The Delusional, ‘Culty’ Giant Behind WeWork’s $47 Billion Implosion

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

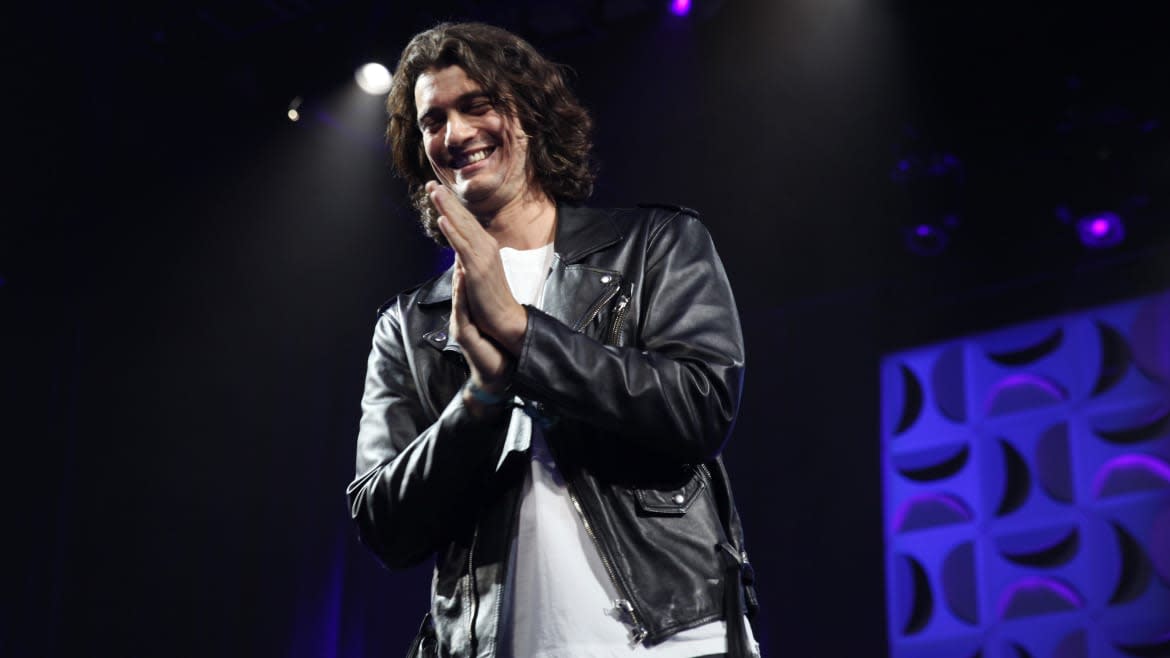

For almost a decade, Adam Neumann convinced millions of people he was a genius. Actually, that may not be hyperbolic enough. He convinced them he was a messiah, or at least one in his own mind.

He is the co-founder and former CEO of WeWork, the company that set up flexible shared workspaces for start-up companies by selling them as not only desks and square footage, but the opportunity to be part of a vibrant new community of like-minded, energetic professionals.

As The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson explains in the new documentary WeWork: Or the Making and Breaking of a $47 Billion Unicorn, “It was a period where you were rewarded if you could articulate a vision of your company that wasn’t just going to make money, it was going to change the world.”

Neumann, the 6-foot-5-inch Israeli American entrepreneur, preached in countless fawning interviews and speeches—typically served as a finely chopped buzzword salad—that WeWork wasn’t about office space. It was a revolutionary, globally connected network. Dorm buildings, dubbed WeLive, were built to house community members. There were retreats, internal Facebooks, private schools for children, and buy-in opportunities.

WeWork morphed into a “WeWorld” on its way to a staggering $47 billion valuation in January 2019—then, in one of the most astonishing flameouts in corporate history, a complete and total collapse just one month later when its S-1 filing for an IPO made headlines for its incoherence, disclosure of epic losses, and untenable business model.

The New York Times called it “an implosion unlike any other in the history of start-ups.” Making all of this—the fudged numbers, the plummeting valuation, and the thousands of lost jobs—all the more infuriating was the revelation that, after being forced to resign, Neumann received a $1.7 billion exit package for his incompetence.

If you’re familiar with tech-world fiascos like this, in which a self-proclaimed entrepreneurial guru promises his investors and customers the world, only to light their money on fire, it might sound perfectly appropriate that one of the first sounds you hear from Neumann in the documentary is a fart.

It’s a hell of a first impression. And, after getting to know him and the way he handled WeWork’s rise and fall, it’s arguably a lasting one.

“It was not my intention to make that a first impression so much as to demystify a very charismatic figure who has occupied many, many, many, millions of frames of TV and video,” says Jed Rothstein, who directed the documentary. “And to let you know that, when you meet him, we’re trying to go a little bit below the surface and get to know him on a deeper level as we go on this journey throughout the film.”

A WeWork co-working space is seen on May 18, 2020 in Tokyo, Japan.

WeWork: Or the Making and Breaking of a $47 Billion Unicorn, which premiered at SXSW and debuts on Hulu April 2, investigates how a popular idea about the future of coworking spaces was poisoned by the mismanagement and, ultimately, hubris of its media-star founder.

That unforgettable fart happens at the beginning of the film as footage plays of Neumann trying to record his introduction to the S-1 filing, uncharacteristically unable to summon his usual charisma and snake oil sales tricks.

It was the moment that Icarus flew too close to the sun. The emperor made his nude debut. The false prophet exposed himself. As Stephen Galloway, a marketing professor at NYU Stern School of Business, says in the film, “If you tell a thirtysomething male that he’s Jesus Christ, he’s inclined to believe you.”

We talked to Rothstein about Neumann’s unusual appeal, how so many people came to believe in his vision, the crucial turning point before his fall, and, in light of the pandemic, the shocking twist: WeWork—or at least its model—could feasibly rise again.

What was your impression of Alex before you started working on this? I wonder if it changed after spending so much time working on the film.

I came to the story thinking it was just this financial mystery about this company with this charismatic leader that rose up to be worth $47 billion and then collapsed in the span of a month. Which it did. And that's a fascinating spine to the story. But I began to think that Adam is a much more complicated figure. A number of things about him and how he captivated, motivated, and rallied people to his ideas were quite admirable and quite in line with great American traditions about charismatic, innovative leaders.

You can certainly tell through the film that plenty of people also saw him in that “inspiring start-up guy” tradition.

I also saw that a number of people felt betrayed by him and used by him at the end. The whole film to me, and Adam as a person, really had this kind of prismatic quality, the “me” and the “we” of Adam and the company. He did want to create a community. He did motivate people. It was real. It wasn’t like the Madoff bank funds that were never real. It was a real community. People really came together. They really felt something. But there was also the “me” side of it that was undercutting the community side of it. I think Adam always had this battle. My sense for him is that there was this internal battle between wanting good things and then just wanting to kind of have it all for yourself.

When I watched the clips of him giving speeches and making TV appearances in the film, it was really hard for me to take him seriously. He just seems so ridiculous, and the things he’s saying seem so “woo woo” to the point of parody. But at the same time we hear from all these employees and followers of his movement—smart, articulate people—that really adored him. Can you talk about how someone watching this should reconcile that?

I think Adam is a charismatic leader. Some people I dealt with called him “cult-like.” WeWork wasn’t really a cult, in the sense that no one was carving their initials in anyone’s genitals or forced to stay there against their will. But I do think he inspired people to leave behind everything else they were doing and get on board with his rocket ship. And in that sense, there’s a culty aspect to it. I think that the yoga-speak, a lot of which comes from Rebekah, his wife [and cousin to Gwyneth Paltrow], appeals to some people. It doesn’t appeal to me.

Clearly it doesn’t appeal to me either.

It’s interesting to me that it’s such a New York story, which I love about it. I’m a New Yorker. You’re a New Yorker. There’s something about the hustle that he had at the heart of it, which is really interesting and attractive. That kind of wellness talk woven into it I associate more with our dear friends in California, but actually it’s very much part of our story here too in New York. I think some people hear that and they’re turned off, and other people hear it and they’re like, “Yeah, this guy’s really speaking in a soulful way and he’s talking about integrating business and spirituality and I like that.”

You’re totally right. I know those kinds of New Yorkers.

Some of the sensation that you had, which I think many people have, is sort of in the eye of the beholder. Adam could be many things to many people. He could be a charismatic businessperson. For a lot of these more established real estate guys in New York, I think he was an entree into this much more exciting, sexy, wild world of startup culture. These guys are the most staid, old-line, oligopolistic real estate families in the book, and to be in a deal with Adam was like, “Oh yeah, we’re gonna seal the deal over some tequila. There’s going to be this huge party. It’s going to be off the hook.” You’re no longer just some guy who makes money in real estate and goes to the country club. You’re part of the future.

You mentioned the comparisons to a cult, and it’s hard not to think in those terms when you see how the WeWork “community” became an all-encompassing lifestyle. You alluded to NXIVM and Keith Raniere with your carving initials comment. Maybe because the NXIVM documentary The Vow or the Elizabeth Holmes documentary The Inventor are so recent in our minds, did you think that “cult” and “cult-like figure” might be where our brains automatically go?

I think there are cult-like aspects. I think people got wrapped up in the whole “WeWorld” in a way that is cult-like. I don’t think it’s a cult. There were some questions of including the term “cult” in the title, which I resisted because it’s just not really a cult. I think the gray area of it—that it’s kind of culty—makes it more interesting rather than less.

So it’s cult-like, but not a cult.

But I think the experience of some people coming out of it is probably very analogous to the way that some people experience leaving and being deprogrammed from a cult. So that’s maybe an analog to it. What makes Adam and we the WeWork story so interesting is that he was close. He was close to doing something really great. Keith Raniere was not close to doing something great. He was a predator, right? Elizabeth Holmes was a fraud. Adam was close to building this really amazing thing. It had these kind of culty aspects, but it was also a great way to bring people together and change the culture of work. There really is more of this Icarus fable sense to Adam, that he flew too high and so many people kept telling him he was the bee’s knees.

Because the rise seemed so fast and outrageous and the $47 billion valuation just seemed so astronomical, I sensed a feeling of schadenfreude when everything came crashing down. Even if just among the cynics, many relished in the failure and arrogance of it all. What do you make of that?

All these journalists—the financial press and the broader press—were happy to write, “WeWork is the most valuable, best startup in the world,” “they’re amazing,” “he’s amazing,” “he is the most charismatic, innovative visionary leader ever.” The press was very happy to build that up. Investors were happy to build it up. The $47 billion valuation came from investments by the most savvy investors on the planet—the biggest and most savvy and knowledgeable investors on the planet. It did not come from some scam where he called up a bunch of random old ladies and stole their life savings.

That’s true. As much as the meteoric rise mystified everyone, it was rooted in what seemed like tangible, smart investing. So it was believable.

These were smart investors. He charmed everyone. WeWork was so extravagant. I mean these parties that you see in the film, they were multi-day, corporate Woodstock, bacchanalian things. Adam’s tales of private jets and homes all over the place. At one point he bought Bill Graham’s home in Marin, which is in the shape of a guitar. He would fly people on seaplanes and helicopters out to the Hamptons to have note sessions on documents because he didn’t want to bother just getting on email. He would do these extravagant types of things. I think when that person is so high and flying so fast and so far and they start to fall, there’s something about that, yeah, there’s a schadenfreude. There’s a feeling that it seemed like it was too good to be true and we caught you and you’re gonna fall.

I just remember the tone of coverage shifting so quickly.

When he published that S-1 filing, which I think was sort of the height of his hubris, in a way, it was the culmination of this culture at WeWork where no one would tell him boo about anything. No one would say Adam, why did you do that? It’s either that it wasn’t said or wasn’t said enough or he just didn’t care. When the disclosures in the S-1 were submitted to the wider community of people who didn’t work for him, in the cold light of day that stuff looked ridiculous. The emperor really wasn’t wearing any clothes. I think that the financial press especially, they’re happy to pile on in any direction.

The headlines were immediately negative. As negative as they used to be positive.

I don’t want to knock Jim Cramer. But, you know, these guys put up their fingers and they try to be two seconds in front of you recognizing which way the wind is blowing. And then they all pile on and they pretend they’re geniuses. If it’s going up, everyone should get it. When it’s going down, it's the worst thing ever. So all of a sudden Adam was the biggest fraud that ever existed in the world. Was he really? No. But the company fell fast enough to make that the story. That’s the way that most people will be introduced to this. It went up to $47 billion and collapsed quickly. Which is true. We try to get behind the story: why that happened and what it means.

Many of the interviews you did with experts and past employees were shot during the pandemic. It was surprising to hear from these people, many of whom were screwed over by Adam and the company, all saying the loneliness and isolation they felt this last year is still making them crave the community and the greater mission WeWork was all about. It’s a really emotional coda to all of this, and it’s one that suggests that WeWork could tangibly make a comeback, thanks to the pandemic.

The person who I think most eloquently states that in the film is Megan [a former employee who worked closely with Adam]. On the one hand, she was clearly scarred and hurt. She went through a difficult experience at the hands of this company, psychologically. At the same time, there were values and there were elements of her experience there that were really nourishing and wonderful. She was able to make this community with other people and learn different things about herself and how she could be part of something greater than herself. She, and many people, want to hold onto that.

She’s certainly not alone. For all the talk of the incredible amounts of money, there was also an incredible number of people who just believed in this idea.

The story of WeWork is not as simple as, “I came to it thinking it was this big financial scam and we’re going to uncover how that happened and look at all the terrible people that did it.” What I learned is that there certainly was a lot of money made and a lot of money lost. But it was not one of these simple stories, because there are good and bad elements to all of it. Megan had both this difficult experience and the experience that she wants us all to find a way to hold on to. WeWork encompasses both of those things in its story.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.