‘Deja vu’: The Nikole Hannah-Jones tenure controversy rings familiar for some at UNC

In the middle of a sweltering Chapel Hill summer, UNC’s Board of Trustees finally came to a conclusion.

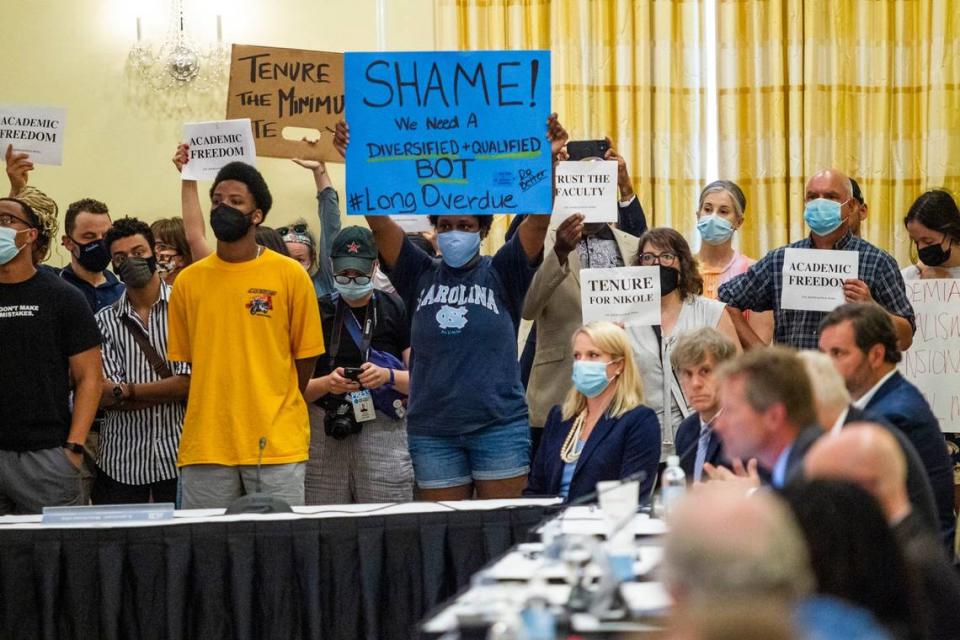

A saga of student protests and intense local and national press culminated in two hours of discussion behind a closed door and a sudden public vote.

The decision? UNC would at last have a freestanding Black Cultural Center.

Now, 30 years later, history repeats itself, some campus observers say, with trustees once more being pressured into action on matters of race, albeit with a different outcome this time.

Nikole Hannah-Jones’ July 6 decision to take a position at Howard University and decline UNC-Chapel Hill’s delayed offer of tenure followed pressure from student and faculty leaders, legal threats and the departure of other Black faculty.

While the controversy pushed racial tension to the fore, many — including Hannah-Jones — have said the issues that define her case are not new to the university.

‘We have always fought’

UNC, a university built by enslaved people in the late 1700s, is a predominantly white institution. Of its 4,000 full-time faculty members, 226 are Black.

“We have always fought for Black faculty and staff,” said Angela Bryant, a former N.C. state senator and two-time UNC graduate. “There’s never been enough or fair representation of Black faculty and staff at the university.”

Bryant, who attended UNC in the early 1970s, was often the only Black person in her classes. She later served on the UNC Board of Trustees from 1991 to 1999 and the systemwide Board of Governors from 1999 to 2003, putting her in a unique position of having once been both a student activist and system official.

During the fight for the Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History in the 1990s, Bryant was one of two Black members on UNC’s Board of Trustees. Students played a large role in persuading the university to establish a freestanding center, waging years of protests and a sit-in at the chancellor’s office that ended in 16 arrests.

UNC has had a reputation that attracts “justice seekers,” which can lead to frustration, Bryant said.

“When you bump up against the glass ceiling or the cement wall against justice and equity, then it becomes very disappointing. People get angry about it,” she said. “It doesn’t have to be that way.”

Roger Perry, who chaired the Board of Trustees from 2007-09, said students and faculty can wield great impact when advocating for racial equity at the university.

“Carolina has always been a melting pot, and it’s always been stirred considering the issues of the times,” Perry said.

The university’s governance has become more politicized, Perry said. In his time on the board, vetting a candidate for tenure beyond the recommendation from faculty and administrators was not the board’s role, he said.

“When volunteer governance boards, like the Board of Trustees, get down too far in the weeds and want to meddle in things that ought to be left up, in this particular case, to the faculty and the administration, and then you overlay that with how political times are and how political things have become ... then you get the kind of situation that we found ourselves in, or the University found itself in,” Perry said.

James Moeser, the ninth chancellor at UNC and retired professor in the Department of Music, said the fact that Hannah-Jones will not be teaching at the university is a tragedy. He also expressed sympathy for Chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz and Provost Bob Blouin.

“I also understand the difficulties that they have leading the university in this political environment,” Moeser said.

The tenure of former Chancellor Carol Folt, now president of the University of Southern California, concluded in the controversy surrounding Silent Sam.

In 2019, after activists had pulled down the Confederate statue, she ordered the removal of its base. In the same announcement, she said she would be resigning from the university. Her departure date was later moved up several months by the UNC Board of Governors.

“The chancellor is limited by the political forces that are basically in charge of governance of this university and the university system, which are very resistant to change,” Moeser said.

‘It is exhausting’

In some cases, when pressure has not been enough, students and others have taken matters into their own hands.

The Silent Sam legacy continues to cast a shadow on the university, with a controversial $2.5 million deal, nullified last year, that sought to give the N.C. Sons of the Confederate Veterans the statue and the money to display it.

Earlier this year, the UNC System also settled a lawsuit with DTH Media Corp., the parent company of UNC’s student newspaper The Daily Tar Heel, over alleged violations of the Open Meetings Law tied to the Silent Sam deal.

In a similar vein, the Board of Trustees only lifted a 16-year ban on renaming buildings last summer, after significant demand from members of the campus community and alumni.

In her statement Tuesday, Hannah-Jones said the work of driving change for racial justice often falls on marginalized people.

“It is not my job to heal this university, to force the reforms necessary to ensure the Board of Trustees reflects the actual population of the school and the state, or to ensure that the university leadership lives up to the promises it made to reckon with its legacy of racism and injustice,” Hannah-Jones said.

Michelle L. Thomas, president of UNC’s Black Student Movement from 1991-93, believes the structural racism at the university has intensified. People of color on campus have been dehumanized, she said. In particular, she cited the work of student activists to set up a system in 2019 to alert individuals when white supremacists are spotted on campus and recent allegations that Acting Police Chief Rahsheem Holland assaulted Black students at a June 30 trustees meeting.

“We encountered a system [in which] not only did they not celebrate Black contributions, or contributions of communities of color, they worked aggressively to stifle our voices,” Thomas said. “But what the students and the faculty and staff are dealing with today is significantly worse than it was then.”

Thomas said she loves her alma mater, but “the systems were not designed for us.”

“You would think with the public discourse that has been taking place in the past year, that our flagship public institution, the oldest public university in the nation, would be at the forefront of leading the change,” she said.

“It is exhausting for Black students, faculty and staff and their allies to have to constantly be in a state where we are pushing, pushing, pushing for the basic things that everyone else has,” she said.

Thomas has volunteered to assist Black students across the country through the college admissions process, often helping them to choose UNC. She said she will no longer do that, and that she’s since sat down with her 13-year-old son to begin thinking about other universities.

‘A pattern’

Renée Alexander Craft, an associate professor in UNC’s Department of Communication, was a student member of the Black Cultural Center advisory board at UNC during the 1990s.

Alexander Craft also participated in the June 25 BSM rally to protest the trustees’ initial refusal to give tenure to Hannah-Jones. It was important for her to attend, she said.

“As a Black alum and as a Black faculty member, I know what it is to also exist in a network of care of people reaching back, people reaching to the side, people reaching up and down from every direction, to try to keep one another safe,” she said.

Hearing from current students that part of the Black experience at UNC is marked by trauma breaks her heart, she said.

“The long work of making institutions that were not created for Black mobility and for Black excellence — to make them allow space for that — is a process that is ongoing,” she said.

Brandon Nwokeji, a rising senior in the Hussman School of Journalism and Media, said he has enjoyed his academic experiences at UNC, but is also glad to see racial injustice being brought to light. He said he questions why he hasn’t seen significant reform.

“It seems like just kind of deja vu,” Nwokeji said. “It’s this kind of a pattern of [the university] going into the media for this negative event, and this negative event, but we don’t really see any lasting changes.”

Nwokeji said the role that donors play at the school should be re-evaluated.

School namesake Walter Hussman Jr., who has pledged $25 million to the journalism school, had expressed concern about Hannah-Jones but also said her hiring would not affect his contributions.

“[Hussman], in a sense, dictates the politics of the school, the infrastructure of the school,” Nwokeji said. “And students don’t really have a voice in that.”

Nwokeji also hopes to see more student representation on the Board of Trustees. Notably, Student Body President Lamar Richards, the only student member on the board, was the trustee to call the special meeting to vote on Hannah-Jones’ tenure.

In order to have change, things need to get uncomfortable, Nwokeji said.

“And so I’m actually excited for things to get more uncomfortable,” he said. “Because we need to start holding this administration accountable for improving upon the wrongdoings of the past and not just shying away from them.”

Maydha Devarajan is an intern at The News & Observer, supported by the North Carolina Local News Lab Fund at the North Carolina Community Foundation.