Del Mar College faculty discuss impacts of racism locally and statewide

Examining racism in the Coastal Bend, Del Mar College faculty outlined housing discrimination in Corpus Christi, voting restrictions and maternal mortality in Texas and threats to the local Hillcrest neighborhood.

The forum took place in a lecture hall full of students Tuesday evening.

The Del Mar College Social Sciences Department hosted the symposium focused on race-related issues. It included presentations from seven sociology, psychology, history and political science faculty members focusing on local history and current issues.

Sociology instructor Will Rushton started off the event with a brief introduction telling students that racism is not dead in the U.S.

“It’s been argued that race doesn’t matter much anymore – that we’ve elected a Black president, so all is good,” Rushton said. “But that’s not the case.”

Over the course of the evening, the speakers cited data showing racial disparities across all aspects of society, from maternal mortality rates to disciplinary rates in schools.

Assistant professor of sociology Isabel Araiza focused in on institutional racism in Corpus Christi. Adjunct history instructor Mauro Sierra spoke about redlining in Corpus Christi.

Araiza said that the boundaries of race are not clearly defined – instead, they reflect social conditions, location and historical moments.

For example, the U.S. Census does not identify Hispanic or Latino as a racial category, and instead considers race and Hispanic origin as two separate and distinct concepts. But in the Coastal Bend, Mexican Americans have often been treated as belonging to a separate racialized category.

Araiza displayed copies of birth certificates from Corpus Christi and Robstown showing babies whose race was identified as Mexican or Latin American.

Segregation and redlining

Corpus Christi doubled in population between 1930 to 1940, and doubled again between 1940 and 1950. As developers, built neighborhoods in Corpus Christi, they included restrictive racial covenants.

In neighborhoods intended for white residents, contracts prohibited land from being sold or leased to or occupied by Black or Hispanic individuals. The only exceptions were for domestic servants.

“We couldn’t live there, we couldn’t rent there, we couldn’t own there, unless we were a domestic servant,” Araiza said. “...Subdivision, after subdivision, after subdivision, after subdivision had this in there.”

Black residents were segregated initially in the north close to Refinery Row, in the Washington-Coles neighborhood and eventually spreading into the Hillcrest area.

The Hispanic population grew in the Westside, also near industrial growth.

“There’s real consequences to being a racialized minority,” Araiza said. “Those quality resources like housing and education were not for us.”

Araiza cited a 1944 Corpus Christi housing report that stated that growing Black and Hispanic populations in white areas would devalue property.

“When redlining ended, when those restrictive covenants were no longer legal, the social landscape of our society was already built,” Araiza said.

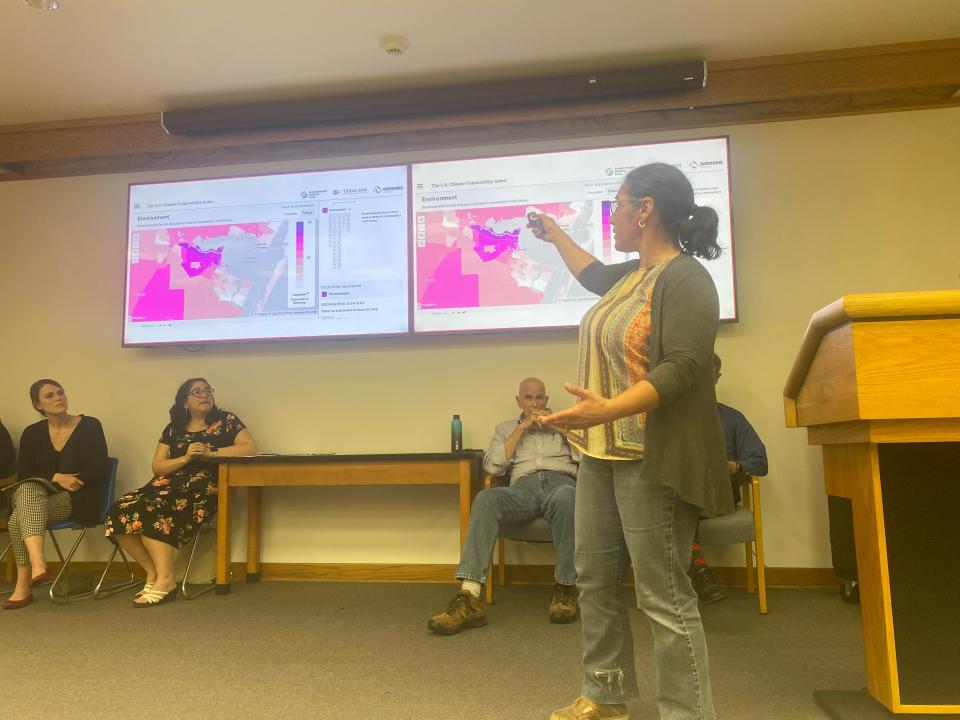

Araiza flipped through maps showing climate vulnerability, health stressors and environmental factors. In the maps, the Northside and Westside neighborhoods stood out, facing more threats than other parts of the city.

"We can dream better and we can demand better and we can deserve better and we can get better,” Araiza said.

As the city further developed, Interstate 37 was built through historically Black neighborhoods. The new Harbor Bridge will also cut through Hillcrest, and the city of Corpus Christi has plans for a desalination plant. The Caller-Times has written about how development has impacted the area and how residents have fought for their homes.

“That is going to essentially destroy a cultural area in Corpus Christi,” Sierra said.

In the late 1960s, Mexican-American families filed a lawsuit against the local school district, Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School District. In 1970, the courts found that the district had been operating separate education systems for white students and Black and Hispanic students.

Voting rights

Political science professor Adrian Clark presented on the history of voting rights in the U.S., describing a series of “peaks” and “troughs.” From the founding until the Civil War was a trough, Clark said. There was a brief peak in the Reconstruction era when voting rights were extended to Black men, but the Jim Crow era was another trough, when literacy tests, poll taxes and intimidation and lynching were used to keep Black citizens from exercising their right to vote.

The Civil Rights Movement represented another peak, but since 2013, when the U.S. Supreme Court struck down parts of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the county has been in a trough, Clark said.

The Voting Rights Act initially required states with a history of low voter registration to receive U.S. Justice Department approval before making any changes that could potentially impact voting rights. The Supreme Court declared the coverage formula used to determine which jurisdictions this preclearance requirement applied to was unconstitutional.

“Every state previously subject to preclearance requirements has changed its voter eligibility rules to make them more restrictive,” Clark said.

Clark pointed to Texas voter ID laws and recent restrictions to absentee and drive-through voting. Clark also pointed to evidence of gerrymandering, noting that current legislative district maps in Texas are drawn in ways that create white majorities.

Despite the non-Hispanic white and Hispanic populations of Texas being similar in size, each representing about 40% of the population with a slightly larger Hispanic population, 23 out of 38 congressional districts have a non-Hispanic white majority. The same is true for districts for the Texas Legislature.

Assistant professor of sociology Kelly Vinson focused on maternal health care in Texas.

The. U.S. has a high rate for maternal mortality, which measures how many women die giving birth, compared to other developed countries. The mortality rate in 2021 was nearly 33 deaths per 100,000 live births.

Rates are particularly high for Black women – nearly 70 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2021 – compared to for non-Hispanic white and Hispanic women – 26.6 and 28 respectively. Vinson said that rates in Texas were also higher than in most other states.

“I tell my students all the time, when you see different outcomes by race, that tells you we don’t have an inherently equal society,” Vinson said. “If we did, maternal mortality would be the same rate for every racial category.”

Here's how Driscoll Children's Hospital has provided therapy in Corpus Christi ISD

Academics and post-graduation readiness: Corpus Christi ISD reflects on 2022-23

Years after Corpus Christi ISD ends dual language program, other districts take it on

This article originally appeared on Corpus Christi Caller Times: Impacts of racism on Coastal Bend revealed at Del Mar College event