The desperate, persistent need for childcare

On any given weekday, Kathi Barton can be found doing what she loves most.

Between the good mornings and breakfast, learning through play, first snack, outdoor time, lunch, reading time, nap time, second snack, cross-town commutes, the thank yous and goodbye for nows, she finds a unique kind of joy.

Her quaint home in a quiet Salina neighborhood is the stomping grounds for around 10 toddlers this spring. This summer, it will be 12.

It’s not exactly a job that comes with serenity. And it’s definitely not for everyone, she says. But it’s one with purpose, and that’s always been enough.

“We really try to be that home away from home for these kiddos,” Barton said.

Kathi and her husband Curt own and operate Eagle Wings Daycare Home, one of 121 at-home licensed daycare providers in the county.

Throughout her more than 35 years as a professional childcare provider, Kathi Barton has lived her fair share of challenges. But her usual waiting list has never been quite so long.

In Saline County, like much of the nation, childcare availability is diminishing for families. Barton doesn’t like turning people away, but she’s only licensed for so many children.

“With a waiting list a mile long, we get people who call in tears, crying that they can’t find anybody,” Kathi Barton said. “They just don’t know what to do.”

Childcare desert drives out families from local workforce

As of early 2023, there are an estimated 1,000 to 1,500 fewer available childcare spaces than needed in Saline County, according to data from Childcare Aware, a statewide resource and referral agency.

Meanwhile, local childcare centers and at-home providers alike are operating at capacity. While at-home providers face their own unique challenges, care facilities are having trouble hiring staff due to poverty-level wages, among other issues.

The shortage has been in a crisis state since before the COVID-19 pandemic, but the ongoing financial impacts from 2020 to 2022 have forced more at-home providers to cease operations. Others are holding onto emergency grants to sustain their daycares, but most of those funds will dry up later this year.

For those in Saline County, low childcare availability has had a domino effect, of sorts, resulting in a gradual exodus of people from an otherwise growing economy.

And more often, the childcare shortage has become a part of a three-headed monster for economic development in the greater Salina area. A lack of housing, childcare availability and stagnant wages have driven families out of the county even after some secured jobs in the area.

The weight of the issue has infiltrated conversations among state and local governments, employers and childcare providers alike, who are looking at ways to expand and improve childcare services availability.

“It’s a national fix, and I don’t know that we will see it in my lifetime,” said Leigh Ann Montoy, childcare licensing coordinator with the Saline County Health Department.

Montoy and her team get a first-hand look at the childcare provider shortage as the regulatory agency for childcare licensing in Kansas.

Among issues like financial constraints and lack of time and other resources, burnout has been a large part of what her agency sees in childcare providers.

“It’s extremely demanding work, it’s physical work, it’s challenging work,” Montoy said. “And people are doing all that for very low wages – poverty-level wages.”

On the state level, the Kansas Legislature began a divided debate on how to provide easier access and availability to childcare which resulted in House Bill 2344.

Before Kansas Governor Laura Kelly vetoed the bill April 19, its proponents argued the scarcity of childcare spots was due to crippling regulations shutting out would-be providers. Opponents of the bill blamed it primarily on low pay leading to not enough childcare workers.

More: How safe is too safe? Kansas lawmakers want to tackle child care regulations

“This bill would reverse the progress we’ve made toward that goal, loosening safety requirements for childcare centers and preventing the state from being responsive to individual communities’ needs,” Kelly said in a statement regarding HB 2344. “While I agree it’s time to review our childcare policies, we must do it together – and in a way that improves, not harms, our state’s ability to help families and keep kids safe.”

Representative Daniel Hawkins, a supporter of HB 2344, also issued a statement after the veto.

“One of the biggest issues facing Kansas families is a lack of child care options,” Hawkins said in his statement. “Governor Kelly’s veto reinforces the failed status quo by choosing overregulation over workable solutions.”

A home away from home

Kathi Barton didn’t know, exactly, how to feel about the proposed legislation. But she said she knew one thing for certain – lawmakers weren’t getting the full picture.

“I would challenge any one of them to spend a day and watch what I do, and be with these kids all day,” Kathi Barton said. “Then, they would have a different perspective on what actually happens.”

All of Kathi and Curt’s children are college-aged and older, but their yard is still filled with playsets, swing sets and toys. It’s been a couple decades since they have celebrated a newborn, but Kathi’s home is still fitted with a baby pin and changing station.

Their mornings start around 6:45 a.m. and their days end around 6 p.m. But that’s just time spent with the kids. Most workdays, including cleaning, cooking, shopping, commuting, budgeting and other unseen tasks add up to 10- to 12-hour days.

“When we first started, we’d work until midnight a lot of times,” Curt Barton said.

As an at-home provider, the Barton’s wages are a direct relation to how many children they have, what they charge and what their overhead expenses are.

If you break it down to how many hours a week at home providers work, Montoy said, most would by and large make well below minimum wage – sometimes $6-8 per hour.

For the Bartons, it’s never been about the money. Kathi knew she wasn’t entering a profession that would make the big bucks. But financials are an ever-present stressor for providers today.

Kathi and her husband are not simply babysitters, she said. Their roles encompass so much more; every detail of their unwritten job descriptions couldn’t fit into this report. They change daily to fit children’s needs.

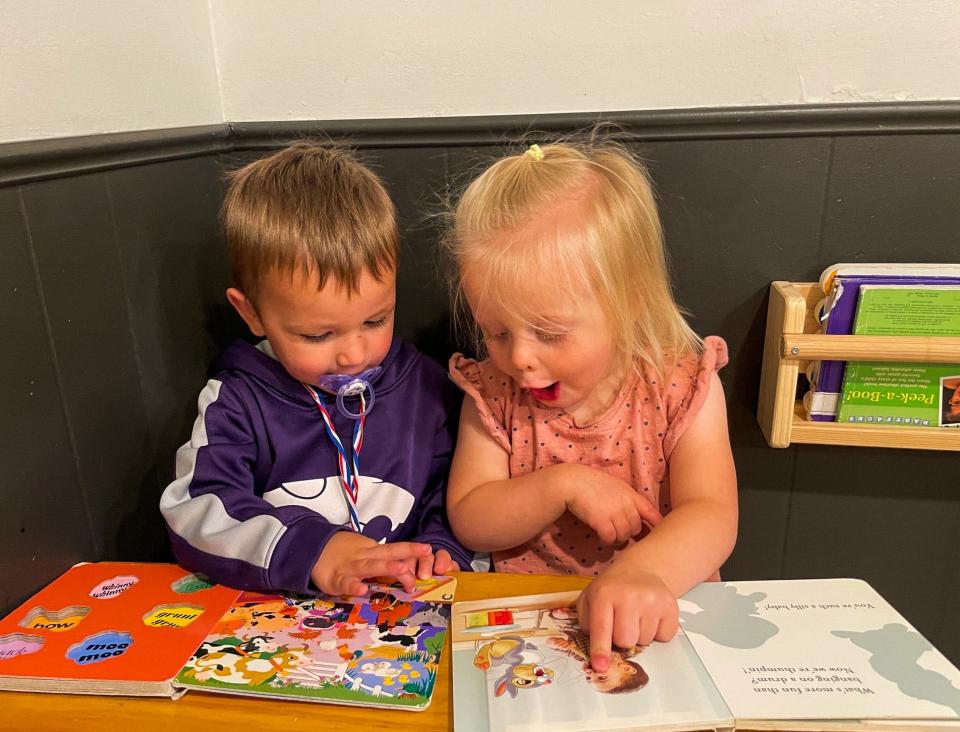

At Eagle Wings, Kathi and her husband focus on learning through play, social emotional lessons, and make an intentional point to foster strong literacy skills. Children not quite two years old can tell you what an author and illustrator’s roles entail.

The daycare even has its own YouTube page titled “Storycast Munchkins” with videos of Kathi Barton reading her favorite children’s books. The videos show her expressive reading as a young, captivated audience giggles and plays along in the background.

On the good days, the vocation of fostering young lives outweighs the pressures of inflation, of a $450 per week grocery bill, and of the “sane” thing to do – getting a job that pays more and comes with a better health insurance plan.

And on the bad days, another childcare center like hers closes up shop, leaving more families without an answer.

What can be done about childcare locally?

Some momentum has begun to pick up in addressing the childcare shortage in Saline County. With more entities amplifying the issue, nonprofits and local government are working to come up with ways to use funds for sustainability.

At the end of April, the Salina Area United Way announced the start of its Early Childcare Initiative fund.

The first step in the nonprofit’s childcare initiative is to increase wages across existing centers in Salina. Centers in the community are currently paying childcare staff at poverty-level wages, according to data from Childcare Aware of Kansas.

The goal of the initiative is to raise funds to increase wages at facilities to a living wage, which has been found by the Salina Area Chamber of Commerce to be $15 an hour. Nonprofit centers will have the ability, once funds are raised, to apply for sustainability grants to combat the existing wage gap.

“Wages have been pinpointed as the number one critical piece as to why we’re struggling to retain childcare workers and keep rooms open at centers,” said Claire Ludes, Executive Director of the Salina Area United Way, in a release. “How can we expect to gain quality staff in local childcare centers at a poverty level wage?”

The intent and focus of recent local childcare initiatives is focusing how to expand upon existing licensed providers and care centers. While creating a new facility has been briefly discussed by local officials, it would be a costly proposal when taking into account sustainability and the persistent staffing issues.

Similarly, Saline County has designated some of its American Rescue Plan Act funding to go toward childcare. The county has had its own struggles with hiring staff due to the lack of childcare for families who would otherwise consider a move to the county for employment.

But how, exactly, to use those funds has been a head-scratching conversation for the county’s board of commissioners and department heads.

"That would be a role that 25 years ago, county governments would say 'you're concerned with childcare?'" said County Commissioner Monte Shadwick at a meeting earlier this year. "But it's a big deal now."

Other local initiatives have included business-to-childcare facility partnerships that work to increase wages at care centers. One example of this is Salina Regional Health Center’s partnership with Salina Childcare to provide workers with livable wages and hospital employees access to that childcare.

In the short term, Montoy said the best way to fill the childcare void is promoting, encouraging and supporting home childcare. In Kansas, at least, that’s where the bulk of young children are cared for during the day.

“(At-home childcare) can be isolating, it’s lonely, and they just don’t have that backup and support that most of us have in our work environments,” Montoy said.

Kathi Barton knows those feelings all too well.

But just as isolating as it is, it can be rewarding, she said. Barton has even offered to mentor and help others interested in starting an at-home daycare.

The job is not one that comes with serenity, but it has its perks, she said. Perks like seeing a former student for the first time in a long time who grew up to be an engineer, a fighter pilot, or a fellow educator. Perks like the “lightbulb” that goes off when a kid with a speech disability masters a problem vowel.

“Providers touch the lives of those who build the future,” Kathi Barton said. “If you’re doing it right, you’re hopefully shaping future generations to do the right thing, go in the right direction and be kind to other people.”

Last Thursday, Curt Barton set up a sprinkler system in their backyard for the upcoming warmer days spent outside. As Curt walked toward the hose, five toddlers huddled around him.

He turned over the spigot and a light mist drifted through the cool morning air. The children, not quite tall enough to reach the hose, raised their hands toward the mist, laughing and jumping enthusiastically.

A rainbow formed between them, and behind it, a young girl smiled.

Maybe, a future pilot, educator or engineer.

Kendrick Calfee has been a reporter with the Salina Journal since 2022, primarily covering county government and education. You can reach him at kcalfee@gannett.com or on Twitter @calfee_kc.

This article originally appeared on Salina Journal: The national childcare crisis reflected in a Kansas community