Democratic Push To Diversify Primaries Runs Into Very White Sticking Point: New Hampshire

As Democrats work to reorder their presidential primaries before the 2024 election, the committee charged with selecting a new slate of states is running into a very stubborn and very white sticking point: What to do about New Hampshire, a state whose first-in-the-nation status and history of razor-thin elections has long meant it has punched above its political weight class.

The Democratic National Committee’s Rules and Bylaws Committee is set to have a virtual meeting Friday to discuss the party’s ongoing efforts to change the states that will get to hold the first presidential primaries in 2024 and beyond, giving them an outsized say in the American political process.

Almost no one involved in the process expects Iowa to retain its status as the first state to vote, through its caucus system, and there is some risk the state could lose its early voting status entirely. But New Hampshire is a trickier proposition, and finding the right answer will involve balancing competing party goals and could have a significant political effect. Nevada, one of the nation’s most diverse states, is openly gunning for New Hampshire’s spot.

The Democratic Party, which counts Black, Latino and Asian voters as key chunks of its political base, has made the diversity of a state’s electorate a key part of the criteria to determine which states will get to cast their presidential primary ballots first. By that measure, New Hampshire fares even worse than Iowa. The state is 87.2% non-Hispanic white, compared to 84.1% in Iowa, according to the 2020 census, making it the fourth-whitest state in the nation, behind Maine, Vermont and West Virginia.

At the same time, the state has done little to deserve a demotion. Iowa’s 2020 caucuses turned into a disaster, and the state’s system, which forces residents to spend hours on a weeknight casting their votes, has always been undemocratic. New Hampshire, with its open primary and same-day voter registration, has always operated smoothly, and its retail political tradition has long created an open playing field that might not be possible in a bigger state.

And its first-in-the-nation status, which the Granite State political class fiercely protects, is written into state law, with the secretary of state having no choice but to set the primary date before any other. Since Nevada Gov. Steve Sisolak (D) signed a law switching Nevada from a caucus to a primary, the stage is set for a showdown if Democrats try to move the Silver State into the first slot.

“There literally is no wiggle room,” longtime New Hampshire Democratic Party chair Ray Buckley said in an interview. “No matter who is the secretary of state, they’re going to uphold the law.”

But members of the Rules and Bylaws Committee are openly bucking against such laws and want the party to be able to consider any option.

“We need to do what’s right for us,” Mo Elleithee, a Democratic operative who serves on the committee, said during a meeting earlier this month. “I don’t like that the committee is held hostage by them, and I want this committee to make a decision based on merit.”

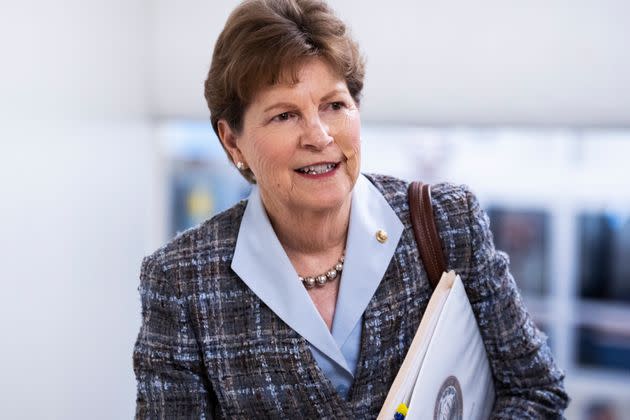

New Hampshire Democrats, led by Sen. Jeanne Shaheen, have argued that downgrading the Granite State’s primary status would hurt them politically. Democrats are defending Sen. Maggie Hassan’s seat and two congressional incumbents in November.

“We’re seeing a growing narrative that blames Democrats for jeopardizing New Hampshire’s first-in-the-nation status,” Shaheen told members of the Rules and Bylaws Committee at a June meeting, not long after the New Hampshire Democratic Party handed out swag bags to committee members. “With such a tight Senate race and newly redrawn congressional maps, I fear stripping New Hampshire of its long-held position could be consequential.”

A survey conducted by Data for Progress, a progressive polling organization, challenges Shaheen’s assertion. The poll of 903 likely voters in the state, conducted in late June and early July, found nearly two-thirds of the electorate either wouldn’t blame anyone or wouldn’t know who to blame if the state lost its status. An additional 21% would blame the Democratic and Republican National Committees.

Sen. Jeanne Shaheen (D-N.H.) has been a key defender of New Hampshire’s first-in-the-nation presidential primary status, arguing a downgrade would hurt New Hampshire Democrats politically ahead of the 2022 midterm elections. (Photo: Tom Williams via Getty Images)

The poll found just 3% of voters would blame Hassan, with most of the blame coming from Republicans. The survey also found Hassan narrowly leading all three of her potential GOP challengers in November. She earns a consistent 49% of the vote, with the Republicans garnering either 45% or 46% support.

“While New Hampshire’s status as the first primary in the nation has recently become in jeopardy, likely voters do not associate the issue with elected officials,” Data for Progress’ Kirby Phares and Brendan Hartnett write. “These results show that Senator Hassan is well positioned against potential Republican candidates, and the Senator’s re-election campaign is unlikely to be impacted if New Hampshire were no longer the first presidential primary.”

To Buckley, the poll actually drives home the risk. He notes Hassan first won reelection by just over 1,000 votes in 2016, and her election in a GOP-friendly political environment could be even closer, making any alienated voter a problem. He also pointed out Republicans have already claimed Democrats are threatening the first-in-the-nation primary because of “an obsession with identity politics.”

“They’re itching to attack us over this,” Buckley said of Republicans.

Buckley also defended the state from claims it is unrepresentative, arguing it has become more diverse and noting the Democratic electorate and officeholders are far more diverse than the state as a whole. He said only two of the 11 party officers are straight white men and pointed to recently elected Black and Latino sheriffs in the state.

“If you take out the Republicans and look at who participates in the Democratic primary, you’ll see much more diversity,” Buckley said. (Exit polls from the 2020 contest found the presidential primary electorate was 89% white.)

Nevada, which is working aggressively to claim the first spot, has a more straightforward claim to diversity: It is roughly 46% white, 30% Latino, 10% Black and 9% Asian, according to the 2020 census. It also has extremely voter-friendly laws, another factor in the DNC’s decision-making. Though Democrats have repeatedly won the state in recent years, it is not solidly blue, and a trend toward the GOP among Latino voters is threatening Democratic strength there.

“The state that goes first matters,” said Rebecca Lambe, the longtime top political lieutenant for the late Sen. Harry Reid (D-Nev.), during Nevada’s presentation to the committee last month. “We all know it does. It fundamentally shapes the start of the primary and how candidates spend their time and resources in the off-year. It creates momentum, and it sets the tone for the contests that follow up. It elevates some candidates and not others. And that’s why we believe it’s so important for the first date to look like America.”

In 2020, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and now-Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg thrived among the mostly white electorates in Iowa and New Hampshire, while Nevada provided the start of now-President Joe Biden’s comeback, and a massive primary victory in South Carolina finished it.

In part because of Biden’s fondness for the state, South Carolina’s position as the third state to vote is assured. There is a possibility Georgia could join it as a second early-voting Southern state, giving Black voters even more of a voice.

Committee members are also looking at adding either Michigan or Minnesota, either to join Iowa as a Midwest representative or to replace it entirely. Michigan’s size could hold it back, however. The state awarded 147 delegates to the Democratic National Convention in 2020 ― more than Iowa, New Hampshire and South Carolina combined. Some committee members fear that placing a state with such a large delegate haul at the front of the calendar would cause candidates to ignore other early-voting states.

The Rules and Bylaws Committee also has other issues to decide, including whether multiple states could possibly vote on the same day in the early voting window and potentially how to punish any states that try to cut in the voting line.

The committee will vote on a final recommendation during a meeting on Aug. 5 and 6. The full Democratic National Committee will then vote on the recommendation at a meeting in September.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost and has been updated.