'I was in denial': Cedar Park doctor shares the lessons he learned after his heart stopped

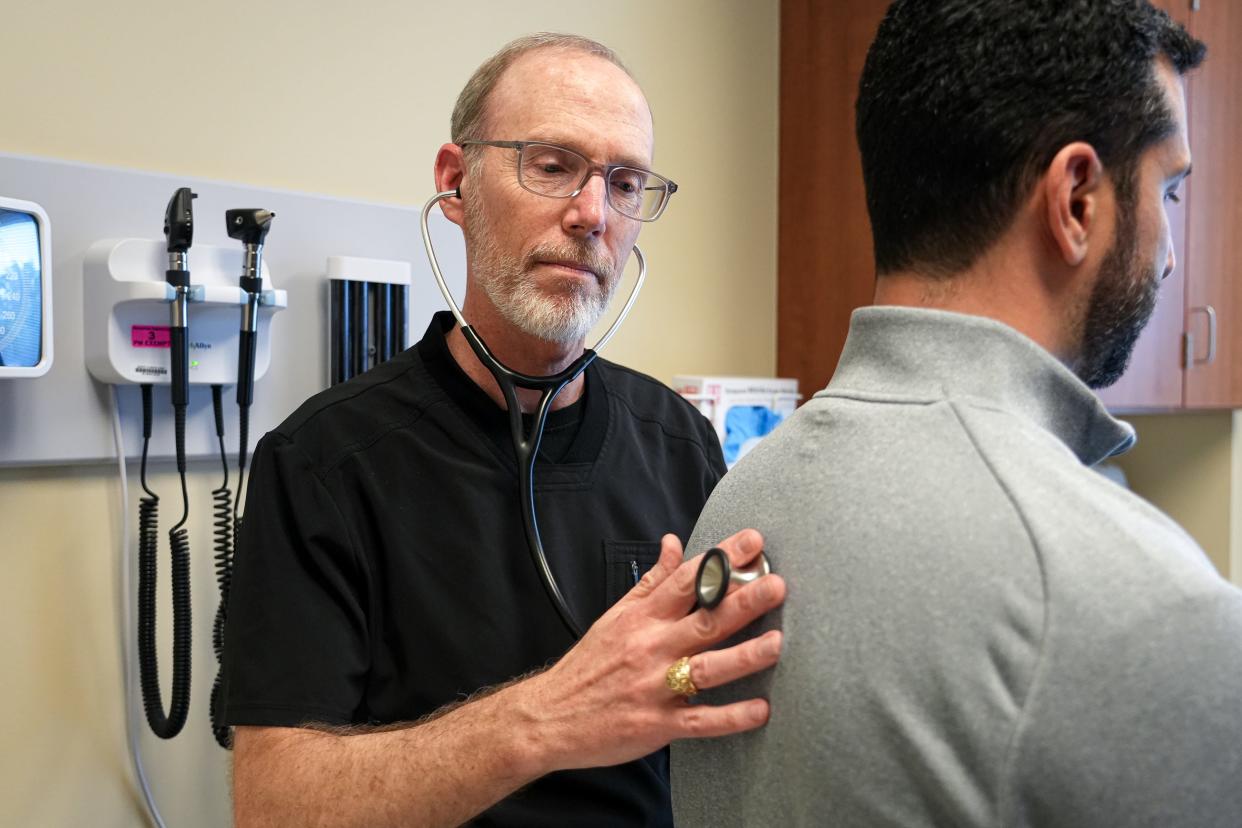

Dr. Christopher Stewart remembers that day, June 20. He was in his office at the Baylor Scott & White Clinic in Cedar Park and preparing to see a patient.

And then he became the patient, with a worsening ache deep inside his chest.

"I was in denial like all my patients," he said.

The symptoms did not mirror some classic signs of a heart attack: no radiating arm pain, no shortness of breath. Stewart, now 54, lacked other risk factors: no high blood pressure, never smoked, no high cholesterol, no obesity, no family history.

But then he was getting lightheaded and short of breath, and the chest pain worsened.

Heeding the heart attack warning signs

Stewart asked for help to get to the Baylor Scott & White emergency room rather than try to walk over, so he could avoid a head injury if he fainted. His EKG revealed he was having a heart attack, in the left anterior descending artery, the one that, if blocked, causes the heart attack known as "the widowmaker" because of the likelihood of death.

Stewart's left anterior descending artery was 99% blocked.

Then he went into cardiac arrest.

After heart attack, Ron Oliveira learns how to change his life at St. David's cardiac rehab

Lifesaving anyone can do

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation to keep his blood flowing and a defibrillator to shock his heart back into rhythm saved him.

"You saved my life," he told the hospital staff.

"It was a huge moment for me," Stewart said. "I've seen these things go the other way."

Medics transported him to Baylor Scott & White Medical Center-Round Rock, where doctors inserted a balloon angiogram to reopen his artery and placed a stent to keep the artery open.

"I felt so good," Stewart said after the stent.

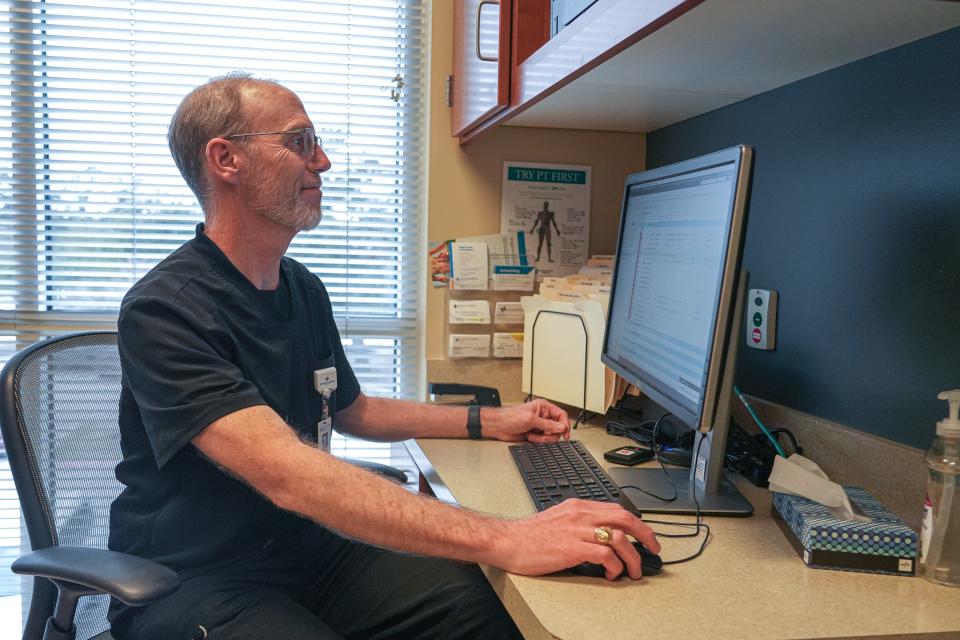

He opted to leave the intensive care unit after two days and lean on his daughter, training to be a physician's assistant, to help care for him at home. After four weeks of intensive cardiac physical therapy rehabilitation, Stewart, a family physician, returned to the office to see patients.

Here is the advice he now gives others:

10 things to know about a heart attack

Learn CPR.

Stock your workplace, your church, anywhere you gather with an automated external defibrillator, know where it is, and know how to use it.

Get your annual well check and stay current on preventions.

Get a heart calcium score. The test done by CT scan is not covered by insurance unless you have risk factors. It's $100 and can spot calcium build up in the arteries. It could have revealed his clot.

Know the classic heart attack symptoms: pain, pressure, aching, tightness or squeezing in the chest; pain that spreads to the shoulder, back, neck, jaw, teeth or upper belly; a cold sweat; fatigue; heartburn or indigestion; lightheadedness or sudden dizziness; nausea; shortness of breath.

Listen to your body. If something doesn't feel right, get checked out immediately. Women tend to have more nausea or shoulder pain than heart pain. People with diabetes might not feel a high level of pain. "Any pain that is not going away, go to urgent care or the emergency department," said Stewart's cardiologist, Jose Condado Contreras, of Baylor Scott & White.

Don't drive to the emergency room. Time is important, and quick medical care can help save heart muscle. Call 911. If you are really close to the ER, have someone drive you.

Eat healthfully, exercise, control cholesterol and high blood pressure., quit smoking, and limit alcohol. Condado Contreras recommends a Mediterranean diet and limiting salt to less than 2,000 milligrams a day. For exercise, do 30 to 60 minutes three to five times a week. The goal: to get your maximum heart rate to a target of 220 minus your age, so 170 beats per minute for a 50-year-old. He recommends stationary bikes and pool exercises as people get older.

Know your risk factors and your family's history.

Enjoy life. Take vacations. Spend quality time with friends and family. Improve work-life balance.

Marking American Heart Month

February is American Heart Month, a time when all people are encouraged to focus on their cardiovascular health.

Coming Tuesday: Can I drive myself to the hospital? Know when to call 911.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: What Cedar Park Dr. Christopher Stewart learned from his heart attack