Des Moines museums offer opportunity to explore Black soldiers' sacrifice: 'Valor never expires'

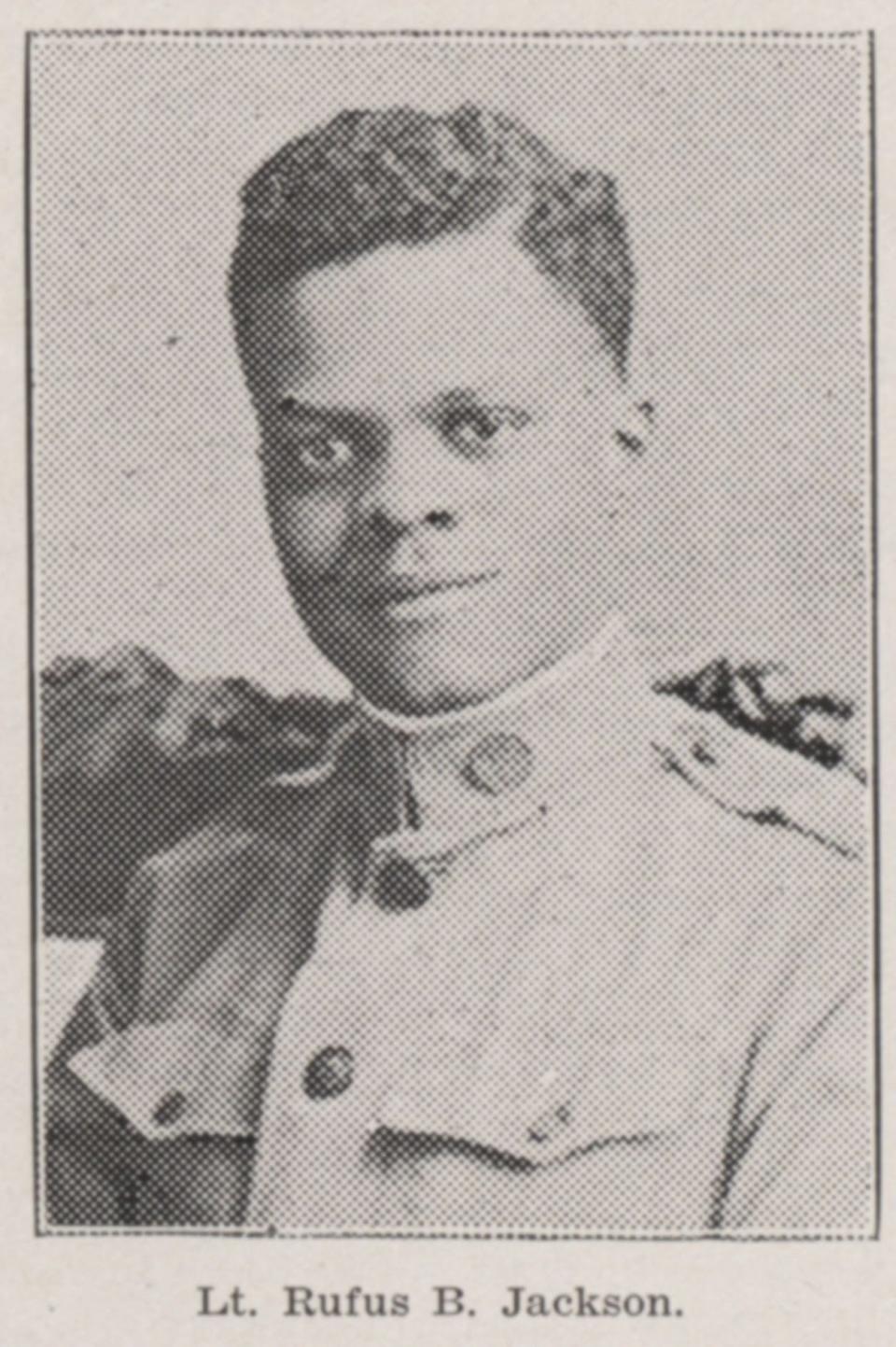

Under a hail of gunfire on a French battlefield in World War I, 2nd Lt. Rufus Jackson of Des Moines crawls forward among the muck and the bodies of his fallen comrades to pinpoint the location of German machine gun nests that are slaughtering his men.

For his selfless heroism that day, Jackson was awarded a Distinguished Service Cross. But a team of military historians believes his valor in action fits the criteria for a Medal of Honor, the highest honor bestowed by the American military. He was denied that medal, the team believes, because of the racial discrimination of the times.

Iowa Columnist Courtney Crowder tells the story of Jackson’s bravery and of the work of the Parkville, Missouri-based George S. Robb Centre for the Study of the Great War. Its team of researchers is conducting a congressionally sponsored valor medals review to determine whether World War I soldiers were unjustly denied appropriate medals because of racial, ethnic or religious discrimination.

Courtney also expertly weaves in the story of another Iowan and Army veteran, Josh Weston, 32, who’s part of the medals review team. Weston, who served as a military police officer, has struggled with depression but has found renewed purpose in endeavoring to ensure that soldiers who served a century ago receive the honors they deserve for their heroism.

Throughout our state’s history, tens of thousands of Black Iowans and people from other minority groups have served in the military with distinction, only to at best blend quietly back into civilian life without recognition of their sacrifice, or worse, endure discrimination or outright attacks in the country they defended.

If you’re interested in learning more about these soldiers’ lives and contributions, Des Moines offers two great places to start: the State Historical Museum, and the Fort Des Moines Museum and Education Center.

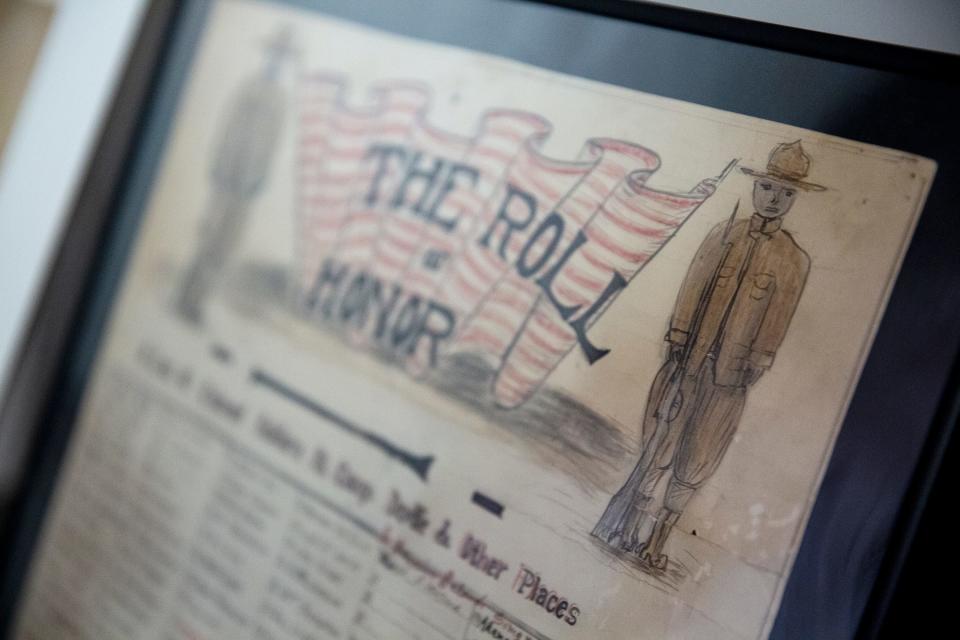

Artifacts on display at the Historical Museum, 600 E. Locust St., include a World War I “Roll of Honor” poster that lists 150 Black Iowans who served, including Jackson. You can also see the Civil War flag from the 1st Colored Regiment of Iowa, which was made by Black women from Keokuk and Muscatine. Or you can dip into the State Historical Society of Iowa’s digital collections. On its Flickr page, an “Iowa and World War I” album includes four photos of soldiers from the Meskwaki Nation and images of Black officers at Camp Dodge.

If you visit the Fort Des Moines Museum, 75 E. Army Post Road, you’ll walk in the footsteps of history. The fort is where, in 1917, this country for the first time gathered a group of Black men for training to become officers in the U.S. Army. According to the Iowa Department of Cultural Affairs, 639 men graduated as newly commissioned captains and lieutenants that October. They shipped out in June 1918, headed to France to fight on the front lines in World War I.

When the war ended, this first wave of Black officers did not leave their leadership skills behind. James B. Morris became a lawyer in Des Moines and for nearly 50 years published the Iowa Bystander, a renowned Black newspaper. He and another Fort Des Moines-trained officer, Charles Howard, a Drake University Law School graduate, founded the National Bar Association, the nation’s oldest and largest organization of Black lawyers and judges.

“They learned leadership, and they came back and used leadership,” said Kathleen Murrin, board secretary of the Fort Des Moines Museum and Education Center.

Matthew Harvey, president of the board and a former Army lieutenant colonel who served in Afghanistan, said “all Black officers can trace their history” to the officers trained at Fort Des Moines.

In World War II, the fort further cemented its prominence in U.S. history when it became the nation’s first Army training center for women, preparing more than 70,000 members of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps.

“We feel like it’s important for everyone to appreciate that all of this happened in Des Moines, Iowa,” Harvey said.

The museum, operated entirely by volunteers, is open from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Saturdays. Visits are also possible by appointment if a volunteer is available. Check the museum’s Facebook page for updates. Harvey said the museum is seeking donations to allow resumption of school tours.

I thank the volunteers for their work to highlight the fort’s role in this nation’s ongoing march toward racial and gender equality. I’m also grateful for the work of the valor medals review researchers to ensure the bravery and sacrifice of all soldiers receive their just, long overdue recognition.

As Weston so aptly puts it, “valor never expires.”

Carol Hunter is the Register’s executive editor. She wants to hear your questions, story ideas or concerns at 515-284-8545, chunter@registermedia.com, or on Twitter: @carolhunter.

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: Iowa museums honor Black soldiers' sacrifices in wars