Deep in storage in Kansas City’s Black Archives: Ku Klux Klan robes. Here’s why

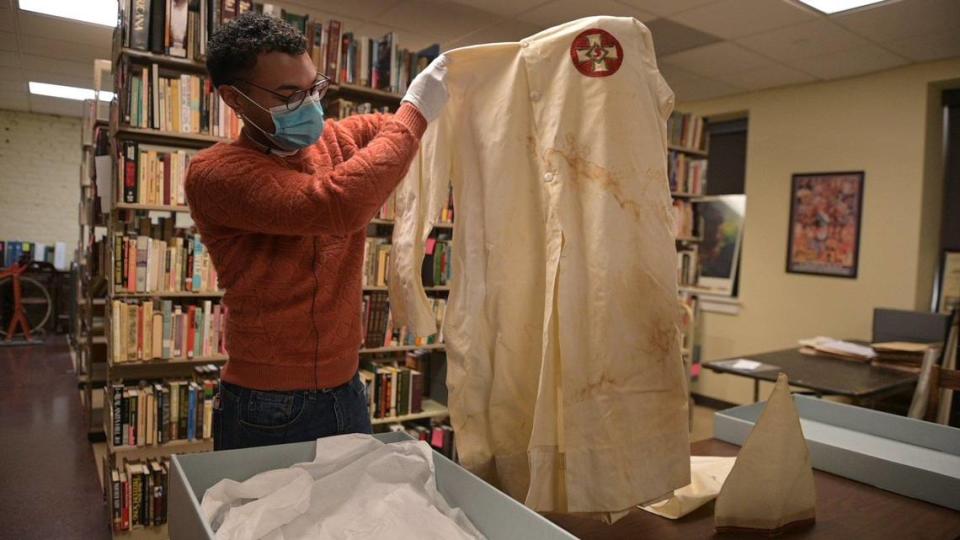

In the back storage area of the Black Archives of Mid-America, among rows of shelves, sits a box containing a chilling and eerie sight to behold: a set of Ku Klux Klan robes, complete with a pointy hood.

“We do not put that robe on display,” says Carmaletta Williams, the archives’ CEO. “If someone wants to see it, we will show it to them.”

Though the Klan emblem itself is kept out of site, the museum does not hide that bit of history in its messages, she said. “We must include (the Klan) when we talk about our history and the creation of a strong Black community,” she says.

While Black History Month is a time to celebrate achievements, it is also necessary to remember the dark and uncomfortable pieces that make up Black history.

The Black Archives stands as one of the only Kansas City institutions dedicated to preserving, if not always showcasing, the long road traveled toward freedom and equality.

The robes have been exhibited only once. They and just one other item in the collection, an O.J. Simpson jersey, are kept in permanent storage.

Williams, who has spent over two decades teaching African American studies, sees a need to preserve all aspects of history while at the same time not glorifying or promoting the negative aspects.

The robes, made of a coarse fabric that was white at one time, are now more gray and covered in dark rust-colored stains. Blood? No one knows.

Nic Gibson, who has worked with the Black Archives since October, still feels uneasy about them.

“I never thought to myself that one day I would be holding a KKK robe,” says Gibson, who came to KC from his hometown of Philadelphia to work with the Black Archives for a year. “I have only been here for just a few months, but I really like it. It has been great. There is a lot of rich local history I was just not aware of coming from the East Coast. There are so many interesting people to come from this area.”

The museum started in 1974 in the trunk of founder Horace M. Peterson III’s car. It expanded into an old YMCA building and eventually into its current location at 1722 E. 17th Terrace. It now owns numerous historically significant items donated and used to educate people on the evolution of the culture.

Gibson, who is helping to digitize its catalog, spends most of his time logging and processing donated items into the database. He thinks preserving items like the Klan robes is an important part of being a custodian of history.

“The KKK and Black history are incredibly intertwined. To pretend like it didn’t exist and not preserve it just seems like a crime against history, to be dramatic a little bit,” he says.

The stories of how the Klan robes made their way into the collection are the stuff of urban legend.

All that is known for sure is that they arrived in the late ’80s to early ‘90s, obtained by Peterson before his death. They still embody the terror and harassment Black people across the South and, yes, the Midwest endured.

Missouri was a slave state, and for a time, Black people were enslaved in Kansas as well. After the Civil War, the Klan reemerged in the 1920s, subjecting Black Missourians to intimidation and physical harm.

The Black Archives’ Room of Remembrance pays tribute to 63 victims who died by lynchings. A mural on the back wall hauntingly portrays one such lynching. Wooden blocks list names of the victims and the locations of their deaths. Some are accompanied by a jar of soil from the sites of the lynching.

“There was no protection for us against people in the Klan or who had Klan mentality, so the Black folks had to band together. One of our focuses and mantras is that we don’t make revisionist history. We don’t want to clean up the history or make it more palatable,” says Williams, a Kansas City native who has worked with the archives for the past four years.

In recent years, she has felt the need for the archives even more with the debates over critical race theory and moves to curtail or even ban Black studies in schools.

“We have the only site outside of Montgomery, Alabama, dedicated to the people who were victims of racial murders and lynched. We don’t just focus on the people who were victims. We also focus on the people who were victors, those people who overcame racial injustice. We tell the truth and how it really was,” she says.

The Black Archives is also home to the Kauffman Exhibit Hall, a permanent exhibit showcasing prominent Black local figures. Adjacent to the Room of Remembrance is Lucy’s Cabin, where the once enslaved Lucy A. Willis lived and and then stayed with her daughter after she was freed.

On Feb. 18, the Black Archives will host a Black History Month luncheon with keynote speaker Academy Award-winning filmmaker Kevin Willmott. The event is sold out.

Williams hopes more people will use the services of the Black Archives and, in time, see it on all local schools’ yearly field trip lists.

“People need to come and visit the archives and see the exhibitions. We have many classes that come and learn here, but we need to see more,” Williams says. “Some people want to protect their children from the past, but you have to tell them the truth.”