Are Delaware schools meeting new Black history requirements? Not yet. Here's why

He tried to do it all.

By his senior year at a vocational high school, Aa’Khai Hollis would reach for leadership, including within a Black Student Union. The teen would help organize his state’s first Black Student Summit alongside Delaware’s Racial Justice Collaborative and contribute to new state legislation, all before leaving for an HBCU last fall.

There, over 80 miles from home, he’d learn another lesson.

“I was robbed of my history,” he said. Feeling sidelined in certain discussions at Bowie State University, the freshman found himself unfamiliar with subjects or figures who looked like him.

“We were talking about Black history, and some of the conversations I had to sit out on,” Aa’Khai continued. “It hurt my heart.”

Now, one law is supposed to deliver more for Delaware kids.

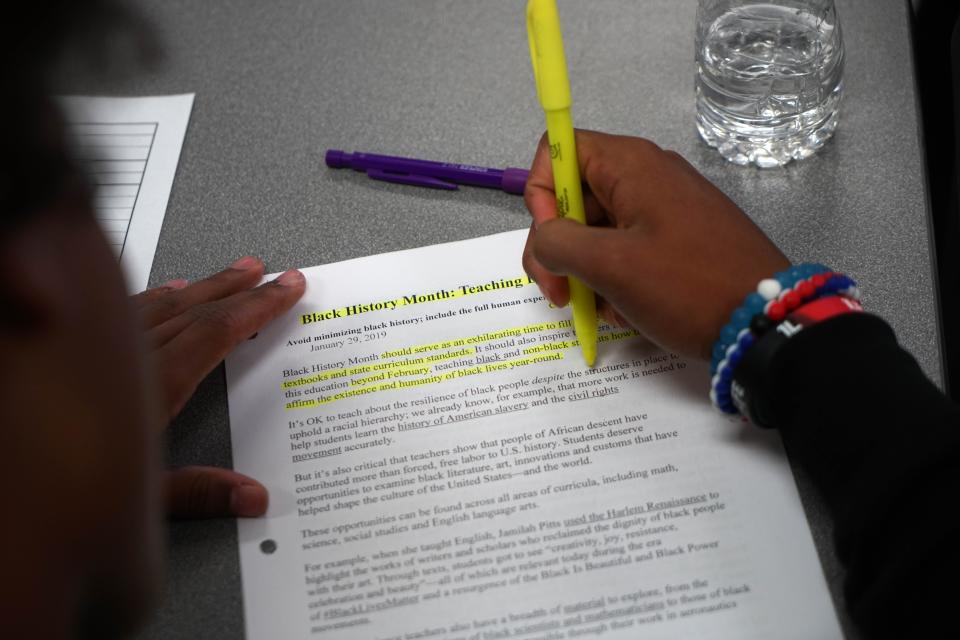

The historic legislation dubbed House Bill 198, passed in 2021, requires all Delaware public schools — both district and charter — to infuse instruction of Black History and experience into K-12 curricula.

This year marked the implementation deadline, by law. This semester offered the first full report from the Delaware Department of Education.

Over 900 pages, now online, look to capture the currents of new lessons, content and focuses flowing between Delaware's districts. But from community meetings to family inquiries, Delawareans want to better understand where schools are now — and what measures are in place to test the water’s depth.

In striking contrast to news from some conservative states, the law gave 19 school districts and 23 charter schools about a year to update all curricula with contributions of Black people to American history, life, literature, economy, politics and much more.

Each system has begun spelling out where they are now. There would be no single content package to purchase. Schools were encouraged to lean on primary, firsthand sources and seek out local history when developing curricula. Families or students who do scroll through the report might be hard-pressed in some cases to determine what’s new, what had been previously met by their district or what's yet to come.

Aa’Khai remembers standing alongside lawmakers to form and push the historic legislation, originally birthed from students, Black Caucus and sponsoring Rep. Sherry Dorsey Walker.

As this student put it, “Accountability is definitely the next piece.”

But it seems that could look different in about 42 places.

'How deep do we want to get?'

Deangello Eley wouldn’t call Aa’Khai’s story unique.

The assistant principal at Appoquinimink High School remembers feeling the same way, and he said as much when speaking to his school board about the new law.

“I remember saying that I shared that same feeling, because I don't know where I came from. I can maybe go back a couple of decades, in terms of my own history. Multiply that by millions of Black people,” he said.

“And not knowing that history, not just for Black people, for white people and other groups that don't know our history — it’s hard for people to empathize with our story.”

The new law came with requirements for curricula across K-12:

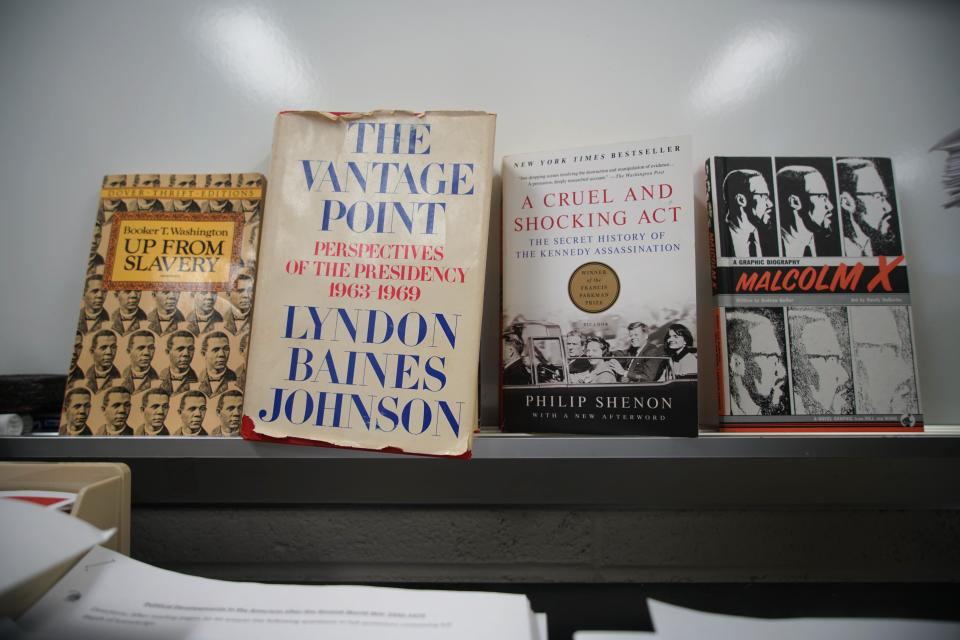

The history and culture of Black people before the African and Black Diaspora, including contributions to science, art and literature.

The significance of enslavement in the development of the American economy.

The relationship between white supremacy, racism and American slavery.

The central role racism played in the Civil War.

How the tragedy of enslavement was perpetuated through segregation and federal, state and local laws.

The contributions of Black people to American life, history, literature, economy, politics and culture.

The socioeconomic struggle Black people endured and continue to endure in working to achieve fair treatment in the United States; as well as the agency they employ in this work for equal treatment.

Black figures in national history and in Delaware history.

Background from 2021:Delaware lawmakers pass bill to mandate teaching Black history in schools

Each district and charter school had to appoint a lead, who now reports where these requirements are being hit in instruction, by grade level, to the state education department. The department then compiles an annual report as required by the law, sending it to the governor, members of the General Assembly and the Division of Research.

Though full implementation was required this year, it’s clear in the report’s language and conversations with Delaware educators that this isn’t the case.

“It looks a little bit like throwing darts,” said Michael Feldman, social studies education associate with the Delaware Department of Education. “Because it is. During this first year of implementation, districts are making sure they attended to each one of these things.”

The education department stressed its role in the legislation is supportive, not evaluative. Similar support has come from the Social Studies Coalition of Delaware, professional development for teachers and more.

“We started with social studies,” Feldman said, with the new law's requirements leaning heavily on history. Many districts began with laying out what was already being taught, he said, and where new requirements fell short.

"But we recognize that culturally responsive education, Black history, is throughout all content areas," which is why he said English Language Arts, Visual Performing Arts and even science are looking at how it fits there, too.

Some buildings like Eley's are still “on the ground floor" of this work, as he put it, still boosting buy-in across the school community. He says teacher support will be crucial, as many feel concerned they don’t yet have the tools for these conversations.

“I take it personally that this Black History education actually gets implemented — not only implemented but infused into every content area, in our districts, across the entire state,” he said, estimating this lift might take closer to five years.

“Some people may go a mile wide, and only an inch deep. How deep do we want to get? It depends on: How do we define success?”

That’s a great question.

Who defines success in implementing more Black history? It might be you

Similar concerns echoed across Zoom meeting tiles just last week.

Let The Truth Be Told, an advocacy group now focused on the complete implementation of this law, hosted over 50 people at a virtual meeting March 1. Many listeners wanted to understand where safeguards were. How can they know the content requirements are spread throughout the year? How can they know their district is following through?

“This legislation needs teeth,” one participant said before re-muting.

As it stands, the onus seems to fall on schools and their communities.

Several district leads were on the call. New Castle County Vo-Tech said it plans to turn to professional evaluations and student conversations. Brandywine chimed in saying it’s focused on bolstering student leadership opportunities to keep a feedback loop for new curriculum, while stressing Black History Month is an entirely separate celebration. Multiple districts present said it’s clear collaboration is coming from more than social studies. Delaware State University's Early College School added continuing professional development will be key, meeting a chorus of nodding agreement.

State boosting minority firms:Delaware using pilot studies to increase diversity in state-funded construction projects

It really is “a little tricky,” as Monica Gant, associate secretary of academic support with the state education department, put it.

“We have not been asked to determine what success is,” she said. “Charters and districts, they're engaging with their students to find out if it's meeting their needs, if it's what they anticipated. I think all of those pieces will certainly identify success, but there's not going to be kind of a report card.”

Her education department colleague Feldman agreed.

“When we meet with communities we reinforce that, but also say they're really the arbiters of what is successful,” he added. “So all the more reason they should go to their district’s report.”

The report has the leaders for this law's implementation spelled out for each school system. And in Red Clay, that name is Holly Golder.

The supervisor of social studies has been working toward implementation since the original bill was being drawn up. Last year saw the height of preparation, she said, particularly in meeting requirements for K-3 levels. She knows there’s more work to be done.

“The learning experiences, the lessons we’re designing, we are making sure that they're being implemented in classrooms, by putting them in pacing guides, by having constant communications with our administrators,” she said.

From piloting AP African American History, to tuning age-appropriate discussions of racist history for elementary, she knows each school in her large district reflects a different starting point.

“We are committed to continuing to grow, to make sure that students are seeing themselves and learning about others in our curriculum,” Golder said. “We're not going to have it perfect year one."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY NETWORK: Delaware schools required to teach more Black history under new law