Delaware's PIT Count: A snapshot of homelessness in the First State

In the face of bitter temperatures and sometimes perilous weather conditions, there may be no population more at-risk than individuals and families experiencing homelessness.

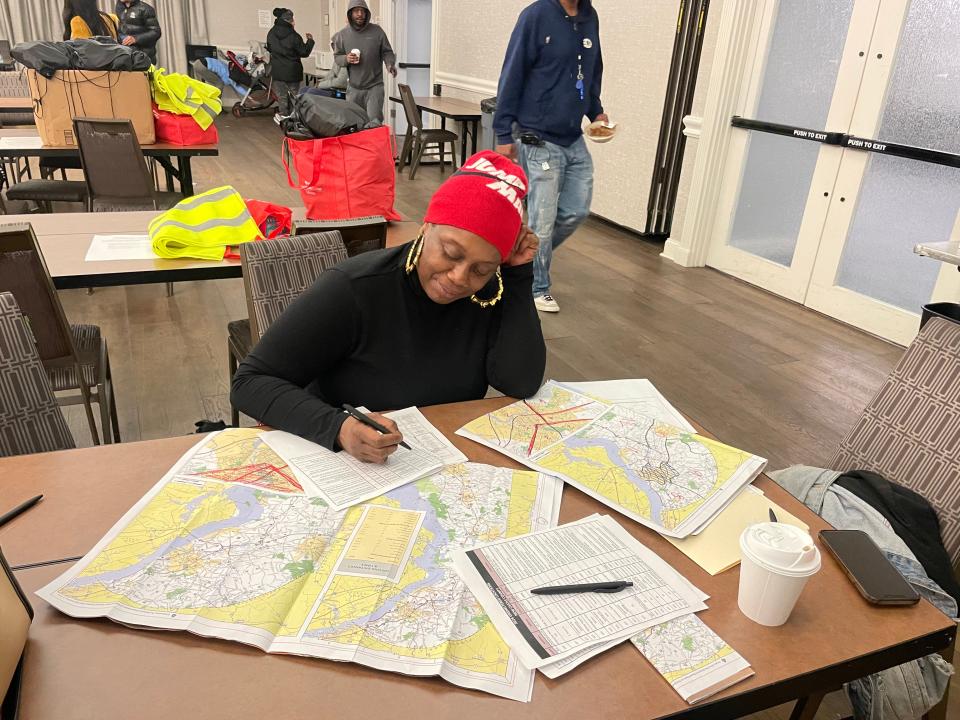

Understanding how large and widespread this community is in Delaware is crucial to securing funding and reshaping policy. Late in the night of Jan. 24 and into the early hours of the morning, community members gathered in New Castle’s Hope Center, equipped with care bags, surveys and maps to partake in Delaware’s annual Point In Time count.

As affordable housing problems continue to take center stage in legislative spaces and the pool of pandemic-era support is all but dry, the PIT count attempts to get a snapshot of Delaware’s homeless population during the most dangerous time of year.

It could be months before the final data comes back, but previous years have shown that Delaware’s lack of affordable housing and dwindling support has not only made people more vulnerable to homelessness but also has made it harder to track.

Here’s an inside look at Delaware’s 2024 PIT Count, and what it could mean for the future of housing in the state.

More: Amid the housing shortage, why is renovating homes in Wilmington so expensive?

What is the PIT Count?

The federal Department of Housing and Urban Development requires that each state conducts a “Point In Time” count every year, counting unsheltered people around the state as well as the number of people staying in known shelters designated for homeless and vulnerable populations. The data is used on a statewide and national level to inform policymaking and advocacy decisions

Typically held overnight at the end of January, volunteers venture out into known locations where people take shelter, armed with surveys and care bags full of supplies such as menstrual products, winter clothing items, Narcan, water bottles and more.

The count is intentionally held during cold winter nights to gauge how many individuals and families are unable to access emergency shelter in potentially dire situations. Public benefit payments usually are granted to individuals at the beginning of each month, so surveying the state toward the end of the month helps count people whose housing status is dependent on these benefits.

Housing Alliance Delaware, a statewide nonprofit dedicated to ending homelessness and expanding housing opportunities in the state, has been conducting the PIT counts since 2007.

Preparing for the PIT Count

Erin Gallaher, program manager for Housing Alliance Delaware, has been with the organization for six years and has planned the last four PIT counts.

The planning process begins in the summer for Gallaher. The website is built, sponsors and volunteers are lined up, a list of “known locations” is compiled and updated, and routes are mapped for teams to be dispersed.

When speaking with the volunteers, Gallaher stresses the importance of the count. Oftentimes funding for housing-related issues is reliant on the results of the PIT Count, and getting the numbers and demographics of people without a safe place to stay is crucial to accurately evaluate the problem.

More: Homelessness and addiction are intertwined. How state, local organizations plans to help

Surveys are given to volunteers who are asked to collect general information about the homeless individuals they encounter, but ultimately to respect the wishes and privacy of the people they meet. The general rule of thumb seems to be if someone doesn’t want to talk, hand them a care bag, mark a tally and keep moving.

The surveys ask questions like where the individual is sleeping that night, whether they have health insurance, direct reasons for their unhoused status and other demographic markers that contribute to the data. Using this information, volunteers can better understand what root causes exist that may contribute to someone's unsafe housing situation.

Rachel Stucker, executive director for Housing Alliance Delaware, recounted a case in Kent County just last week in which a family spent the night in a parking lot after being evicted from their home that afternoon.

“They had cars full of their belongings, and their pets with them,” Stucker said. “Delaware needs to make some real changes and real investments in affordable housing. If we don’t do something different, we are going to continue to see more of our neighbors and family members on the streets.”

“We are firm believers that housing is a human right,” Gallaher said. “The PIT Count itself assesses the problem from year to year of what’s going on in or homeless response system and what the need is.”

What does the data say for Delaware?

The last few years have told a complicated story of homelessness and accessibility to emergency assistance in Delaware.

PIT Count for 2020 was taken before the height of the pandemic and marked Delaware’s highest count since the surveys started totaling 1,165 individuals.

Due to the pandemic, between 2021 and 2022 more assistance was granted by the federal and state governments to interim housing shelters and seasonal motels. With more known places for people to stay, PIT Count numbers drastically increased in these two years.

After voucher funding expired at the end of 2022, last year told a very different story. At that time, 1,245 people were counted, a much lower number than the previous two years, but higher than any other pre-pandemic year.

More: John Carney gives final budget address as Delaware governor: Watch replay

The Delaware Journal of Public Health reported that with the drop in voucher funds, more Delawareans went unsheltered, which is notoriously more difficult to count and track for the sake of the survey.

“This drop in the PIT count will likely be framed as a reduction in the homeless population,” the journal said. “Our analysis here indicates that cuts in the availability of interim housing better explains this reduced count.”

While local progress has been made with projects like the Hope Center, the journal’s report concludes that concentrated statewide efforts will be needed to fully address the root causes of homelessness in Delaware.

Looking ahead

Data for this year likely won’t be finalized until spring, but the PIT Count data can’t be relied on to tell the full story of homelessness in Delaware, or anywhere.

Gallaher explains that because the PIT Count tracks the population surveyed in one winter night only, it could be leaving out key demographics including homeless youth, people temporarily crashing with a friend or family member, or during the summertime when people are usually less likely to take people in to protect them from the elements.

As a major election year begins, Gallaher believes the final numbers gathered in this one night will be used in legislative discussions about housing and the root causes of homelessness.

“It may not be the most reliable or valid data that we have, but it is some of the most important data that we have,” Gallaher said. “Aside from getting the numbers, it’s just a really good opportunity to engage with people across the state and make sure that in the dead of winter, we’re getting something to them.”

Molly McVety covers community and environmental issues around Delaware. Contact her at mmcvety@delawareonline.com. Follow her on Twitter @mollymcvety.

This article originally appeared on Delaware News Journal: Delaware holds annual PIT Count, connecting with homeless population