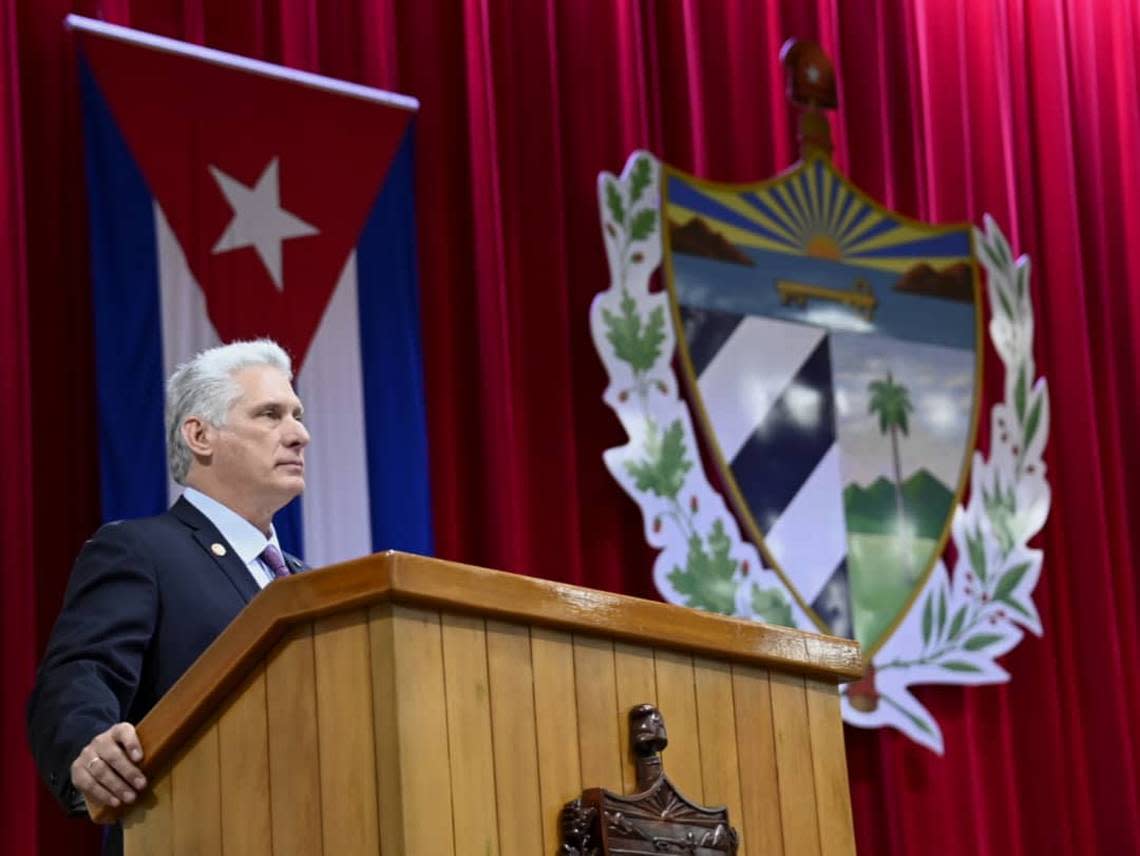

Despite his poor performance, Miguel Díaz-Canel gets a second term as president of Cuba

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Despite presiding over the worst economic crisis since the 1990s, one of the largest exoduses in Cuban history and a major crackdown on government critics, Miguel Díaz-Canel was appointed for a second term as Cuba’s president by the new members of the National Assembly controlled by the Communist Party.

He got 459 votes out of the 462 assembly members who voted. Eight of the 470 members were absent. For Díaz-Canel these next five years in office will be his last, as the recently approved constitution limits serving as president for only two terms.

Amid the economic turmoil and the unmet promises to improve the daily life of Cubans, assembly members voted to leave unchanged most of the country’s key positions.

Also reappointed Wednesday was the country’s vice president, Salvador Valdés Mesa; Prime Minister Manuel Marrero; the head of the National Assembly, Esteban Lazo, along with the assembly’s vice president and secretary. The three men are also on the 21-member Council of State, the executive arm of the National Assembly.

Even the derided ministers of economy, Alejandro Gil, and of public health, Jose Angel Portal Miranda, kept their posts. A veteran comandante of the 1950s Revolution, Ramiro Valdés, 90, will continue as one of a group of six first vice prime ministers.

Perhaps the biggest surprise Wednesday was the substitution of Rodrigo Malmierca, who was in charge of the ministry for foreign trade and investment. The role will be taken over by Ricardo Cabrisas, who will also continue serving as one of the first vice prime ministers. When Díaz-Canel announced the change, he said the country needed someone “with more experience and management capabilities.”

Much of the decision-making has been taken away from the Council of State and given to other government branches in recent years. The council is currently made of representatives of what are known as “mass organizations” under the Communist Party’s control, like the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution, the Federation of Cuban Women and the Young Communist League.

About half of the council’s seats were renewed with legislators that do not hold government positions or have a high public profile but ensure that diversity quotas are met.

All the candidates were selected by a commission controlled by the Communist Party or designated by Díaz-Canel as the newly elected president. And, as usual, the members of the National Assembly voted in favor of all the candidates proposed.

In a speech urging legislators and government officials to fight bureaucracy and inefficiencies, Díaz-Canel said the government should focus on food production, increasing foreign revenue and investment and fighting inflation. But he said officials could not produce a “miracle” because the U.S. embargo has “tied up our hands and feet.”

While Díaz-Canel devoted a long section of his speech to blasting the United States, accusing it of supporting an “uprising” that would end the revolution, some themes struck a different tone. He said the country should respect and welcome Cuban migrants who still “love their country” and want it to succeed, albeit he made sure to clarify that critics of communism who “have sold their soul to the devil” would not be welcome. And he praised the youth in Cuba, while acknowledging that they make up most of the people leaving the island.

There was also a sense of urgency in Lazo’s remarks after he was reappointed to lead the National Assembly.

“Our first task is the economy; that’s where we should direct all our efforts,” he said, adding that finding solutions to fight inflation and increased government oversight was also a priority.

Wednesday’s theatrics included members of the National Assembly praising the candidates, name-dropping Fidel and Raúl Castro, and voicing their support for the electoral process as an example of “true democracy.” Raúl Castro, who was presented as “the leader of the revolution,” despite not holding any official position beyond a seat in the assembly, was met with a long round of applause.

Díaz-Canel’s second term surprised no one, as there were no signs that Cuban authorities were considering a rival candidate, and Cuba’s electoral system shields the candidates favored by the Party from accountability on issues that are typically decisive in elections in democratic countries like performance, popularity or how the candidate’s party has handled important matters like the economy or foreign policy.

Central to the Communist Party’s tight control over the electoral process in Cuba is that the president is not elected by the direct vote of the majority of the country’s citizens. In fact, only a tiny percent of the population was able to directly vote for Díaz-Canel in a precinct in Santa Clara, when he was proposed as a member of the National Assembly, a prerequisite to holding his seat as president.

At the time of the vote Wednesday, he faced no competition. As Cuban journalist Reinaldo Escobar wrote for 14ymedio, a Cuban independent news outlet, “in Cuba, members of the assembly do not elect the President of the Republic; they vote for a single candidate.”

Allegations of irregularities and a relatively low turnout marked the vote last month to elect the assembly. Dissidents and activists urged Cubans not to participate, arguing that the process was not fair nor free, and that it only works to provide a veil of legitimacy to Cuban authorities. According to official numbers that cannot be independently verified, a third of the around 8.1 million registered voters stayed home and another 10 percent annulled their ballots or left them blank, all signs usually interpreted as a measure of discontent.

Díaz-Canel, who will turn 63 on Thursday, was handpicked by Raúl Castro as his successor, first as president in 2018 and later as the first secretary of the Communist Party, in April 2021. While the selection of a younger replacement who is not a member of the Castro family at first generated interest abroad regarding his potential role as a reformer, Díaz-Canel embraced the motto #somoscontinuidad — We are continuity — to clearly state he would not pursue that path.

Instead, he has overseen the issuing of a flurry of decrees and laws to further suppress freedom of expression and other civil liberties. And he went on live television to give a “combat order” to fellow revolutionaries to quash those who took to the streets on July 11, 2021, demanding freedom.

As a result, Cuba now stands as the country with the largest number of political prisoners, 1,006, in the region, according to the Madrid-based organization Prisoners Defenders.

But it is perhaps the chaotic economic and financial policies in the past five years that have made Díaz-Canel the target of people’s anger, which erupted during the unprecedented island-wide protests in 2021 as many chanted his name followed by an expletive.

Cuban state television on Wednesday framed Díaz-Canel’s first five years in office as particularly challenged by external factors beyond his control: a global pandemic and the Trump administration, which moved to tighten sanctions against the country’s military, restrict travel and remittances and include Cuba in the list of countries that sponsor terrorism.

But decisions made by Díaz-Canel’s government have made the situation worse.

Under Díaz-Canel, inflation soared after a flawed currency unification in 2021 when the country was being hit the hardest by the pandemic. His government decided to sell food in dollars, beyond the reach of many Cubans whose salaries are paid in local pesos, in the middle of widespread shortages. And at the time the health system was collapsing under the strain of the COVID-19 pandemic, Cuban authorities decided to invest significantly in producing local vaccines while the military continued funneling millions to build hotels.

Ultimately, although Díaz-Canel talked about the need to improve productivity and speed up reforms, he was unable to usher in a new era of economic growth.

As a result of such policies, the already low quality of life plummeted. Hospitals never recovered, and basic medicines and supplies needed for treatment are still not available on the island.

Díaz-Canel’s government has also been perceived as slow and inefficient in responding to several accidents, from the collapse of a hotel in Havana to a massive fire that ravaged a major oil storage facility in Matanzas.

More than 300,000 Cubans fled to the United States last year in a major rebuke of his rule.

There was little doubt from the beginning that Díaz-Canel’s power was going to be limited by the Party, the military and the old guard as he navigated a difficult transition from a government ruled by a Castro — Raúl Castro is 91 — to one still committed to communism but without a central, all-powerful leader.

Foreign diplomats, members of the business community, sources in the Catholic Church and activists have all shared with the Miami Herald their doubts about Diaz-Canel’s true role, as they see the all-powerful Ministry of Interior and the military gaining an oversize role in day-to-day decisions. In particular, Cuba observers are puzzled by the government’s reluctance to release the political prisoners, a major irritant in the relations with the United States and Europe, a position some said shows that Díaz-Canel lacks the political clout to convince hardliners of the benefits of doing so.

Relations with the United States remain a major issue for Díaz-Canel’s second term. While some official contacts have been restored with the Biden administration, in particular on migration, the prospects of better relations are bleak as the political prisoners and the island’s continuous support of Russia after its invasion of Ukraine stand in the way. In fact, Russia’s foreign minister, Serguei Lavrov, was expected to arrive Wednesday on the island, a stop in a tour to rally support among allies in the region.

In a rare display of candor, commentators on Cuban state television noted the enormous challenge Díaz-Canel and the new assembly face, not only in terms of the economic crisis but also politically, acknowledging that the country has become more “plural, increasingly similar to the world in terms of [political] conflicts,” said one journalist who even mentioned the July 11 protests in passing. They also highlighted the presence of representatives of private enterprises in the assembly. “It’s 2023,” one commentator said.

The migration crisis also crept in during the assembly session in an unexpected turn.

A member of the assembly mentioned Elián González — who as a boy was the center of an international child dispute between Miami and Havana, and who recently became a legislator —prompting a standing ovation for González, who was present in the Wednesday session.

But the assembly member who lauded González went on to say something else.

“One of my sons will be reaching the age of 18 in five years and will have to make decisions about his life,” said Edelso Perez Fleitas, the director of the National Union of Cuban Lawyers in the Ciego de Avila province. “You can count on me and all members of the assembly, and I am counting on you, fellow ministers and ministers, so that five years from now, when my son has to make that decision, we would have been able to build a country in which he wants to stay and continue sleeping in the same room he sleeps today.”