the National Archives, possibly to study or attempt to obscure the records.

Sandy Berger, a former National Security Adviser to President Bill Clinton, pleaded guilty in 2005 to taking and destroying documents from the National Archives two years earlier. The documents were reportedly connected to terror threats made prior to the 9/11 attacks.

Initially, Berger claimed he had made an "honest mistake."

But he later pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge as the news media reported he had visited the National Archives multiple times, hid records in his clothing, placed them under a construction trailer to retrieve later, and cut copies up with scissors.

Berger — who former President Barack Obama called "one of our nation’s foremost national security leaders" — was sentenced to 100 hours of community service and probation and a $50,000 fine. He lost his security clearance and gave up his license to practice law.

When Berger died in 2021, the first paragraph of his Washington Post obituary said he "helped shape foreign policy" but also included the controversy of "his unauthorized removal and destruction of classified documents from the National Archives."

His New York Times obit said the records theft made him "politically radioactive."

It's unclear how much the records charges against Trump will affect support for his presidential campaign or how much he cares about what his obituary will say. Before Trump was voted out of office, he was impeached twice. Since his term ended, he has been indicted twice.

Mason, who was the founding director of the Walter P. Reuther Library of Labor and Urban Affairs on the campus of Wayne State University, also had been president of the board of the Historical Society of Michigan and President of the Society of American Archivists.

The professor died in 2021, but had suggested in "Archival Security: New Solutions to an Old Problem" that part of the challenge with securing documents was that archivists were reluctant to publicize the theft and destruction of them. Generally, he said, such misdeeds came to light through the news media's reporting.

And, Mason concluded, there was "ample evidence" achieve security would continue to be a problem. He also cautioned there was a "whole generation of researchers who equate archival and library rules with a form of authoritarianism and who have few qualms about bypassing and subverting" them.

He did not mention — or perhaps imagine — a former president might be accused of being in that group.

Contact Frank Witsil: 313-222-5022 or fwitsil@freepress.com.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Decades before Trump, feds prosecuted Detroit couple in records case