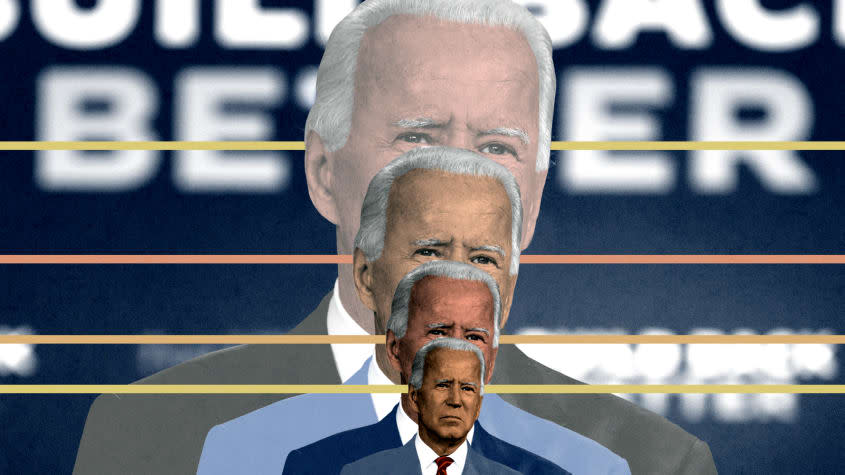

The Democrats' incredible shrinking reconciliation package, explained

Soon after taking office, President Biden unveiled an ambitious $4 trillion package to clean up America's energy policy; boost families with new health care, child care, and education benefits; slash global tax avoidance by wealthy individuals and corporations; and rebuild America's infrastructure. Over the next year and a half, Democrats — well, chiefly one Democrat, Sen. Joe Manchin (W.Va.) — has whacked those ambitions down by about $3.7 trillion.

"This week, after more than 15 months of breathtaking political pivots, Manchin has reduced Biden's big ideas for a sweeping investment to just two," The Associated Press reports: "Reducing the costs of prescription drugs and shoring up the subsidies some families receive to buy health insurance."

With Democrats holding the slimmest of majorities in the 50-50 Senate, Biden and the rest of his party's congressional delegation appear to have decided that Manchin's slice of the once-robust "Build Back Better" loaf is better than no bread at all. What are Democrats still hoping to enact through the filibuster-proof reconciliation process and, what obstacles remain? Here's everything you need to know:

What's left in the Democrats' reconciliation package?

Democrats are moving forward with two programs, one focusing on prescription drug costs, especially for seniors participating in Medicare, and the other extending federal premium subsidies for people and families who buy health insurance through the Affordable Care Act marketplace.

"Both are big Democratic priorities and would be consequential for Americans struggling to pay always high health care bills," AP reports. "Compared to what could have been, they amount to about $300 billion."

The ACA subsidies, which lower insurance costs for nearly every American buying insurance through the program instead of through their employer, will expire in December if Democrats don't extend them.

How would the bill lower drug costs?

The legislation under consideration would allow the federal government to use its purchasing heft to negotiate lower prices for a group of expensive medications bought by Medicare, require drugmakers to rebate the government if they raise prices faster than inflation, cap the out-of-pocket drug costs for Medicare users at $2,000 a year, and ensure they get free vaccines.

Medicare users currently can face annual medication expenditures of more than $10,000, so the $2,000 cap would be "a significant benefit to patients who take expensive medications for serious diseases like cancer and multiple sclerosis," Margot Sanger-Katz explains at The New York Times. "The prescription drug provisions are unusual in that they offer Americans tangible benefits — lower drug prices, more financial protections — while actually saving the federal government money."

In fact, Sanger-Katz writes, even if the prescription drug "sidecar" of the "Build Back Better Act is now the only vehicle left on the road, it would still have a substantial impact on the lives of many Americans. And unlike other provisions that faced a mixed political reception, the central health care proposal that remains is enormously popular with the public — including Republicans."

"We're on the cusp of a very big win here," White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre agreed.

So why are Democrats so glum?

A lot of their legislative hopes, once thought to be within reach, were dashed by Manchin and, in some cases, Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D-Ariz.). And it took 15 months of incremental disappointments to realize Manchin was going to say no to most of the original bill.

"Joe should have made his position clear a hell of a long time ago," Senate Majority Whip Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) said Monday. "We've wasted a lot of time on negotiation." If negotiators continued, "it's sort of like: what would be your evidence that would lead to something positive?" added Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va.). "We should have voted on some of this months ago."

Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) pointed to the thwarted climate provisions. "I am deeply frustrated, period, that what is perhaps one of the most existential threats to humanity that could cause trillions of dollars of damage to our country, threaten the life of the most vulnerable first — that we're not doing anything about that right now," he told Politico.

What's Joe Manchin's deal?

Manchin is "one of his party's most conservative members" and "a fossil fuel champion," AP notes, especially when it comes to coal, a dirty but economically important source of energy for both the senator and his home state. That puts him out of step with much of the rest of congressional Democrats, though he insisted Monday he hasn't "walked away from anything."

Manchin's stated reason for balking at the climate and tax provisions of the reconciliation bill was high inflation. "Inflation is my greatest concern because of how it has affected my state and all over this country, and that's all I have to say," he told reporters. "I don't know what tomorrow brings."

Manchin teased that he may be willing to bring back those elements in separate legislation in September if inflation recedes, but "approving a measure in the heat of election campaigns would be extremely difficult," AP notes, and Democrats may well lose control of one or both houses of Congress in November. After "exhausting themselves" over months of fruitless "negotiations with their elusive centrist," Politico reports, "Democratic senators are done trying to chase Manchin."

What could still thwart the remaining provisions?

Even if Manchin sticks with the deal, it will take all 50 Senate Democrats and aligned independents to pass the reconciliation package, meaning there are 50 individuals who can single-handedly sink or further shrink the legislation before it makes it to the House. And before it even gets to the starting gate, the bill has to pass through the Senate parliamentarian.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) has already submitted the legislation for review, kicking off "the so-called 'Byrd Bath' where the parliamentarian reviews the proposed text to make sure it abides by the Senate's reconciliation rules," Politico explains. The "bath," named after Manchin's mentor, the late Sen. Robert Byrd (D-W.Va.), "is supposed to purge extraneous provisions that don't align with the reconciliation instructions."

Ironically, "this week's wonky faceoff before the Senate parliamentarian is likely to be substantially quicker and less painful for the majority party now that Manchin has sworn off tax hikes," Politico reports, but Republicans are preparing to urge the parliamentarian to throw out as much of the bill as they can, to show that "Joe Manchin isn't the only one with the power to cut down Democrats' pre-election Hail Mary."

"We're going to fight as hard as we possibly can, and we're going to challenge as much as we believe is properly challengeable," said Sen. Mike Crapo (R-Idaho). Kaine shrugged off the threat, saying Democrats have spent months scrubbing the legislation to make sure it will comply with reconciliation rules. "We have had this idea on the table for more than a year," he said. "The parliamentarian has been in the discussion for a very long time."

If Republicans can't destroy the bill with the parliamentarian, they will try to spoil it politically. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) described the drug price provision as "socialist price controls between American innovators and new cures for debilitating diseases," adopting drug industry arguments that lowering drug prices will stifle drug development.

Durbin seems happy to have that argument. "This prescription drug issue is an inflation issue," he told reporters. "It's a public health issue. It's a cost to the government issue. And it's something the American people get."

What are the costs of leaving all the rest on the cutting room floor?

For Democrats, the failure to enact huge parts of their agenda could have a political cost, demoralizing Democratic voters ahead of the midterms. And ditching the tax and climate policies will also ripple around the globe.

The climate policies Manchin dropped from the bill — tax credits for renewable energy and electric vehicles, among other energy-related provisions — would have moved the U.S. very close to reaching Biden's pledge to cut carbon emissions by 50 to 52 percent over 2005 levels by 2031. Biden said he's worried about inflation, which is "a serious concern," Chris Mooney and Harry Stevens write at The Washington Post. "But there is always a reason to delay action, and time is not forgiving when it comes to the warming climate."

"The current official U.S. targets are ambitious," John Sterman, an energy policy expert at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, tells the Post. "They are also necessary to create a prosperous, healthy climate. And the policies that the administration had proposed — transportation, buildings, et cetera — had the potential to get us there." But now, "with Sen. Manchin's position," he added, "we're not going to be able to do that."

And Manchin's scuttling of the tax provision he spent months negotiating throws a wrench in the Biden administration's high-stakes push to "raise tax rates on many multinational corporations in hopes of leading the world in an effort to stop companies from shifting jobs and income to minimize their tax bills," The New York Times reports.

"I said we're not going to go down that path overseas right now because the rest of the countries won't follow, and we'll put all of our international companies in jeopardy, which harms the American economy," Manchin told a West Virginia radio station on Friday. "So we took that off the table."

If the U.S. can't enact the 15 percent minimum corporate tax Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has been convincing other countries to adopt, it "creates a mess both for the Biden administration and for multinational corporations," the Times reports. "Many other countries are likely to press ahead to ratify the deal, but some may now be emboldened to hold out, fracturing the coalition and potentially opening the door for some countries to continue marketing themselves as corporate tax havens."

You may also like

Rand Paul, Mitch McConnell blame each other for Biden dropping nomination of anti-abortion judge

At least 1,100 people have died in Spain and Portugal from heat-related causes