DeSantis blew a chance to prove the Everglades are more important than roads | Editorial

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

For all of Gov. Ron DeSantis’ appalling political stances — from making it harder to vote by mail to picking a fight with the cruise industry over “vaccine passports” — he’s consistently been on the right side of one issue: protecting the Everglades.

That’s why it’s mystifying that a governor who based a great part of his campaign on water quality just cleared the way for a road to be built over wetlands critical for an Everglades restoration project that DeSantis himself has championed.

On Tuesday, DeSantis and the Florida Cabinet rejected a judge’s ruling that the planned extension of 836/Dolphin Expressway violates Miami-Dade County’s development rules to protect water supply, agriculture lands and wetlands. Commissioner of Agriculture Nikki Fried was the only Cabinet member who voted to uphold the judge’s decision. Chief Financial Officer Jimmy Patron and Attorney General Ashley Moody voted with the governor.

Luckily, DeSantis and the Cabinet’s decision isn’t the end of the road — no pun intended — for the environmental groups that challenged the highway extension. Tropical Audubon, one the plaintiffs, has vowed to appeal the case, and state agencies still have to grant environmental permits for the project.

‘Meager’ improvements

Even DeSantis recognized that approval of those permits is not a given, saying that it would be “premature” to guess how what the South Florida Water Management District will decide. But he opted to not stop the project “at the front end” and before the permitting process takes place.

We understand the governor’s desire to allow the state’s environmental agencies — and not politicians — to determine whether the 836 extension is compatible with Everglades restoration and to not derail a road project that was approved by local elected officials.

But we also know DeSantis has not been afraid to be heavyhanded and use both his bully pulpit and executive power to force change — for example, telling locals what they can or cannot do when it came to COVID-19 restrictions.

Perhaps the governor didn’t feel strongly about the 836 extension’s detrimental impact to the environment. Or perhaps he thought the environmentalists challenging it didn’t make a strong case. But a judge who sat through hours of testimony and evidence did and ruled last year that the traffic improvements to West Kendall would be “meager” and the road would threaten Everglades restoration.

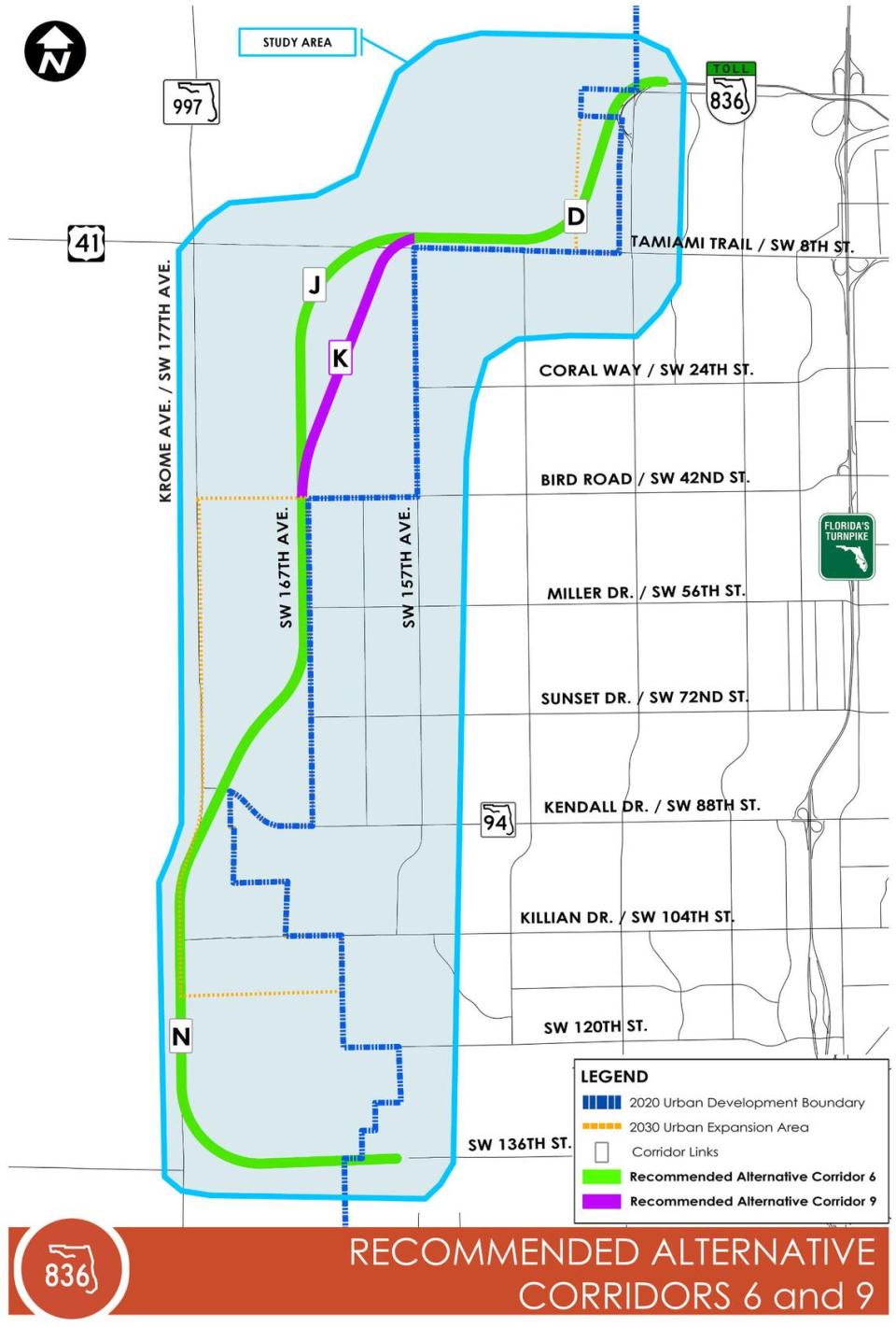

The 14-mile extension, dubbed Kendall Parkway, would run south from where State Road 836 currently ends at Northwest 137th Avenue and connect it to Southwest 136th Street. For that to happen, the County Commission in 2018 allowed the planned road to go outside the county’s Urban Development Boundary, which protects agricultural and environmentally sensitive lands from encroachment. The road would be built over the Bird Drive Basin and the Pennsuco wetlands, which are key to guaranteeing drinking water for Miami and the Keys, environmentalists say.

Plaintiffs who filed a challenge to the County Commission’s decision argued it violated Miami-Dade’s comprehensive plan, which stipulates the county must discourage the proliferation of urban sprawl, direct incompatible “future land uses” away from wetlands and prioritize the implementation of the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan, known as CERP.

Development inevitable

On the topic of “urban sprawl,” we would be fools to believe a new road wouldn’t spur more urban development along the western edges of Miami-Dade abutting the Everglades. The County Commission tried to prevent that from happening by prohibiting developers from using the new expressway in traffic calculations for future projects. But nothing stops big-pocket builders from pressuring future county commissioners to waive that rule with a two-thirds vote once the highway is up and cars are running.

The county’s own traffic expert testified during court proceedings that the average driver would save an estimated six minutes on a two-hour round-trip commute from West Kendall to downtown. Miami-Dade County’s attorney argued on Tuesday that the projection didn’t paint the whole picture and that some specific segments would see double-digit improvements.

But the uncertainty of those traffic improvements poses an important question: Are they certain enough to justify building a $1 billion road over land needed to restore the River of Grass?

Unless environmentalists can stop this project, we will find out the answer to this question after this boondoggle is built.