A Delaware library once displayed a killer's skull as a grisly Halloween decoration

What's scarier?

That Delaware once had a vicious kidnapper and killer on the loose in southwestern Sussex County who apparently felt no empathy for her victims including babies and children?

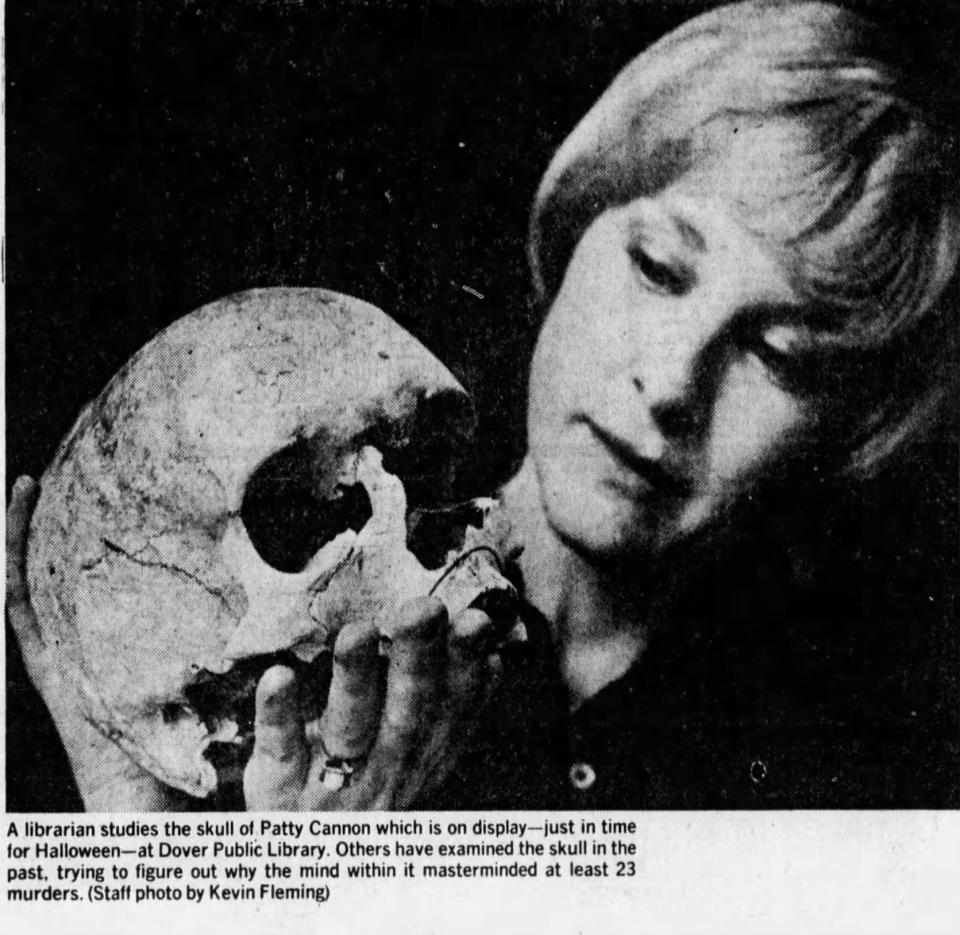

Or that Delaware authorities kept the murderer's alleged skull as a sort of grisly trophy for more than 40 years and sometimes displayed it in the Dover Public Library during the month of October as a Halloween decoration?

'The most dastardly woman'

The tale of the reputed skull of Patty Cannon has many layers to unpack.

Much of Cannon's life is shrouded in mystery, but there is little dispute that she is considered one of "the most dastardly woman in Delaware history," according to News Journal archives.

In the 19th century, Cannon, whose real name wasn't Patty but maybe Martha or Lucretia P. Hanley (newspaper accounts give both names), might have lived in Montreal, Canada. She apparently came to the Seaford area after marrying a man named Alfred or Alonzo or Jesse (again, archived stories vary) Cannon.

According to legend, he helped lead Cannon into a life of crime.

Cannon operated out of a tavern in Reliance off Delaware 20, west of Seaford, that straddled the Maryland-Delaware line. It was there that she and her son-in-law Joe Johnson, along with a gang of "thugs" and "cutthroats" they assembled, carried on "nefarious" acts of kidnapping free Black men, women and children and selling them into slavery.

Cannon, then a widow who might have killed her husband, and her son-in-law also robbed and murdered travelers who spent the night in the tavern. Cannon is said to have killed children and babies, some of whom might have been buried alive.

Various reports say that she got away with her murders and kidnappings because she was able to escape constables from one state by running into the other.

What happened to Patty Cannon?

Her luck ran out one day when she decided to take a nap in Delaware and bones were discovered on her property.

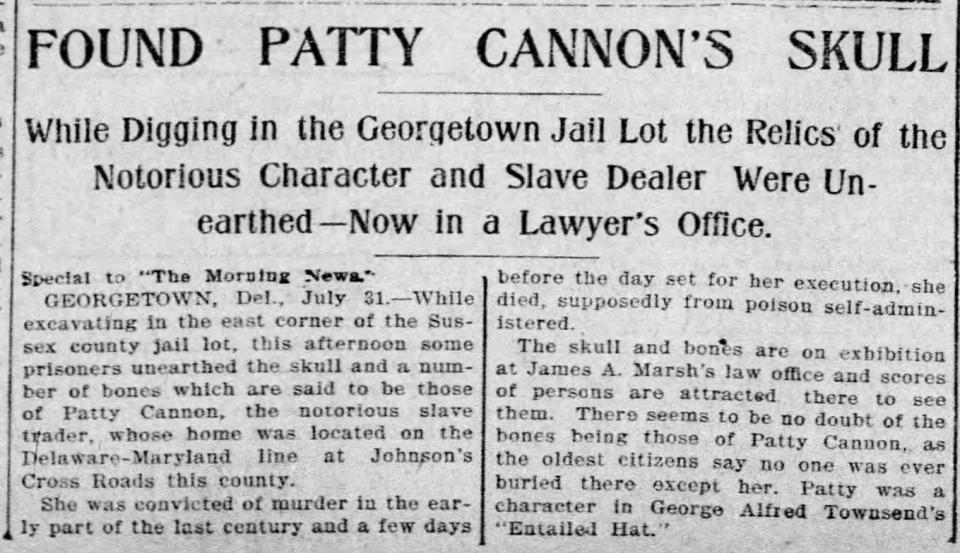

In 1829, state constables arrested her on several counts of murder and took her to a jail in Georgetown, Delaware.

While waiting to stand trial, Cannon cheated authorities, families seeking to see justice served and the hangman's gallows when she allegedly died by suicide after taking a lethal dose of poison smuggled into the jail by a friend.

No portrait of Cannon could ever be found.

Her grave was unknown although her skull and bones were reported to have been unearthed in the yard of the Sussex County jail in 1902. The skull and bones were taken to a law office. Later, the skull was given to a man who hung it on a nail from the rafters of his barn and then stored it in the attic of his home.

What does this have to do with Halloween?

Eventually, the skull was given to the Dover Public Library in 1961, where it was kept in a red velvet-lined hat box.

The skull was display occasionally for Halloween. Patrons also could see the skull any time of the year during library visits if they asked. In 2004, the library was notified it was illegal to display human remains and it was never on public view in Delaware again.

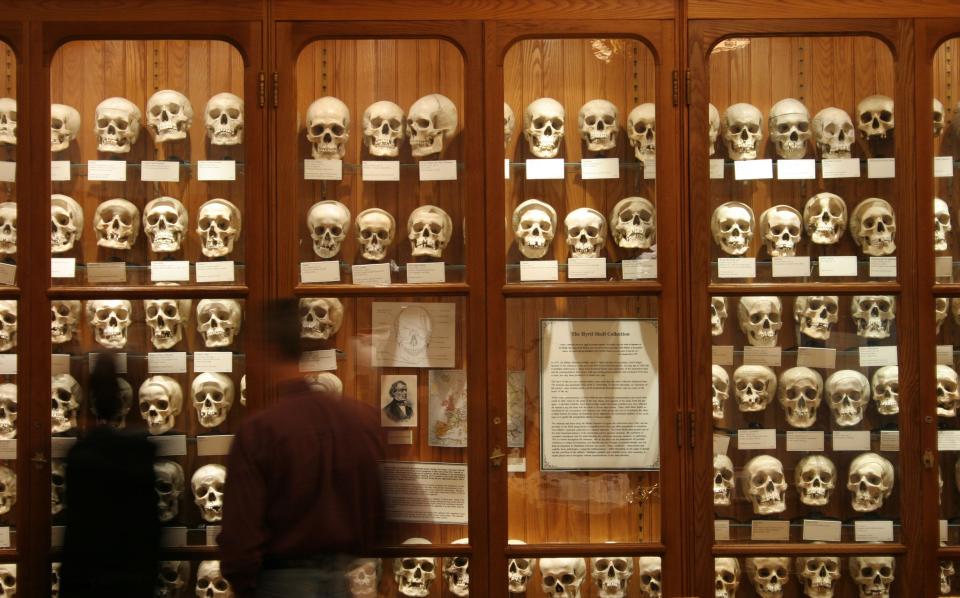

These days, places like Philadelphia's Mütter Museum, a museum of medical history in Center City, are facing ethical issues regarding human remains only display since medical consent was not given for some of the 19th and 20th-century collections in exhibits.

The Mütter temporarily removed a YouTube series for a comprehensive review by a panel of experts to ensure the content was ethical and mission-focused. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported this year that the museum had canceled its Mischief at the Mütter Halloween celebration, a popular party since 2014 because, as it was no longer pushing a "macabre, tongue-in-cheek brand."

In about 2012, the reputed Patty Cannon skull was loaned to the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History. for study when a larger library in Dover was built on Loockerman Plaza.

According to a 2013 Delaware Online/News Journal story, Smithsonian researchers said marrow analysis showed it was a female skull from someone who was about 70 years old, the same age Cannon was when she died. It could not be determined if the woman died by poison.

Where is the skull now?

The Smithsonian's Dr. Doug Owsley told Delaware Online/The News Journal on Oct. 12 that the cranium purported to be that of Patty Cannon was placed on loan to the museum by Delaware's Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs.

"They requested that we hold the cranium, feeling that the NMNH was a more appropriate repository than where it was being kept at the time," Owsley said.

He said the cranium represents an upper middle-aged woman and the original recovery context is believable although somewhat vague.

"Further research is needed to secure additional information," Owsley said. The skull was kept in a locked case in a laboratory while in the Smithsonian's possession.

It was not on display. No genetic testing has been conducted.

"We are working on several historical cases to expand the Identical by Descent research underway with Harvard University’s Ancient DNA Laboratory. This type of research could be used to establish the identity of the Delaware cranium. Due to the priority of our Chesapeake research, I decided to return the cranium after completing our baseline analysis. This would allow future testing by another qualified scientific team," he said.

The skull has been returned to Delaware's Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs, Owsley said.

"Do you remember?" is an occasional News Journal/Delaware Online feature that looks at the history behind long-gone Delaware buildings, objects, businesses, and places.

Contact Patricia Talorico at ptalorico@delawareonline.com or 302-324-2861 and follow her on X (Twitter) @pattytalorico Sign up for her Delaware Eats newsletter.

Do you remember? His eyes glowed red, he wore a skirt & seduced Lana Turner. Remembering Smyrna's 'demon'

This article originally appeared on Delaware News Journal: The skull of a Delaware killer was once a public Halloween decoration