Into the deep legacy of Memphis’ African American medical community | Norment

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In January, Memphis lost two African American medical giants.

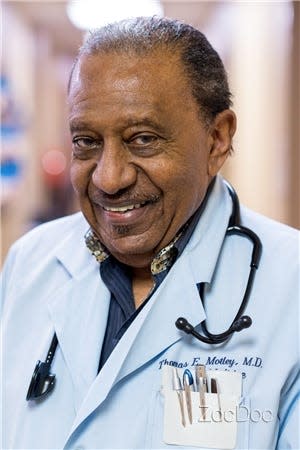

Dr. Charles Champion, a pharmacist, truly was a champion for his profession and the Black community. The same can be said for Dr. Thomas E. Motley Sr., a well-known and respected internal medicine physician. Both served their communities, broke racial barriers, and were the epitome of champions, for they were defenders, supporters, advocates and guardians for the community they loved and served.

Both died just weeks before Black History Month, but their legacies will stand strong. And each has offspring following in his footsteps. Dr. Motley’s son, Todd Motley, M.D., is also a Memphis internist with a thriving practice.

Dr. Champion was proprietor of Champion’s Pharmacy and Herb Store in Whitehaven. His pharmacist daughters, Dr. Carol “Cookie” Champion and Dr. Charita Champion, will continue to operate the family business, along with their mother, Carolyn, co-founder and office manager, and niece, Jessica Champion, a pharmacist technician who is business manager.

In a world where family-owned pharmacies are rare, having been overtaken by mega-chain drugstores, Champion’s is a fixture in Whitehaven. It is known for its herbal remedies, which the late Dr. Champion perfected over the years. He was 92 when he died.

Born in 1930 at John Gaston City Hospital in Memphis, Champion partly grew up in Greenfield, Tenn., on his grandparents’ farm and attended Tennessee A&I State University in Nashville. He transferred to Xavier University in New Orleans to study pharmacy because Tennessee schools were strictly segregated; the state paid for his studies out of state.

After graduating from pharmacy school in 1955, Champion served as a U.S. Army pharmacist in Germany. He then returned to Memphis and became the first African American to work as a pharmacist for a city hospital with a job at John Gaston Hospital. Still, because of segregation, Champion could not eat in the dining facilities at John Gaston.

He later became the first Black retail pharmacist in Memphis, and in 1981 opened his own pharmacy on Third Street before moving to his Whitehaven location.

About 10 years younger than Dr. Champion, Dr. Thomas Motley was born in Whiteville, Tenn., about an hour’s drive from Memphis. Growing up in nearby Bolivar, my family and the Motley family knew each other well. My uncle and Dr. Motley’s father, Robert E. Motley, owned the Motley and Rivers Home in Whiteville. An aunt and uncle were best friends with Dr. Motley and his first wife.

At Howard University in Washington, D.C., Dr. Motley earned a BS degree and then his medical degree from Howard University College of Medicine. After serving in the U.S. Navy, he returned to Memphis, went into private practice, and became the city’s first African American internal medicine physician.

Over the years, Dr. Motley served as medical director for both cardiac rehabilitation and the department of preventive medicine at Methodist Healthcare Systems. He also served as chief of staff for Methodist Extended Care Hospital and was a founding partner of the Eastmoreland Internal Medicine Group. He also was consulting physician for St. Francis Hospital and Baptist Memorial Hospital. Methodist purchased Motley’s Eastmoreland practice in 2013; Dr. Motley retired in 2020.

Dr. Todd Motley says his father was dedicated to family and community. “My father’s highest priorities were service and education,” he says. “Because he was one of the first Black doctors in the city, he was a great influence on the next generation. That’s always understated.”

Sign up for Latino Tennessee Voices newsletter:Read compelling stories for and with the Latino community in Tennessee.

Sign up for Black Tennessee Voices newsletter:Read compelling columns by Black writers from across Tennessee.

Champion and Motley endured challenges to become doctors

We should keep in mind that Dr. Champion and Dr. Motley overcame numerous obstacles to earn their degrees and establish their practices so they could serve the Black community. And at a time when Black Memphians had to settle for substandard care because of racism and segregation.

Yet, there were Blacks making waves and history in the medical field even before Dr. Champion and Dr. Motley. In 1837, Dr. James McCune Smith graduated from the University of Glasgow in Scotland, becoming the first African American to earn a medical degree. Ten years later, in 1847, Dr. David Jones Peck became the first Black student to graduate from a U.S. medical school (Rush Medical College in Chicago).

As early as 1852, the Jackson Street Hospital was established in Augusta, Ga., as the first facility of record solely to care for Black patients. A decade later, in 1862, Freedmen’s Hospital was established in Washington, D.C., as the nation’s only federally funded health care facility for Blacks. In 1891, in Chicago Dr. Daniel Hale Williams established Provident Hospital and Training School for Nurses, the first Black-owned and first interracial hospital in the U.S. (Two years later, the legendary Dr. Williams performed the first successful operation on a human heart.)

In Memphis, the Collins Chapel Connectional Hospital was founded in 1910 by the Collins Chapel Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, the oldest CME church in the city. In 2021, the Collins Chapel hospital facility that was built in 1954 was reopened after being renovated by the 180 churches of the First Episcopal District (Tennessee and Arkansas). The historic African American hospital partnered with Room In The Inn Homeless Ministry and now serves the homeless community of Memphis and Shelby County.

Memphis’ African American medical legacy also is carried forward by the Bluff City Medical Society, which was established by Dr. Miles V. Lynk in the early 1900s to support Black doctors. Dr. Clara Brawner, the first Black woman to practice medicine in Memphis, often held the Society’s meetings at her home in North Memphis when she was president in the mid-1950s.

Before founding Bluff City Medical Society, Dr. Lynk was among the 12 Black doctors who established the National Medical Association in 1895 in Atlanta. He also was the organization’s founding vice president. Doctors were barred from other medical organizations. It wasn’t until 100 years later, in 1995, that Dr. Lonnie Bristow would become the first African American president of the American Medical Association.

Hear more Tennessee voices:Get the weekly opinion newsletter for insightful and thought-provoking columns.

Continuing the legacy

Over the decades, other notable Black doctors made their mark in the medical profession. Among them were Dr. Charles R. Drew, who in 1940 presented his thesis, “Banked Blood,” in New York, which included his discovery that plasma could replace whole blood transfusions; in 1946, African Americans were among the medics that landed in Normandy on D-Day; and Dr. Louis W. Sullivan became the founding dean and president of Morehouse School of Medicine in 1975 and served as U.S. Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services during the George H.W. Bush Administration.

In 1981, Dr. Alexa Canady became the first Black female neurosurgeon in the U.S.; Dr. Patricia Bath in 1988 became the first Black woman physician to receive a medical patent (Laserphaco Probe for cataract treatment); Dr. Mae C. Jemison became the first Black woman in space in 1992; and Dr. Joycelyn Elders became the first African American to be appointed as U.S. Surgeon General in 1993.

The medical professionals mentioned here are just a sampling of the enormous talent and contributions that African Americans have made to medicine and therefore to humanity. Keep in mind that while choosing noble professions that greatly benefited their communities, these doctors had to diligently work through racism, segregation, skepticism and other challenges. Yet they prevailed.

Lynn Norment, a columnist for The Commercial Appeal, is a former editor for Ebony Magazine.

This article originally appeared on Memphis Commercial Appeal: Norment: Memphis’ African American medical legacy stands proud