Despite the High-Profile Heist, Maurizio Cattelan’s Blenheim Palace Exhibition Remains as Shocking as Ever

Blenheim Palace, a UNESCO-protected stately home in the sprawling green hills of Oxfordshire, England, has seen many things in its 300-year history. For one, it was the birthplace and dwelling of Britain’s wartime prime minister Sir Winston Churchill, and has thrice hosted decadent fashion shows by the house of Christian Dior. In recent years it has opened its doors to the worlds of modern and contemporary art thanks to Churchill’s heir Edward Spencer-Churchill, founder of the Blenheim Art Foundation, which he established in 2014.

So far Spencer-Churchill’s approach has been singular: large-scale solo shows by renowned international artists, whose work both responds and reacts to the opulent surrounds of the 18th-century palace. Ai Wei Wei opened the program five years ago, followed by Lawrence Weiner, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Jenny Holzer, and most recently the works of the late Yves Klein. Curated by the foundation’s director Michael Frahm, the sixth show opened Thursday featuring both newly commissioned and cult works by the Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan—and despite the competition, it may prove to be its most provocative yet. Dotted around the palace’s principal halls and its garden, 13 works large and small converse not only with Blenheim’s baroque architecture but also with Britain’s tenuous political climate in anticipation of Brexit—starting with an intersecting fabric walkway at the palace’s gate emblazoned with the repeating pattern of the Union Jack flag. Demarcating the palace’s main thoroughfare, the fabric path will weather all that autumn rains and muddy boots can stomp into it, in a radical statement on British (read: world) politics by the artist.

"There are people in the U.K. who may find visiting stately homes representative of a class system and other things that are bygone. This is about breaking down these sorts of cultural barriers," Spencer-Churchill tells AD. "My job is not to censor, it is to enable. Some people may not like all of the pieces Maurizio has put in, but if I can enable a debate, then we are only richer for it.”

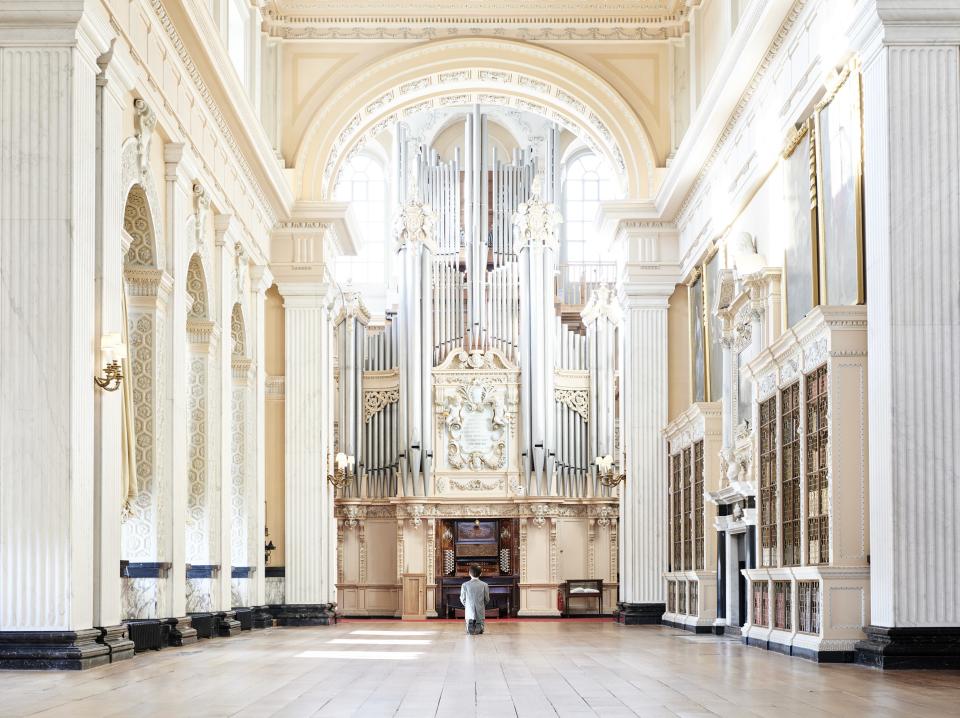

Titled “Victory Is Not an Option,” Cattelan’s show raises a multitude of prickly questions and dredges up collective memories of wartime horrors. One historical near-miss in particular is present in the form of the sculpture Him, 2001, installed inside the Long Library, which depicts the childlike form of Adolf Hitler kneeling in supplication before the palace organ. “Clearly, that piece is very provocative. There are rumors that he wanted to take Oxford as his capital and use this place as his house. It was obviously the family home of his foe, so I think there is a certain eloquence to him kneeling in forgiveness,” recalls Spencer-Churchill, whilst insisting the Union Jack walkway remains the exhibition’s most controversial inclusion.

Other works in the show provoke as much through their assimilation into the palace’s existing finery as they do in their own right. Replacing an original lavatory in a wooden water closet just outside Churchill’s bedroom, Cattelan’s notorious solid gold toilet, titled America, 2016 (valued at a reported $5 million USD), was presented in working order to the exhibition public, who were offered three minutes each on the gilded throne. That is, until it was discovered to be stolen in the early hours of Saturday morning, after Cattelan hosted a silent dinner party inside the palace during which guests were prompted to communicate with one another via supplied notebooks.

Unplanned (and, as of yet, unsolved) heist aside, there is no lack of remaining grist for Cattelan’s culture shock mill. Dominating the Great Hall, a gargantuan plaster flagpole appears gripped by Joan of Arc’s floating arm—blown up from Frémiet’s golden statue guarding the Tuileries’ Northeast corner in Paris—as the first of several gestures that question representations of powerful historical figures. Later, the fallen figure of Pope John Paul II, struck by a meteorite, matches Blenheim’s crimson carpets; the infamous taxidermy horse Novecento, from 1997, hangs U-shaped from the ceiling; and Disney’s Pinocchio floats lifeless in the palace fountains. Further exploration of the gardens and surrounding alcoves reveal a flock of 200 (also taxidermy) pigeons nestled on every possible perch inside Blenheim’s chapel. At a mere stone’s throw a wooden crate contains another, very different chapel: Cattelan’s 1:6 scale model of the Sistine Chapel transports viewers into a 360-degree Vatican miniature. Despite the swirling religious and historical connotations that link this work with the show, it stands alone in its immersive nature, whilst others uncannily melt into their surrounds. So although the search for the missing golden toilet continues, Blenheim’s visitors will still find an ample serving of satire amongst the family portraits, rare china, and a smattering of Churchill’s own watercolors—whether they like it or not.

Originally Appeared on Architectural Digest