Despite local and national calls to defund police, Louisville didn't. Here's why.

LOUISVILLE, Ky. – New York City shifted $1 billion from its police budget.

Los Angeles' city council approved $150 million in cuts to police.

And Minneapolis officials have pledged to begin the process of ending the city's police department.

But in Louisville — a city in the national spotlight following Louisville Metro Police's fatal shooting of Breonna Taylor — the Metro Council reallocated no city dollars for police.

Council members, in interviews with The Courier Journal, gave a host of reasons for their approach to police funding: low pay, staffing reductions in Louisville Metro Police, rising violent crime, timing and a lack of alternative response models, among others.

Even those open to the idea of shifting some police responsibilities to outside agencies or "co-responders," such as behavioral health specialists, said they were reluctant to move quickly without a plan in place.

"I, and I think many others, would be in favor of using funds in that way," said Councilman Bill Hollander, D-9th District. "But there are no programs in place right now to do that.

"The council did not support 'defunding the police' if that means having fewer officers, without alternatives to deal with the things officers are asked to deal with — mental illness, drug addiction or people without homes."

The council's vote didn't sit well for some who were disappointed to see the police budget grow, not shrink, in the final document, even as a rallying cry for defunding police departments across the country grew among protesters and progressives.

"They really need to look at what is happening in this moment," said Chanelle Helm, an organizer with Black Lives Matter. "They have to listen to people in the streets right now."

Others, like Robert LeVertis Bell, a former candidate for Metro Council who made police funding a focal point in his campaign, were not surprised.

"Anybody who's watched the Metro Council since merger knows that they have been very resistant to social pressure for fundamental changes to the police," Bell said.

July 9: Police interviews say Breonna Taylor's home was a 'soft target,' suspect already located

He added that there's a "lack of vision" on Metro Council, calling it a "go-along-get-along" kind of body.

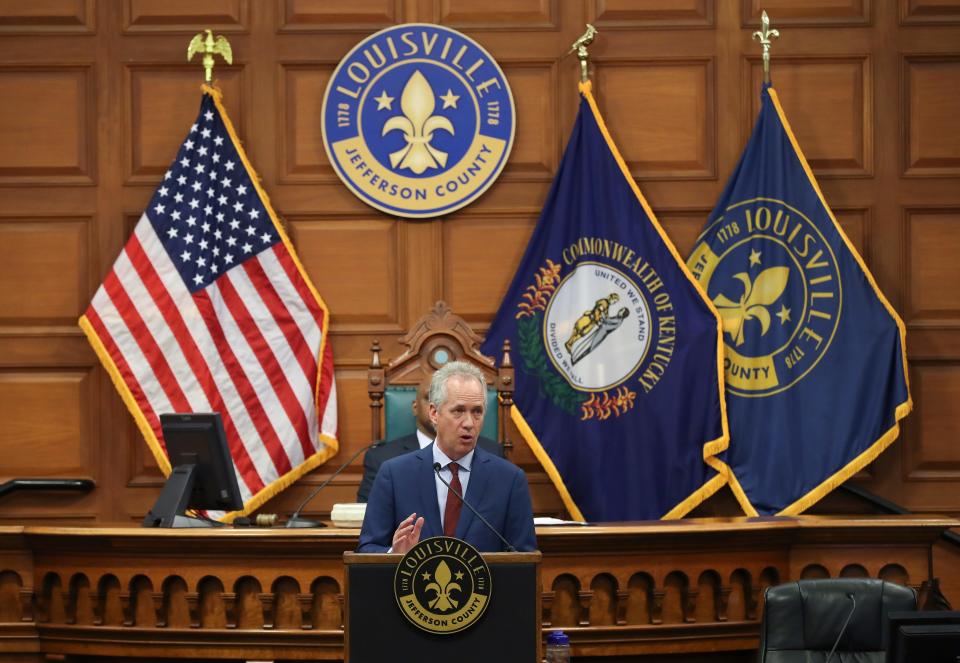

The 26-member Louisville Metro Council has a 19-member Democratic majority led by Council President David James, a former police officer and Fraternal Order of Police president, and Councilman Markus Winkler, the Democratic caucus chairman, who was first elected in 2018.

The budget was ultimately approved with the exception of one no-vote: Councilwoman Barbara Shanklin, D-2nd, who said the spending plan didn't send enough money to her district.

Josh Poe, a researcher with the Root Cause Research Center, a Louisville-based grassroots research organization, called the budget vote a "tone-deaf" stance that shows the council doesn't understand that "the whole world is watching Louisville."

"They're used to doing things in this way that's very isolated, very provincial, without really any context of where they land nationally in these sorts of decisions," Poe said.

Here's what led up to the vote:

A very different police budget conversation

Mayor Greg Fischer presented his budget proposal to the council in late April, jump-starting several weeks of budget hearings prior to the council's final vote on the spending plan in late June.

Then-Chief Steve Conrad appeared before the council's budget committee on May 18, a week before George Floyd's death sparked a national conversation around racial justice and 10 days before protesters first took to Louisville's streets.

At that meeting, the conversation focused more on the potential to increase the police budget, to pay officers higher salaries, than making any cuts.

"We can't go another year without addressing (pay). Full stop," Councilman Anthony Piagentini, R-19th District, said in May, before asking officials about how council would go about budgeting for salary increases. "If we all have to take furloughs to get LMPD paid properly, then we'll start talking about it."

Other council members also expressed concern about LMPD being "outbid" on potential officers by other departments, and Conrad noted that both firefighters and code enforcement officers within Louisville Metro Government earn a higher starting salary.

LMPD provided council with data showing Louisville's base pay for entry-level police employees — about $39,000 — is lower than than several nearby areas.

July 7: Breonna Taylor's mother endures national spotlight to make sure Black women's lives matter

LMPD officials and Metro Council members have expressed concern for months, if not years, over the number of police officers leaving the department due to resignation or retirement.

And a canceled recruit class last fiscal year, amid citywide budget cuts that touched nearly every agency, left the department with fewer officers on the street in June 2020 than a year ago.

"What I fear worse than the mass exodus is the failure of young men and women interested in coming in to be their replacement," Councilman Mark Fox, D-13th, a former LMPD major, said in an interview, calling LMPD "already defunded, demoralized and dejected."

Public outcry demands council 'revisit' police funding

National dialogue shifted in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, as protests swept American cities, including Louisville.

The idea of "defunding" the police, or reallocating dollars into other social programs or community priorities, began to gain traction, and activists in Louisville made a case for it locally.

The city, by that point, had reached national prominence as protesters around the nation called for justice for Breonna Taylor, who was shot to death by Louisville police in March.

Poe said he called for defunding the department last year with "very few voices in that space." From then to now, he said the conversation has expanded widely, showing it's "not going anywhere."

"An entire generation coming up sees it this way," Poe said.

"We've never had a problem defunding all these other programs," said Shawnte West, a social worker who pushed Metro Council to cut the police budget. "Every day the dial turns in other cities, we just look even worse."

Just over a week before the council's June 25 budget vote, Councilman Brandon Coan, D-8th, published a plan to cut LMPD's budget by 15% over the next three budgets.

Coan said he'd tried to negotiate up until the final vote — including suggesting that if people weren't interested in a 5% reduction, just $1 million could be shifted to pay for 10 public or behavioral health specialists.

His efforts got no traction among his colleagues, he said, calling it a "disappointment."

"A large part of the public was so vocal and clear about the need to revisit the police budget," Coan said after the vote. "Council's failure to send any signal that it heard them was really troubling to me."

Ryan Nichols, the president of the Fraternal Order of Police chapter representing LMPD officers, said the idea of defunding the police was "outlandish" from the police's viewpoint: "You should want the best trained and best qualified person to be the police officer for your municipality. ... To get that person, you have to pay that person."

The final version of the budget redirects the agency's state forfeiture funds — about $1.2 million — toward exploring "deflection," the idea of moving people away from the criminal justice system, and the use of co-responders, like behavioral health specialists, along with recruitment efforts and training on using force, de-escalation and implicit bias.

Other changes include:

$3.5 million for a community grocery intended to address a Louisville food desert;

$763,500 set aside for forthcoming civilian review of LMPD, potentially for an inspector general, civilian review board or hybrid model;

$5 million more for the Affordable Housing Trust Fund;

$1 million for a new Homeowner and Rental Repair Loan Fund; and

$2.5 million for programs that support home repair and support home ownership.

After the vote, Hollander told The Courier Journal that increased funding in the budget for disadvantaged neighborhoods was done "in large part because of the racial equity issues that have really risen to the fore."

June 19: Louisville police is firing officer Brett Hankison involved in Breonna Taylor shooting

"The urgency of dealing with some of those issues did change in the last few weeks," he said.

What if there had been more time to examine the police budget?

Some council members in interviews with The Courier Journal appeared to suggest that, had there been more time for public discussion, it's possible that more substantive changes for the police budget could have seen wider support.

Councilwoman Barbara Sexton Smith, D-4th, for instance, said last week she would have been open to a smaller police budget, in theory, if it were aligned with what officers provide the community.

Timing played a role, she said, because there wasn't "robust discussion until very late."

"It carried with it a framework of being more reactionary than strategic thinking for a sustainable future," Sexton Smith said.

Councilwoman Nicole George, D-21st, a social worker, also expressed willingness to reevaluate police responsibilities and explore alternative response models. But she suggested there are "all kinds of questions" to be answered first.

Others, however, doubted whether such a proposal would've gotten support regardless of when it was pitched.

Many council members said they heard from constituents who wanted more police or who demanded they not cut funding. One described very different calls coming from constituents inside and outside the Watterson Expressway.

"We can take another look at what the role of officers are, and are there other programs that can help relieve some of their burden. I am open to those conversations. But there's no amount of mental health support that is going to solve the violent crime wave," Piagentini said.

LMPD's final budget is more than $190 million, though the general fund appropriation — the city's dollars, rather than state or federal grants — is slightly smaller than years prior.

Fischer recommended $178,850,500 from Louisville's budget, compared to a revised budget of $179,056,400 the prior year and an actual budget of $176,806,600 in fiscal year 2018-19.

(The uptick in the overall budget is partially attributable to a larger projected state grant amount and slightly more expected in agency receipts.)

Fact check: Louisville Police had a 'no-knock' warrant for Breonna Taylor’s apartment

What happens next?

Many Metro Council members say they hope to explore response models in the coming months.

Fox, the former police major, said "based on what our community is saying," something like a co-responder model should "absolutely" be explored.

Hollander, too, said he hoped for a "serious discussion" moving forward about co-responder and diversion models.

"What people want to know is, if you're taking away money from the police officers, what responsibilities are you also taking away? And who would fulfill those responsibilities?" Hollander, the budget chairman, said. "There wasn't time to figure that out."

Even Nichols, the FOP president, said the union is supportive of programs that could help to ease the responsibilities of LMPD, such as programs to help the homeless population or mental health treatment — though he stressed those dollars shouldn't come from an "understaffed, underpaid" police department.

For community advocates, the council is going to have to adapt or risk losing their seats.

"They should be aware that folks are not looking at them as the solution anymore. We're finding our own solutions," said Helm, the BLM organizer. "If they want to be more community-minded, they have to listen to the people in the streets right now."

West, too, said activists plan to "keep the pressure up."

"To me, it's embarrassing for Louisville not to make any significant changes regarding the police budget," the social worker said. "They have a lot of power, to be able to get the ball rolling on making really transformational changes in Louisville, instead of just things that work at the surface."

Follow Darcy Costello on Twitter: @dctello.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Breonna Taylor death: Why Louisville didn't defund its police