Despite racist barriers, Fort Worth’s early Chinese residents slowly built livelihoods

As Fort Worth industrialized, many citizens from other countries came to work and establish new lives. In 1908, there were workers from 30 countries represented at the meatpacking plants. None of them were Chinese.

This was due, in part, to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which said that immigrants had to be employed in mining in order to be allowed into the United States. The act dramatically reduced, but did not stop, Chinese people from coming to the United States.

Chinese immigrants were present in Fort Worth by at least the early 1870s — a note about the history of early Masonic Halls in Fort Worth says that the first hall, which was active in 1872, was located above an unnamed Chinese restaurant on Houston Street.

Most of the first Chinese who came to Fort Worth did so after the railroad arrived in 1876. These first immigrants typically ran or worked in laundries. Among them were Gee Hop and San Wah, men who operated two laundries listed in the 1878 city directory. By 1885, there were 17 Chinese laundries. Most of these early laundries were located on Main Street, and the staff usually lived on the second floor or in the back of the building.

Chinese laundry workers were in direct competition with Black workers, and there were organized efforts to force Chinese laundries to close. Those efforts were generally successful, as by 1905 there were only four Chinese-run laundry establishments in Fort Worth. The consolidation of smaller laundries into larger ones was also a factor.

In 1906, a reporter for the Fort Worth Record decided to make an evening visit to what he termed Fort Worth’s “little Chinatown” with a couple of police detectives in tow. Not surprisingly, many of the residents scattered upon his arrival. There weren’t enough Chinese residents – perhaps 60 – to fill the area east of Houston and west of Calhoun along 13th and 14th streets, but there were scattered lodging houses and businesses.

Along the way, the reporter described games being played (involving strips of red paper, Chinese coins and bone counters), a restaurant demonstrating the use of a “sun fong,” which was described as a Chinese counting board, and a large flat or apartment building which also contained the lodge room of the Chinese Free Masons. Today, this area comprises the southern end of the convention center and the northern edge of the Water Garden – part of the area known as Hell’s Half Acre.

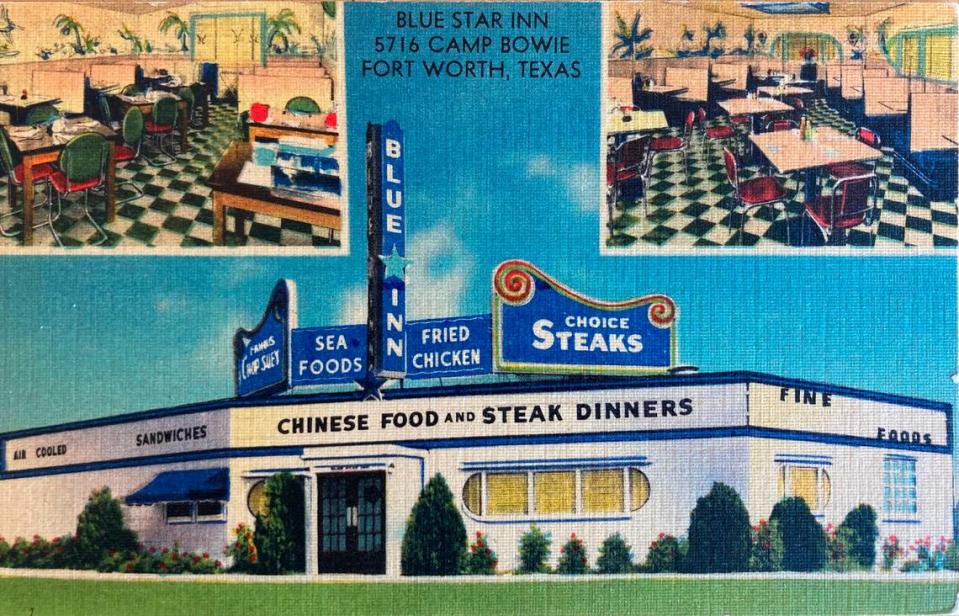

Chinese food became popular in Fort Worth in part because it was both tasty and inexpensive. Many restaurants were established at the turn of the 20th century. Among them are: English Kitchen Restaurant (Sing Lee, 1214 Main St., 1895), Chinese Restaurant (Hong On, 1409 Main St., 1903), Quong Chow Café (707 Main St., 1908-1913), and the Siebold Café (Eng Wing and Hong Tom, 804 Commerce St., 1918-1957).

The first Chinese restaurant in North Fort Worth was the Imperial Café, opened in 1909. Lew Y. Hoy purchased the Maverick Hotel and Café building at 100 and 102 Exchange Ave. for his enterprise. Although altered, the building still stands.

Chinese restaurant operators still faced prejudice. The first round of the battle came in 1903 when the Cooks & Waiters Union decided that its members would not work with Chinese restaurants in the city. By 1911, the struggle had shifted to one in which the waiters were opposed to “closed booths” in Chinese restaurants, which had doors hiding the diners from view.

After some study, it was decided that outlawing such “private” booths could also impact hotel and other private dining rooms. The waiters also countered that it was really the restaurant owners who were responsible for this campaign, and that the waiters wanted to be allowed to work in Chinese restaurants. The discussion dragged on through 1915, when the police chief finally took up the cause, declaring opposition to “booths that conceal parties.”

World War II relaxed the attitude towards Chinese, since the country was part of the Allied powers. The United States repealed the exclusion acts in 1943.

Although immigration quotas for Chinese were still low, many more began to come to America. Many, like Jow Ming “Jimmie” Dip, came shortly after the war ended and stayed to make their fortunes.

The Immigration Act of 1965 further opened the doors for people to come to the United States for study or immigration. It wasn’t always an easier journey than the pioneer Chinese immigrants faced, but the opportunities were there for those who wanted them.

Carol Roark is an archivist, historian, and author with a special interest in architectural and photographic history who has written several books on Fort Worth history.