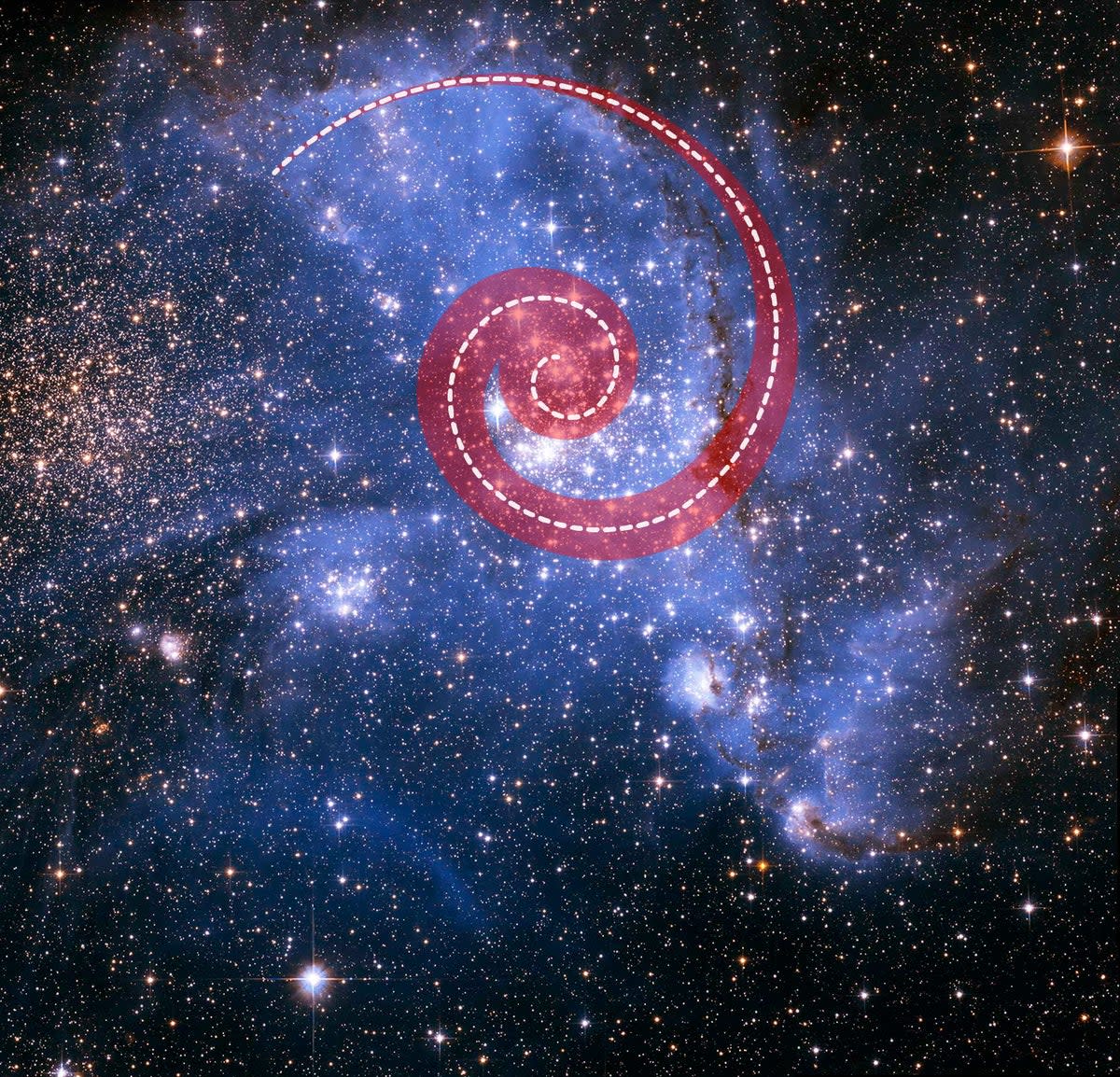

A dense stellar nursery may feed on a spiral of stars, scientists say

A dense engine of star birth in a nearby galaxy may be fed by a spiral of stars.

That’s according to new research conducted with the Hubble Space Telescope and European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope focusing on a dense star cluster in the Small Magellanic Cloud, a dwarf galaxy relatively near our own Milky Way Galaxy. The researchers found the outer spiral arm of stars, gas and stars in a massive star cluster known as NGC 346, appear to be spiraling in toward the center of the cluster, feeding the birth of newborn stars there.

The findings were published Thursday in The Astrophysical Journal.

“A spiral is really the good, natural way to feed star formation from the outside toward the center of the cluster," Peter Zeidler, a postdoctoral researcher at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STSci) in Baltimore, and one of the researchers behind the study, said in a statement. "It's the most efficient way that stars and gas fueling more star formation can move towards the center."

This efficient fueling could explain why NGC 346 births so many young stars. Although the star cluster is only 150 light years in diameter — the Milky Way, by contrast, is 100,000 light years in diameter — it is as massive as 50,000 Suns.

STSci star formation scientist Elena Sabbi led the study, which used the Very Large Telescope and Hubble to track stars in the spiral arm of NGC 346 for 11 years, which allowed researchers to discover their inward spiraling motion. They found the stars move an average of 2,000 miles per hour, covering about 200 million miles — or around twice the distance from the Earth to the Sun — in 11 years.

Astronomers like studying star formation in the Small Magellanic Cloud in part because its chemistry resembles that of the very early universe, a period about two to three billion years after the Big Bang when the cosmos was cranking out new stars at a fantastic rate.

“Stars are the machines that sculpt the universe. We would not have life without stars, and yet we don’t fully understand how they form,” Dr Sabbi said in a statement. “We have several models that make predictions, and some of these predictions are contradictory. We want to determine what is regulating the process of star formation, because these are the laws that we need to also understand what we see in the early universe.”

While the Small Magellanic Cloud is relatively close to the Milky Way on an intergalactic scale, it is still 200,000 light years from Earth. To make more accurate readings of the motions of the stars in the spiral, scientists plan to use additional Hubble observations along with observations by the newly operational James Webb Space Telescope, which should be able to resolve images of lower mass stars than Hubble.