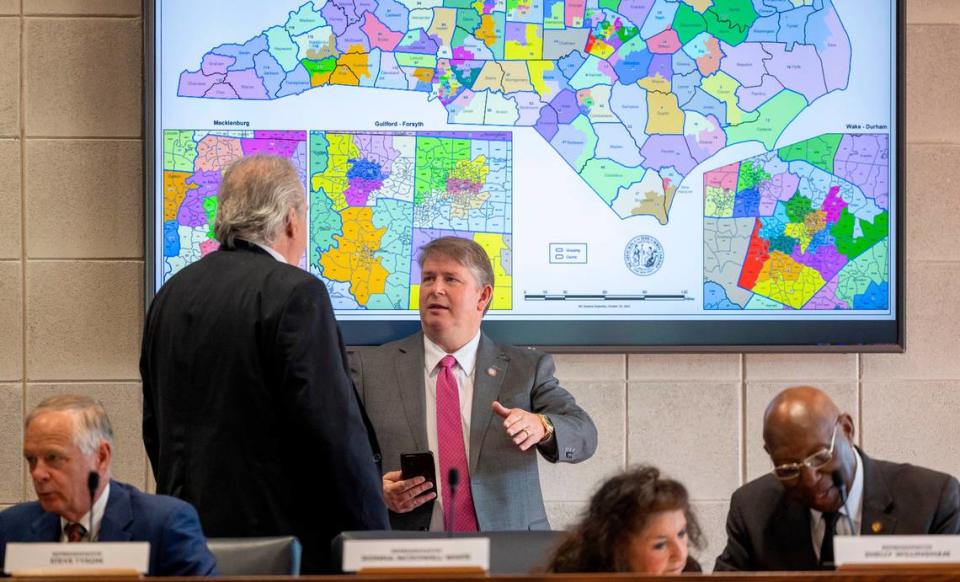

Democrats must prove racial gerrymandering to fight new GOP maps. How do they do it?

Once new electoral maps get approved in North Carolina, critics always look to the same place to force changes: the courts.

Things are different now, though, with the state Supreme Court’s new Republican majority ruling in April that it had no jurisdiction over claims of partisan gerrymandering.

Seemingly armed with impunity to draw districts that favor their party, there may only be one valid legal challenge opponents can bring against Republican leaders: racial gerrymandering.

Top Republicans, likely expecting litigation, have exhaustively repeated that the maps they approved Wednesday for the 2024 elections for Congress and the legislature were drawn without using racial data. But Democratic lawmakers, legal experts and activists are already alleging that the new maps violate federal law by diluting the votes of Black residents in key areas across the state.

“This is minority rule fighting to preserve a political gerrymander on the back of Black communities, poor communities and rural communities,” Kyle Brazile, with the NC Counts Coalition, said at a press conference before the final map votes. “The legislature has designed district maps that, despite the growth of so many of these communities, are meticulously drawn to weaken the influence and political power of the growing communities of color across North Carolina.”

These accusations could form the foundation for the next round of gerrymandering trials in a state that has fought the same battles — and often lost them — for decades.

What would a legal challenge look like?

Just a few months ago, following a series of major rulings advancing conservative interests, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down an Alabama redistricting plan for violating the federal Voting Rights Act. The court found that the Republican-drawn map diluted the voting power of Black voters, who make up 27% of the state.

The ruling offered some hope for North Carolina voting rights activists, who had worried that the court’s conservative majority would be unlikely to side with them on gerrymandering challenges.

It is, in fact, the second time in recent history that the court has upheld some level of commitment to oppose gerrymandering. In a case out of North Carolina, the court in June rejected a controversial elections theory, put forth by top Republicans, that would have given state legislatures full authority to create redistricting plans without the opportunity for judicial review.

Still, Irving Joyner, a law professor at N.C. Central University who has litigated North Carolina gerrymandering cases in the past, said any legal challenge to the maps could be an uphill challenge, considering the partisan composition of the courts.

“Those rulings give me more hope than I had before,” Joyner told The News & Observer. “But that is not strong hope.”

A successful legal challenge to new maps would likely need to focus on the Voting Rights Act, which bans voting practices that are racially discriminatory, or the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S Constitution.

Republicans have stressed that they did not use racial data to create the maps, implying that no racial animus prohibited under the VRA guided mapmaking. However, critics charge that lawmakers actually should be using racial data to ensure that the votes of racial minorities aren’t illegally diluted.

Democrats pointed to Chief Justice John Roberts’ opinion in the Alabama redistricting case, in which he notes that section 2 of the VRA “demands consideration of race.”

A major U.S. Supreme Court case out of North Carolina, Thornburg v. Gingles, sets up a test for proving vote dilution under the VRA. Plaintiffs must show a racial group “sufficiently large and geographically compact to constitute a majority in a single-member district.” They must also prove that that racial group is “politically cohesive,” meaning its members tend to vote the same way, and that the racial majority is likely to vote as a bloc against candidates chosen by the minority.

Although lawmakers did release racial statistics for the new districts after maps were released, proving Gingles conditions generally involves conducting a racially polarized voting study, which Republican lawmakers said they did not do prior to drawing maps.

“My understanding is that there’s not been presented any evidence that would justify the performance of such a thing,” Senate leader Phil Berger told reporters on Tuesday.

Further insight into Republicans’ motivations when drawing maps will be difficult to gain, considering a provision slipped into this year’s state budget that removes redistricting drafts and communications from the public record.

What districts could be challenged?

Several key districts in both the congressional and legislative maps have ignited concerns among voting rights advocates, who allege that Republican leaders are weakening the voting power of Black residents.

Of particular concern is the 1st Congressional District, which currently includes much of Eastern North Carolina. Represented by Democratic Rep. Don Davis, of Greene County, the district, as it was drawn in 2022, includes a large population of Black residents, making up about 41% of the area.

Under the new maps, NC-1, which was already somewhat competitive, becomes considerably more so. Pitt County, including Greenville, and Franklin County are removed from the district while Currituck, Camden, Wayne, Lenoir and part of Granville counties are added.

“African-American communities that could be joined together to make an electable district have not been included and instead, more white areas and counties have been commingled with those traditional African-American communities to take away voting strength that African-Americans would otherwise have,” Joyner said.

The current map for NC-1 leans Democrat by about 4 percentage points, per data analyzed using the website Dave’s Redistricting. The new map would only lean Democrat by about 1.5 points.

Former U.S. Rep. G.K. Butterfield, a Democrat who represented NC-1 before Davis, said the new maps will disadvantage an area that already struggles with poverty.

“It is a political and a racial gerrymander,” he told the N&O. “And it does not represent the demographics of North Carolina and I think it should be challenged.”

Outside of the congressional map, several legislative districts have been called into question.

The Southern Coalition for Social Justice sent a letter to Republican leaders on Oct. 22 saying that Senate Districts 1 and 2, which take up much of Eastern North Carolina, violate the Voting Rights Act. In the new map, District 2 snakes all the way from Warren County, on the northern border with Virginia, to Carteret County on the southern coast.

The Southern Coalition wrote that both districts “prevent Black voters from electing a candidate of their choice, despite both having sizable Black populations.”

The coalition commissioned a racially polarized voting study on SD-1 and SD-2 to attempt to prove a VRA violation. The study, conducted by a political science professor at the University of Delaware, reports that each of the three Gingles conditions is met in these areas, potentially opening them up to VRA challenges.

Sen. Ralph Hise, chair of the Senate Redistricting Committee, said the coalition was the only organization to attempt to provide evidence of a VRA violation.

“The chairs made the determination that nothing in the data we saw required the additional drawing of those maps specifically on the basis of race,” he said on Tuesday.

In the letter, the coalition, which has brought past legal challenges against North Carolina maps, said it had little time to review the maps before commenting.

“The fact that we write today concerning two specific Senate districts cannot and should not be read as an indication that there are no VRA concerns elsewhere in the maps under consideration,” the letter said. “Instead, the fact that a clear, impending violation could be identified even on this truncated timeline should be understood as a warning sign.”

Senate Democratic leader Dan Blue called out new districts in the southern tip of the state, where parts of Wilmington are separated from the rest of New Hanover County and placed in a more Republican-leaning district with Brunswick and Columbus counties.

“You went out specifically and targeted Black precincts, all six of them, the six heaviest Black populated precincts in New Hanover County, separated them from the rest of New Hanover County — where they’ve been having an impact as a county and on the elections in that county — and you take them over to a county where they’re an insignificant proportion of the voting population,” he said during a Monday redistricting committee meeting.

Hise denied using race as a factor.

“I think it’s obvious that the minority leader wants a map that he feels will elect more candidates of his party than what he feels this map will, but I feel like we we’ve laid out our criteria and we’ve met them and we think this map best represents North Carolina,” he said.

Now that the maps have passed, lawsuits will almost certainly follow in short order.

“We are exploring racial gerrymandering claims right now,” U.S. Rep. Deborah Ross said at a Thursday press conference organized by state Democrats. “...We’re lawyering up.”

Republican leaders say they aren’t worried.

“We wouldn’t pass these maps if we didn’t think they wouldn’t stand up in court,” Berger told reporters on Tuesday. “... It wouldn’t surprise me if along the way, before we get a final decision from courts, that you might find a court that has some problem with some part of the maps — but it’s our belief that when all is said and done, these maps will stand.”

Washington correspondent Danielle Battaglia contributed to this report.