Delaware's Inland Bays get a 'D' rating. Pollution, development, climate change to blame.

The nonprofit Delaware Center for the Inland Bays gave the Inland Bays a “D” rating – again – in the 2021 State of the Bays report released Monday.

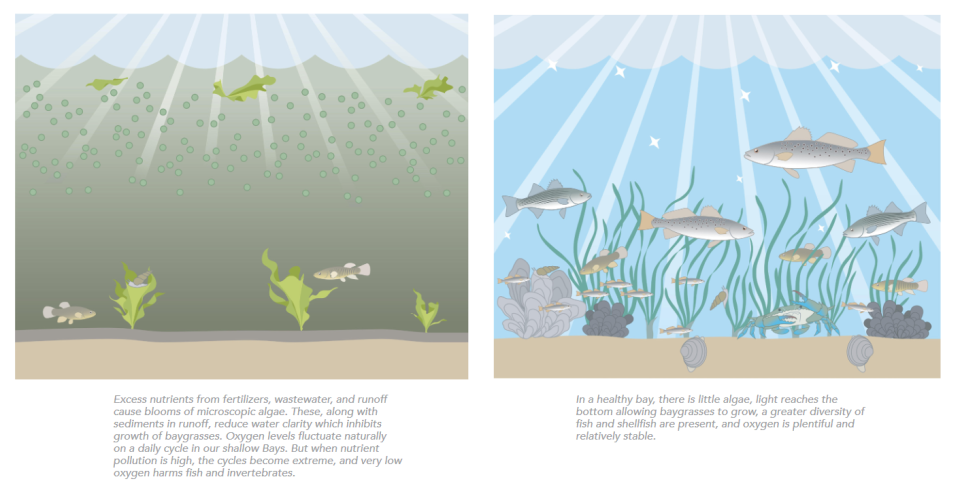

“Years of accumulated nutrient pollution and habitat loss have changed the Bays to generally murky waters that are dominated by algae, have very few bay grasses or oysters, and do not support healthy oxygen levels in many areas,” the report states.

Issued every five years, the report features data on Delaware’s three Inland Bays: Rehoboth, Indian River and Little Assawoman. The state of the bays is assessed through 39 “environmental indicators,” including watershed conditions, nutrient pollution, water quality, plants and animals, human health risks and climate change. The 2016 report also gave the bays a "D."

The bays, a popular recreational resource for locals and tourists alike, are responsible for $4.5 billion in regional economic activity, according to the center. They’re also a critical habitat for wildlife such as horseshoe crabs, oysters and diamondback terrapins.

At a press conference at Hyatt Dewey Beach on Monday morning, Center for the Inland Bays Executive Director Christophe Tulou spoke alongside report co-author and former Center Science and Restoration Coordinator Marianne Walch, Environmental Protection Agency regional administrator Adam Ortiz, and (by phone, due to traffic delays) Sen. Tom Carper.

Here are the key takeaways from the report and press conference.

The overall quality of the Inland Bays’ water is dismal

Data collected from over 30 monitoring sites in the bays found water quality in the bays is “poor to fair,” according to the report, with high nitrogen, phosphorus and algae levels and poor water clarity.

“There is still way too much nitrogen and phosphorus going into our bays,” Walch said. “That pollution comes from … wastewater, fertilizer and animal waste, as examples.”

Overall nitrogen concentrations have increased since the 2015 study, and 42% of monitoring stations had unhealthy levels of algae. Fish kill events, caused by low levels of dissolved oxygen, reached a record high in 2021, the report says. There are only a few sparse patches of baygrasses, an indicator of healthy water, in the bays.

The further inland the water, the worse the quality trends, according to the report. The upper Indian River has particularly low quality, the report says, while water in larger and more well-flushed areas of the bays tends to have better quality.

Development, lax environmental policies play a big part

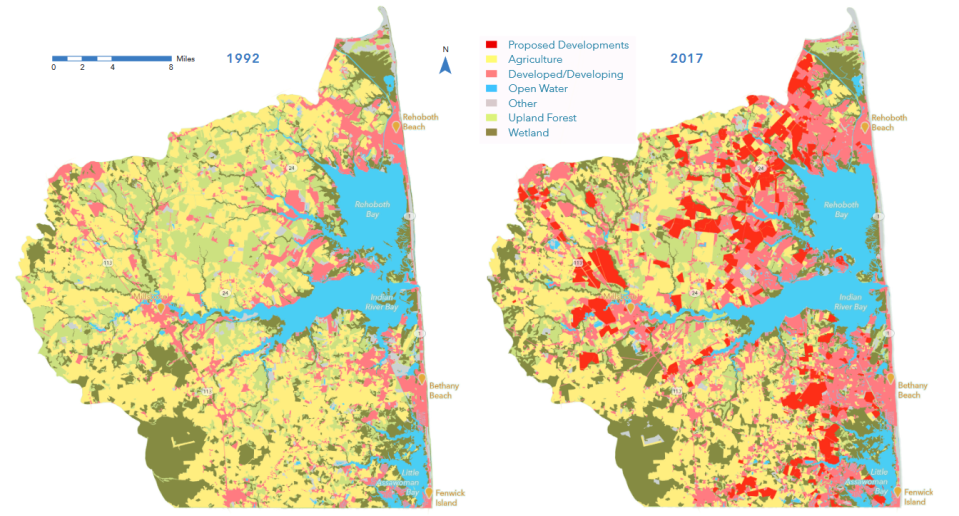

All three of Delaware’s Inland Bays are in Sussex County, where many people are moving and many houses are being built.

Between 1990 and 2020, Sussex County’s population more than doubled, according to the report. That number has only grown, with a record number of building permits issued in 2020.

“Much of the new development is near water. That’s where people want to live, but it’s also where it has the most impact on the Inland Bays," Walch said.

With development comes more impervious surfaces, such as houses and roads, the report points out. Those surfaces prevent water from soaking into the ground, and it instead flows to waterways, causing increased pollution and flooding, according to the report.

That’s not the only threat from development.

Sussex County’s buffer policies, or laws that require space between development and water or wetlands, “continue to be the least protective among those of nearby counties and states,” the report says.

Though the county increased the width of buffers required for new subdivisions last year, they aren’t required to be forested. Forested buffers offer the best protection from flooding and pollution, according to the report.

It’s not just new housing developments that need buffers. Agriculture is still the No. 1 use of land in Sussex, according to the report, and buffers are not required for croplands.

The state does require fertilizer management planning and has incentivized manure sheds to prevent runoff, but there are many more best practices to prevent water pollution that simply aren't being implemented, much less required, on Delaware farms, according to the report. There’s not much stopping fertilizer from flowing into waterways.

“Until nutrient inputs to the bays decrease, water quality will remain impaired,” Walch said. “That will threaten bay ecosystems and the natural resources that we value and that support much of our local economy.”

Climate change isn’t looming – it’s happening

“Our sea levels are rising, our marshes are disappearing, our shorelines are eroding,” Tulou said at the press conference.

Delaware has the lowest mean elevation in the country. The sea level has risen over a foot since 1900 in Lewes, the report says, and about 2 inches since 2015. It’s expected to rise 2 more feet by 2050.

It’s hotter in Delaware, and the warm season lasts longer than it did in the past. The hottest temperatures on record in Delaware, since 1880, all occurred after 2011, according to the report. The length of periods between frosts is lengthening by over a week per decade, the report says.

What it all amounts to is threats of flooding, saltier groundwater, the loss of wetlands and more pollution, according to the report. Without human intervention, the effects could be devastating.

How to fix the Inland Bays

“Put policies in place to protect the remaining buffers and natural habitats and work now to mitigate and adapt to the effects of climate change,” Walch said at the press conference.

Funding and incentives for preserving and creating wetlands, using forested buffers and cover crops and installing stormwater drain retrofits are needed, according to the report.

The Inland Bays Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan lays out the details, Walch said. It’s a matter of action from government officials, developers, farmers and landowners.

“Much of what we’ve accomplished so far is low-hanging fruit,” Walch said. “Many harder challenges remain that must be addressed with strong actions and strong commitment in order to achieve healthy bays.”

Shannon Marvel McNaught reports on Sussex County and beyond. Reach her at smcnaught@gannett.com or on Twitter @MarvelMcNaught

This article originally appeared on Delaware News Journal: How pollution, development, climate change are hurting the Inland Bays