‘You deserve to be remembered.’ WWII soldier who resisted Jim Crow in Durham honored.

The story of Pvt. Booker T. Spicely had pretty much been forgotten.

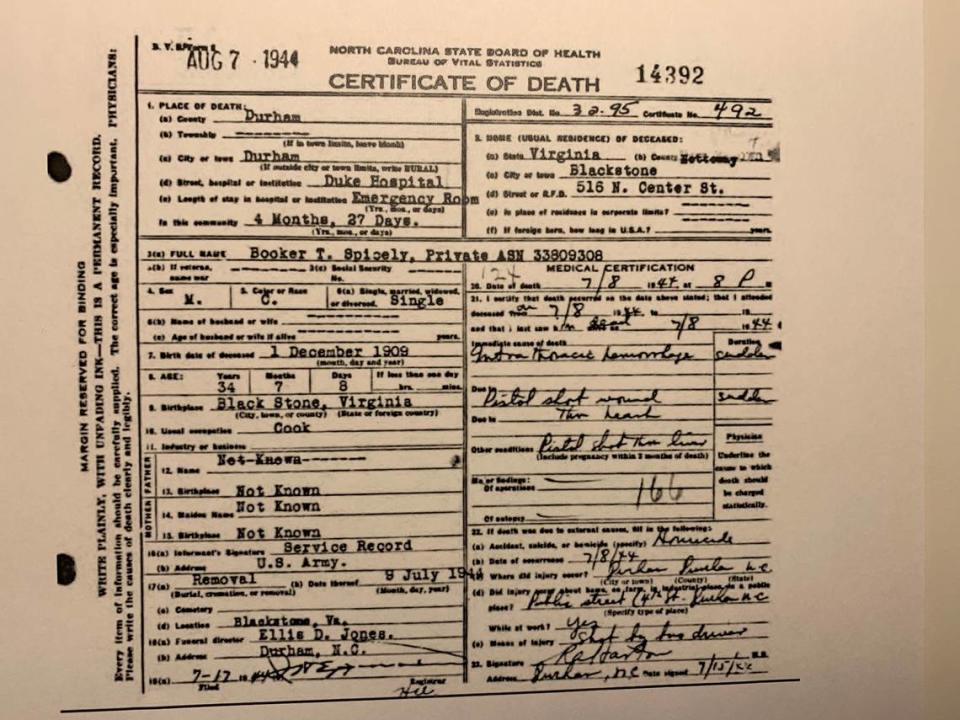

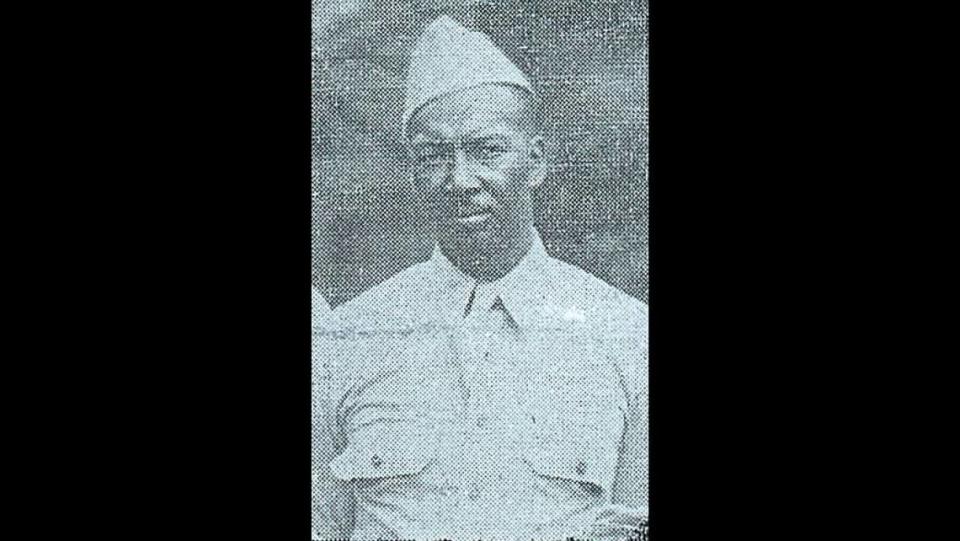

Few in Durham had heard of how a U.S. Army soldier in uniform, a Black man from Philadelphia training at nearby Camp Butner during World War II, questioned the driver who asked him to move to the back of a bus when several white soldiers got on. Or of how the white driver fatally shot the soldier and left him lying on the side of the street as he finished his route.

Even some members of Spicely’s family were only vaguely aware of his story, if at all.

“My mom just said one thing: ‘You had a cousin that was shot by a bus driver.’ No details, no nothing,” said Cynthia Mitchell of Midlothian, Virginia. “I guess you just don’t focus in on stuff like that. You just keep moving. You just keep going forward.”

But it’s easier to move forward if you know where you’ve come from and what those before you went through. That’s part of the thinking behind a state highway historical marker unveiled Friday afternoon two blocks from where Spicely was shot on July 8, 1944.

Mitchell was one of more than 20 members of Spicely’s family who helped pull the cover off the marker at Broad Street and Club Boulevard and then posed for photos with it. They were joined by dozens of others, including politicians, clergy and members of a committee that documented Spicely’s story and pressed the state for the marker.

The head of the committee, James Williams Jr., likened Spicely to better-known civil rights heroes such as Rosa Parks, who was arrested for refusing to move to the back of a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, 11 years after Spicely was killed.

Williams, a retired public defender for Chatham and Orange counties, said Spicely was also emblematic of the Double Victory or Double V campaign during the war. Named by the Pittsburgh Courier, an African-American newspaper, it gave focus to Black soldiers who were fighting fascism abroad while also fighting for freedom and equality in their own country.

It was that spirit, Williams said, that prompted Spicely to initially resist the bus driver Herman Lee Council.

“Here’s this soldier in uniform, who’s supporting this country’s war efforts, and he asks these reasonable and sensible questions,” Williams told those gathered at the marker. “’Am I not wearing the same uniform as those white soldiers? Do I not run the risk of stopping a bullet just like those white soldiers? Why are you treating us like this?’”

Council was arrested and charged with murder. Duke Power Company, which owned and operated the bus, put up the bail money that allowed Council to continue working until his trial two months later and also provided his attorneys. After a full day of testimony from witnesses, an all-white jury took 28 minutes to declare him not guilty.

A historical marker that breaks new ground

The state has put up more than 1,600 highway historical markers since 1935, through a program run jointly by the Department of Transportation and of Department of Natural and Cultural Resources. The Spicely marker is the first to include the phrase “Jim Crow,” the system of laws, rules and customs that long enforced racial segregation and oppression.

Reid Wilson, the secretary of Natural and Cultural Resources, told the gathering that there will be more markers that highlight events from the Jim Crow era.

“A lot of North Carolinians are not aware of this history,” Wilson said. “Which underscores why it’s so important that we’re here today and we unveil this marker which will stand for decades and decades. We need to understand and commemorate the people and the events that have shaped our lives and who we are as a state.”

The marker, which condenses Spicely’s story to six short lines, mentions that his death helped revitalize the NAACP, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. The Durham branch of the organization was named for Spicely that summer.

But his name was dropped sometime later, says B. Angeloe Burch Sr., the branch president. Somehow even the NAACP forgot about Spicely, Burch said.

“We lost our own history,” he said, adding that the branch will seek to restore Spicely’s name. He said putting the story on a cast aluminum marker for all to see will keep it alive.

“We write it down so our youth can see it and begin to ask questions,” he said.

Scott Ellsworth called the marker’s unveiling a new beginning. Ellsworth, a Duke University graduate and writer from Michigan, helped uncover Spicely’s story in his 2015 book The Secret Game, about a basketball game played clandestinely between the all-Black team at N.C. Central College for Negroes and an all-white military team from the Duke medical school.

“We don’t know what the legacy of Booker Spicely is going to be yet,” he said. “The people that he affected back in 1944 — and he had a great effect on them — most of those folks are long gone now. And now this is a second chance for us here in North Carolina, a second chance in America, to try to face the portions of our past that we need to know to understand the present.”

Where to learn more about Booker Spicely

Each state historical marker is backed by an essay online that tells the fuller story. Spicely’s can be found at ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=G-141.

There’s also a guide with newspaper clippings, letters, government documents and other primary sources that North Carolina teachers can use in their classrooms. It was developed for grades 8 through 12 by Carolina K-12, a program of the UNC-Chapel Hill’s Carolina Public Humanities program.

It’s important that students be taught the good and the bad in their country’s history, said Christie Norris, the program’s director.

“My grandfather always told me, when I made a mistake, you learn from it,” Norris told the gathering Friday. “When you know better, you do better. So when students learn not just about the triumphs of America but also the struggles — when they analyze what we got wrong and what we got right — it’s this examination of the full picture that helps them do better.”

Why is the marker where it is?

Spicely was shot at the intersection of West Club Boulevard and what is now Berkeley Street in the Walltown neighborhood. The historical marker stands three blocks west at Club and Broad.

The reason is that markers in North Carolina’s program must be placed along state highways. Neither Berkeley nor that stretch of Club Boulevard are state-maintained roads, but Broad Street is.

But the location resonates for another reason, says Williams, head of the Booker Spicely committee. The marker stands on the edge of the campus of the N.C. School of Science and Mathematics, which occupies what in 1944 was Watts Hospital. Military police took the wounded Spicely to Watts, but he was refused care because of his race. He died shortly after arriving at Duke Hospital farther away.

Spicely’s actions that day took courage, said Williams.

“And so the least that we can do — and I don’t say it to minimize it, because it is important — is to erect a state historical marker in his honor,” he said. “And to say that we, in the city of Durham and Durham County and the state of North Carolina, we honor you, we appreciate your sacrifice, and you deserve to be remembered.”