Defying gentrification: Carrboro home built by freed slaves in 1879 remains in family

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

For most of her life, 89-year-old Dolores Hogan Clark has lived in the two-story white farmhouse built by her great-grandparents at 109 Jones Ferry Road, just on the edge of Carrboro’s downtown.

Both former slaves, Toney and Nellie Strayhorn were among the first Black families to settle in town. In 1879, fourteen years after slavery ended, they purchased 30 acres for an unknown sum, clearing the forest land to build a one-room log cabin and farm.

“They ate, slept, bathed — did everything in this room,” Dolores Clark recalls, sitting in the original 150-square-foot space she now calls her “fancy room,” hosting visitors on a set of antique tufted Victorian-style chairs. Gold-framed portraits of her ancestors hang on the wall.

“Nellie even died here,” she adds, pointing to the exact spot where the matriarch’s bed once stood. “She was 100 years old and 30 days. She wasn’t even sick. She just passed away in her sleep.”

For almost 150 years, some member of Dolores Clark’s family has lived in the 1,876-square-foot home, under its tin roof, adding extensions — “first up, then out” — to meet their growing needs. Called the Strayhorn house by locals, it survived the racial violence of the Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras. Later, it defied the tear-down trend that displaced other Black families as land values soared. (Once a blue-collar town, Carrboro is now one of the most coveted ZIP codes in the Triangle. The median priced house is $688,000, up 60% year-over-year, according to Redfin.)

After multiple restorations, the house is a patchwork of rooms and porches on a half-acre lot where Dolores Clark lives with her grandson, just a block from CommunityWorx and Dragonhide Tattoo. Nellie’s hand-carved oak bed remains but has been relocated to the adjoining primary bedroom.

The house is also a historic landmark.

A lasting legacy

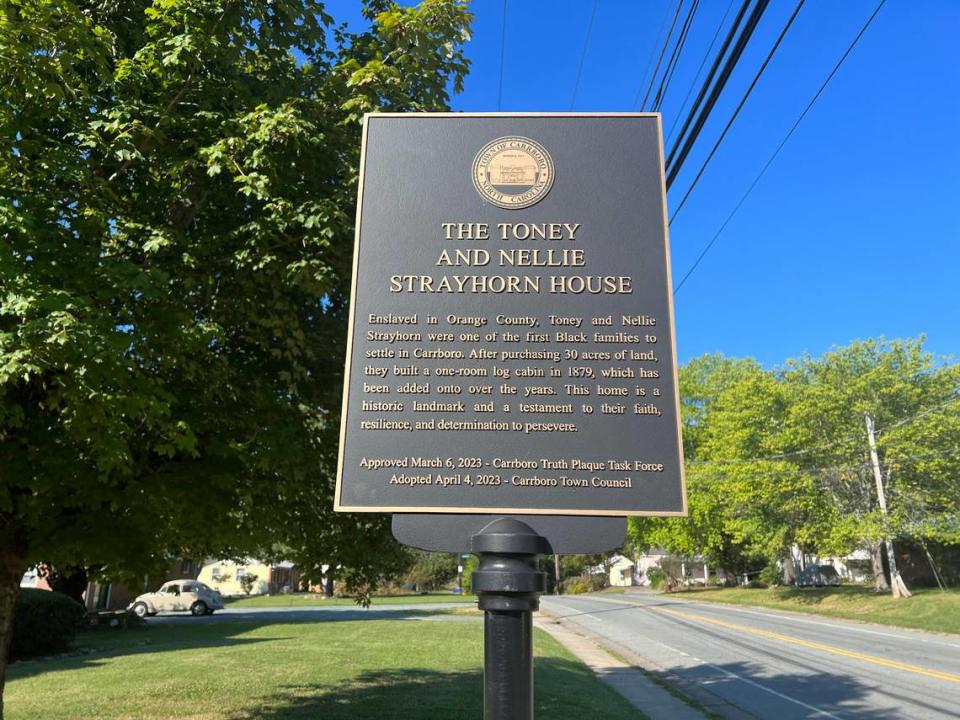

Carrboro leaders recently recognized the house with a “truth plaque” as part of an ongoing campaign launched in 2019 to recover more of the town’s rich Black history. Embossed in brass letters is a 59-word statement acknowledging the family’s “faith, resilience, and determination to persevere” in a town that is only now starting to reconcile its racist past.

Its namesake, Julian S. Carr, was a Durham industrialist and white supremacist.

The first truth plaque is in Carrboro Town Hall. The second is at the site of the former Freedman School next to St. Paul’s AME Church at 101 N. Merritt Mill Road.

The third now stands in Clark’s front yard.

More than 100 people came to the house for the unveiling ceremony, with Strayhorn descendants spilling out into the yard, gathering under the old mulberry tree that’s provided shade for so many generations.

“My great grandfather was a visionary,” Dolores Clark says. Even then, as a Black man, he understood the value of land for creating generational wealth. “It’s a testament to our family and legacy.”

A storied past

Toney Jinkins Strayhorn was born in 1850, an enslaved child in Orange County. Working on the 178-acre Gilbert Strayhorn plantation near Hillsborough, he was just 7 when his mother was sold on the auction block. He never saw her again.

Freed in 1865, he later ventured off the plantation, taking the last name of his slaveholder. With the nation’s oldest state university nearby in Chapel Hill, he worked as a master brick mason, building homes and the church that became the Carrboro Century Center.

In 1876, he married Nellie Stroud, also a former slave. She had worked in a law office for $5 a month and grew up at the Wesley Atwater plantation west of Chapel Hill.

Together, they pooled their savings, scrimping until they had enough money to buy land.

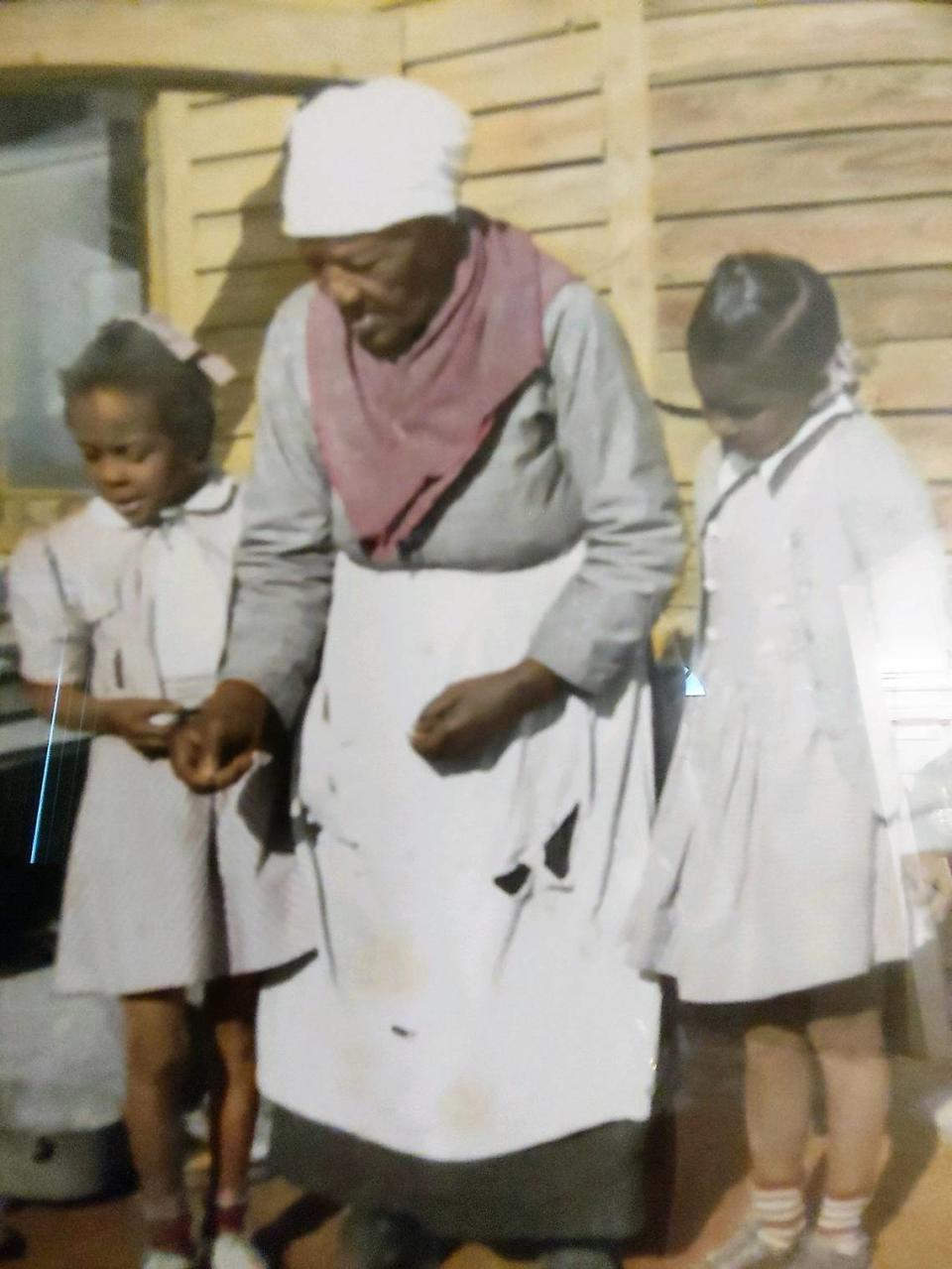

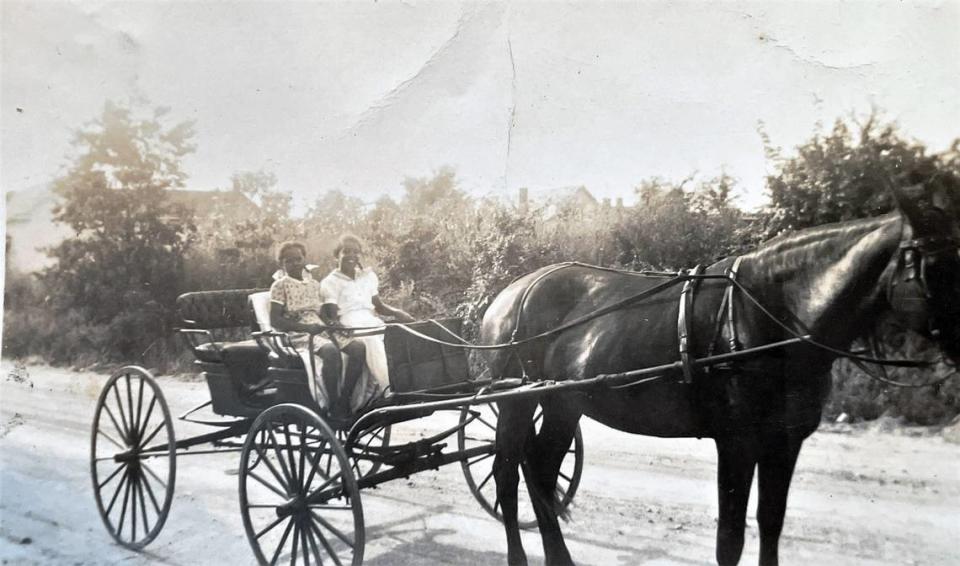

“The Strayhorns worked the fields,” Dolores Clark recounts, selling vegetables, milk, butter and cotton in town to earn extra money. “We had cows, chickens, hogs and horses. Nothing was purchased from the store, except flour, sugar and maybe coffee.”

They became pillars of the community. Toney learned to read on the porch by moonlight to avoid attracting the attention of the Ku Klux Klan. He also became a minister and a magistrate. He helped found the county’s first Black church — now First Baptist Church in Chapel Hill.

Nellie was a community advocate and the matriarch to the extended family. The family shared their stories in a 2021 video interview as part of an oral history project produced by St. Thomas More Church.

They had two children, William and Sallie Strayhorn. When both children died early, along with Sallie’s husband, Fred Barbee, they became the primary caregivers to nine grandchildren, from toddlers to teenagers.

“Toney said, ‘I will raise them even if I have to live on bread and water,” according to family lore.

And that’s what they did.

A black-and-white photo of the family from the early 1900s sits on the mantel. Toney is posing outside on his front porch, staring into the camera, wearing a black bowler hat and bow tie. Nellie stands upright, her shoulders back, hair in a bun, a child at each side.

Over the years, they formed their own family compound — a block of houses at one point totaling eight cottages — eventually divvying up the land to descendants. Toney’s son William built 107 Jones Ferry Road in 1919.

Toney died at age 84 in 1934, a year after Dolores Clark was born. Clark grew up in the main house, raised by Nellie and her mother, Annie Ruth Stroud.

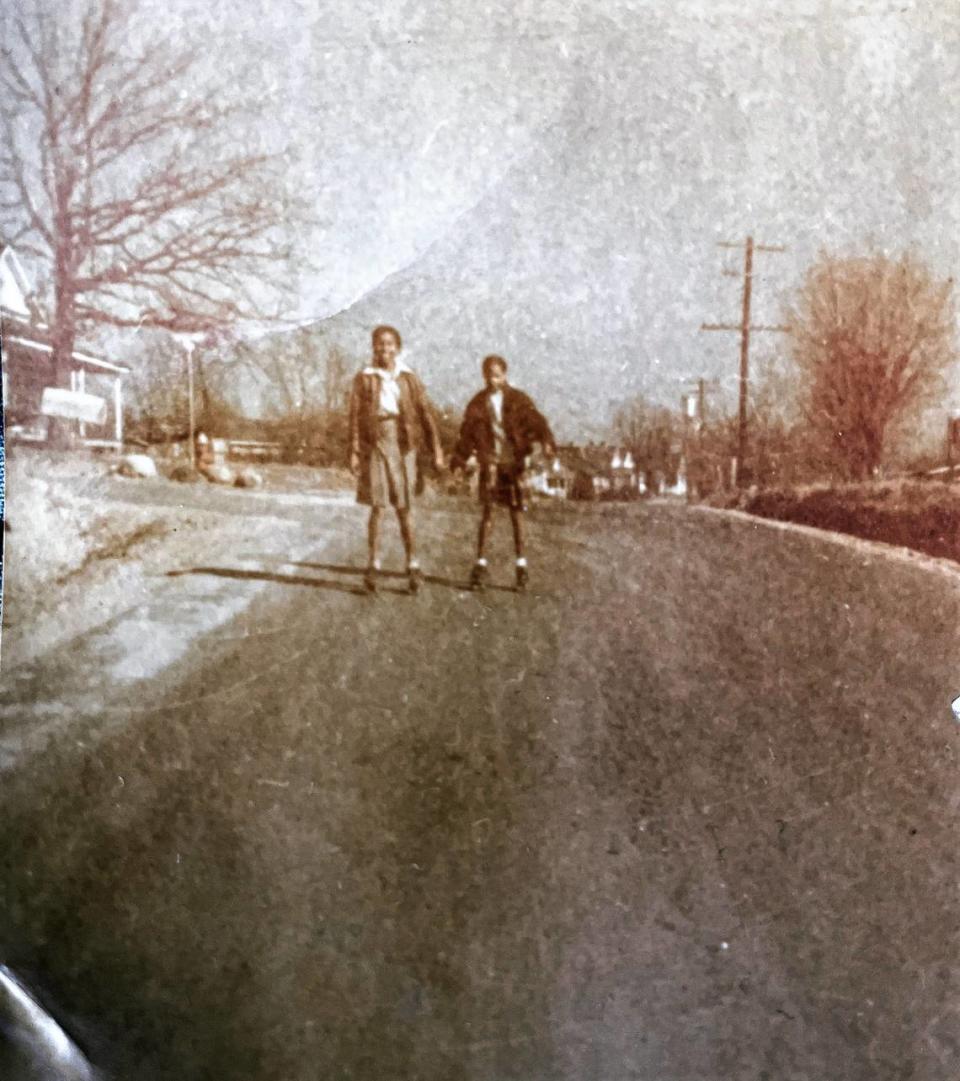

Her cousin, Georgia McCoy Bradsher, lived next door. The girls spent many hours helping with farm chores, roller skating on Jones Ferry Road and playing ball in the yard.

Defying gentrification

For a time, Carrboro had a thriving Black community, says Dolores Clark’s daughter, Lorie Clark, who lives next door. It’s the only other house that remains in the family. Bradsher, now 90, now lives in Burlington.

Black-owned businesses once lined North Graham and Franklin Streets. But that’s not the case anymore.

“Gentrification,” says Lorie Clark, who works in the Chapel Hill-Carrboro City School system as a restorative justice advocate. “The increased taxes and developers pushed people out. If you didn’t know that coming here, and just looking around, you’d think that the Black community is almost nonexistent.”

On this afternoon, she’s joined her mother to swap stories and plan the next phase of work to preserve their Carrboro homeplace. A scrapbook on the table holds faded newspaper clippings, old deeds, tax receipts, one of them dating back to 1906.

“I was just looking at one yesterday,” Dolores Clark exclaims. “It was $6 for property tax. Six dollars!”

Together, they’re working to get the home on the National Register of Historic Places. And with the help of the Chapel Hill Preservation Society, they’ve secured grants totaling more than $100,000 over the years, funneling resources into preserving the integrity and structure of the home.

Workers recently uncovered Toney’s masonry work while restoring the foundation. “When they took up the floor, I could actually see the stacked stone,” Lorie Clark says.

They get calls and letters in the mail asking to sell. “But I never will,” Dolores Clark says. “That’s the way (the Strayhorns) wanted it. To keep it in the family. This is all that we have.”