Destruction of Indian burial remains at Bridgewater could complicate repatriation efforts

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

PART TWO — ‘A sunny pretty day’

Rebecca Jarrett was on a roll.

After years of starts and stops uncovering the fate of the burial mound of Indian Mound Road, she was cleaning her room and pulling books from shelves when her research literally fell into her lap. The four-page set of notes seemed flimsy next to all the time and thought she’d put into wondering about the former residents of this part of the Shenandoah Valley.

At work, a co-worker told her that she’d lived on Indian Mound Road for a few years and one of her children would stand by the window looking out on the road talking softly. When she asked her son what he was doing, he denied that he was talking to himself. He was talking, he told his mother, to the people who were coming out of the ground.

Rebecca took that as a sign to pick back up her research. She made a silent promise to those people coming out of the ground: if they helped her find the answers, she’d find a way to get the story out to people who lived here now so that the mound, and its people, would not be forgotten.

She reached out to NAGPRA about the Lewis Creek Mound in August 2022. She received a package of documents from the federal agency, detailing the bones, artifacts and nearly two dozen complete skeletons that had been found in the 1964 excavation just before the bulldozed. It appeared that all of those remains had gone, eventually, to the Smithsonian.

The News Leader reported that a replica of the mound would be built after the excavation. That never happened.

Digging further into the notes she saw that one complete skeleton — an infant — had been donated to Bridgewater College in 1964.

That feeling she’d carried with her for over a decade — there’s a story here — came back stronger than ever. Could there be a way to arrange for that Monacan child’s skeleton to get back to its people?

She wrote to Andrew Pearson, the Director of Forrer Learning Commons at Bridgewater College, asking him to confirm that the college still had the infant skeleton.

Pearson wrote back to Jarrett on Tuesday, Sep. 20, 2022: “Yes, Bridgewater College received a donation of an infant skeleton in October 1964 from the Southern Shenandoah Chapter of the Archaeological Society of Virginia. The skeleton was discovered from a bed of soil in a 1963 excavation of the Lewis Creek mound near Verona, Virginia conducted in advance of planned work by the State Highway Department on access roads and ramps to I-81. It was cremated in 1996. It’s currently registered with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). Let me know if you have any other questions.”

“Yes, I have a question,” Jarrett wrote back to Pearson. “Why the hell was it cremated?”

‘The way it was’

It was a “sunny, pretty day” on May 24, 1996 when Terry Barkley, curator for Bridgewater College library and archives, loaded a few plastic bins into his car’s trunk, climbed into the driver’s seat and headed north to Harrisonburg.

The drive up route 11 to the crematorium wouldn’t take more than 10-20 minutes. “It was right there on the main drag by JMU.” He’d called in advance and let them know what he needed.

When he arrived they sent him around to the back. The crematory operator was leaning against a car, eating a sandwich and smoking a cigarette. They unloaded the boxes from the trunk.

In the boxes were bones. Some nearly a thousand years old, from half a dozen sites in Virginia, Arkansas and Tennessee. One box contained the complete skeleton of the infant from the Lewis Creek Mound. Two dozen bones from a burial mound in Tennessee had been mixed in with the infant’s remains before the boxes were brought to Harrisonburg.

Barkley says it was not his decision to cremate the human remains. As the curator he reported to Ruth Greenawalt, the longtime director of the library at Bridgewater.

He doesn’t remember exactly who made the decision. “But I wouldn’t have gone to a funeral home in Harrisonburg on my own, you know, unless I was instructed to. So it was either the president or it was my boss, but it probably filtered down from the top.”

Barkley doesn’t remember whether he waited or went home then came back to pick up the boxes of ashes. But he did bring them back to the college.

Since retirement, Barkley’s written 8 books, mostly local histories. He wrote about an enslaved woman who was burnt at the stake in colonial Lexington and about the final stand of the University of Alabama’s corps of cadets in the Civil War, which concluded with the Union Army burning down a large portion of the campus.

Did it bother him as a curator trained at Harvard University that he was transporting human remains to be cremated? The cremation was carried out five years after NAGPRA required the protection and repatriation of those bones. Did he feel bad mixing the remains and destroying them?

“Well, I did, but if memory serves there was no other alternative,” Barkley said in a phone call on May 28, 2023 from Tuscaloosa.

“At the time, I don't recall anybody wanting the bones,” he said. "Anybody. And it's kind of the way it was. But we knew that we didn't need to have them on hand. And we figured, ‘Well, if we can't have them in this form, we'll cremate them, and then we'll keep the ashes so they'll still be on hand, they’ll just be in a different format, so to speak. So that's the way that was.”

Barkley says the Bridgewater remains were part of a large and strange collection of materials of dubious provenance that the college was not sure what to do with about the time that Barkley left his role in 2005 to go care for his ailing father in Alabama after his mother died.

“Andrew inherited this mess,” Barkley said, speaking Andrew Pearson, the director of Forrer Learning Commons at Bridgewater.

That mess was the Reuel B. Pritchett museum, which for many years occupied a space beneath the college’s auditorium in Cole Hall. The museum’s holdings were Pritchett’s personal collection, given to the museum by Pritchett himself, as well as additional gifts received over the years, including the Lewis Creek Mound infant skeleton.

“There were some real fine pieces in there that Reuel Pritchett had collected. Especially from churches of the Brethren and things like that. But then a lot of it was just like borderline junk. Yeah, it's like 50 pairs of salt and pepper shakers and crap like that.”

Barkley said the veracity of the sources of many of the items Pritchett himself brought to the museum was shaky at best. Some of those items were human remains Pritchett found on his own or that others had donated to him personally, and others like the Lewis Creek Mound infant skeleton were donated to Bridgewater in the decades following the Pritchett Museum’s establishment.

Barkley didn’t remember hearing anything about the Lewis Creek Mound specifically. But he did remember the infant skeleton. It was the only complete skeleton in the collection.

*

Bridgewater College cremated the remains of more than just the Lewis Creek Mound’s one-year-old Monacan skeleton, according to their own records submitted to NAGPRA in 2015.

They cremated human remains from sites in at least five counties in three states:

Human remains, including 23 unspecified bone fragments and associated funerary objects from an “unknown location” in Washington County, Tennessee, were cremated with the Lewis Creek Mound infant skeleton.

Human remains (11 human bones) and associated funerary objects from the “Jones Cave,” possibly the Jones Saltpeter Cave new Ewing, Virginia, in Lee County, were cremated. Before cremation, these remains were mixed with:

Human remains from an “unknown location” in Jefferson County, Tennessee, including 26 human bones, including fragments of skulls, pelvis, thigh bones and arm bones;

Human remains including at least two, and likely three, Native American human bones, including a fragment of a broken femur, from a spot near Fisher, Arkansas, in Poinsett County, Arkansas; and “possibly,”

A deer antler from a Native American grave in Cliff Cave (or Cloff Cave) in Cumberland County Tennessee.

***

A hand passes over the ashes you have become.

Words are spoken, some that may sound almost familiar, and voices that stir like water over river stones.

Have they found me? They are so close. Am I coming home?

Then they are gone.

***

Committed to compliance?

In January 2022 several members of the Monacan tribe visited Bridgewater and said prayers over the box of remains of the cremated infant.

Andrew Pearson would not respond directly to questions about the Lewis Creek remains. Abbie Parkhurst, the vice president of marketing and communications, would only confirm that the college is in the process of negotiating a claim by the Monacan people. “The Monacan Indian Nation has formally requested the repatriation of specific human remains and other culturally affiliated items within the College’s possession,” Parkhurst wrote in a May 17 email.

“Bridgewater College is committed to fully complying with NAGPRA regulations,” Parkhurst wrote.

But Bridgewater College has been out of compliance with NAGPRA since 1996, when they mixed remains from multiple burial sites, and then cremated those remains.

Melanie O’Brien, manager of the national NAGPRA program, was asked in a May 12 email if there is any legitimate reason for remains to be destroyed, cremated or otherwise materially changed.

“No. Again, if remains and artifacts are subject to NAGPRA, the only option is to repatriate under the Act,” she responded. “Any other action outside of NAGPRA is a failure to comply with the Act.

“A failure to comply with the Act is a civil violation. If the action that occurred … is a sale, use for profit, or transport for sale or profit, this may be a criminal violation.”

Seventeen months after the Monacans saw what was left of the infant skeleton taken from the Lewis Creek Mound, the box still sits in a vault beyond the archive room.

PART THREE — Whose bones are these?

“As I stood by the opened mound and looked on the large number of human bones thrown out with dirt excavated and others protruding out of sides of bank around the excavation, I asked myself, ‘Whose bones are these and from whence, and how came they here?’”

The Rev. David F. Glovier wrote this as part of an essay for The Staunton News Leader’s May 17, 1932 edition.

The chaos of what he saw was not the first time what has come to be called the Lewis Creek Mound had been disturbed.

There were also brief moments when the mound was protected.

Lewis Gibson, a man whose life straddled the turn of the 20th century, worked for decades on the farm where the mound was located. In 1857 Jacob Myers bought the farm. According to what Gibson told Glovier, “Mr. Myers sought in every way to protect and preserve this mound. One one occasion when some bones were discovered on top of the mound, he hauled dirt enough to cover them from sight. This was about the year 1870.”

Sometime around 1894 Gibson made his own discovery at the mound: about four feet above the base he found “a row of skulls laying side by side, and almost against each other, extending in a row running north and south.” Gibson told Glovier he thought they were the “skulls of Indians buried in a sitting position looking toward the West.”

Euley Glover was next to own and operate the farm. Though he only owned the farm for “two or three years” starting around 1906, he did more damage to it than centuries of erosion and flooding.

Glover repeatedly scraped the rich earth off the top of the mound to use for fertilizer. Lurtle Hawkins, whose father purchased the farm around 1910, was operating it in 1932 when two men, P.C. Manley and George Rusmissel, undertook to open the mound — with the Rev. Glovier witnessing the results of the dig. That foray into the mound in 1932 determined that Euley Glover’s fertilizing efforts had scraped three layers of burials off the crown of the mound.

Rusmissel’s credentials were described by the paper as being a man “very much interested in this type of work and (who) has done a considerable amount of it.” Manley’s qualifications to run a dig were not given at all. Manley promised that the “excavating was not done out of curiosity but from a scientific standpoint… and notes are being made, pictures taken, and drawings made of each discovery, so that a permanent record can be kept of the mound and its contents.”

“The entire collection from this mound will be kept intact, he added, and will eventually be displayed in Staunton,” according to the paper. No such display happened.

Another third of the way through the 20th century, as the final excavation of the Lewis Creek Mound was underway in 1964, The News Leader reported that all the artifacts from the Manley dig “previously uncovered were sold.”

For living Monacans in Virginia in 1932, things weren’t that much better. Like their ancestors, their identities were being slowly dug up and destroyed.

An administrator’s guide to wiping out a people

From a glass display case filled with examples of pipes, tools and pottery, Resilience and Pride gaze eternally toward the far wall of the middle room of the Monacan Museum on Bear Mountain.

Framed placards display the history of the Monacans as they adapted to the growing colonial presence on their continent: the ampersand-like signature of Shurenough, King of the Monacans, as it appeared on 1680’s Treaty of Middle Plantation; the establishment around 1800 of Oronoco, where they grew tobacco; and the purchase of a large plot of land on Bear Mountain where the tribe established a farming settlement, and where nearly a century later over 250 Monacans lived quietly. Many worked in local orchards; on a sunny day in April 2023 Lou Branham tells the story of how her great grandmother, high up a ladder in an apple tree, realized that her water had broken. She hurried down, returned to her home and gave birth to one of her fifteen children. Then once the baby had been fed and settled down with someone to watch it, she went back to the orchard to continue picking apples.

Monacan children were taught in a one-room schoolhouse on Bear Mountain.

In 1924, Virginia’s Director of Vital Statistics, Dr. Walter Plecker, tried to systematically erase the history of tribal people by lobbying the General Assembly to pass the Racial Integrity Act, which prohibited Virginia Indians from marrying whom they chose, and attempted to eliminate recognition of races as anything but “White” or “Black.”

Monacans chose to give birth to their children at home rather than have their tribal identity diminished further.

But in the record-keeping rooms of Virginia government, a “paper genocide” was already occurring, said Branham.

By the 1960s when the act was finally revoked and public schools were opened to Indians, the vital records of thousands of the Monacan people had been changed to wipe out their tribal heritage. This made it difficult for the tribe to find its own members and tell its history using public data when seeking state (and later, federal) recognition.

An exodus from the state had occurred throughout the middle of the 20th century because of Plecker’s efforts. Monacans left for more friendly locales such as Pennsylvania, New York, and Canada to the north, and Tennessee to the south.

Through it all, some Monacans remained, choosing to give birth at home so the hospitals would not have control of their birth certificates.

‘They walk in two worlds’

The quiet in the museum is broken by a woman coming in. “Are you Lou?” she asks. “I am!” Branham smiles. “It is so nice to finally meet you!” comes the reply, and in flow a group of a dozen visitors from the Lake Monticello area, about an hour away.

Folding chairs are placed in an oval around the room and Lou Branham sits with the group, Resilience and Pride over either shoulder, and talks about all things Monacan.

Like how family lineage is traced along the female line; how the Siouan-speaking people wandered Southeast across the country, following the bison, until they found a home around the Blue Ridge Mountains; how they moved from spear-wielding to bow-and-arrow hunters, and how cultivating corn gave them the stability to grow on both sides of the mountain range.

How when Monacan children finally were allowed into public schools in the 1960s, the school bus used to pass by them without picking them up. How Branham, who hosts supplemental Monacan history and culture classes for today’s Monacan teens, says of them, “They feel like they walk in two worlds.”

One retired teacher wonders if Branham's ancestors lived in longhouses and not teepees. Branham confirms it. Longhouses and wigwams, she says. She also tells the group that the valley Monacans did not have horses, even though most Hollywood depictions of Indians include the warriors on horseback.

If everything Hollywood said about Indians was true, she says to the visitors, “I should be riding buck-naked on a horse! But sure, I would love to have a teepee. A nice teepee by the river.”

Even as they prepare for their annual Pow-wow the first weekend in June, the Monacans wait to receive the final word that they will be getting back the remains of the infant taken from the Lewis Creek mound.

That the mound belonged to the Monacan people was well known even in the 1990s.

In 1988 The University of Virginia undertook fieldwork “under a court order issued for the scientific excavation and study of the human remains and requiring the reinterment of those remains with the Monacan Tribe of Virginia,” according to a paper in American Antiquity published in 2003 by Gary H. Dunham, Debra L. Gold and Jeffrey L. Hantman.

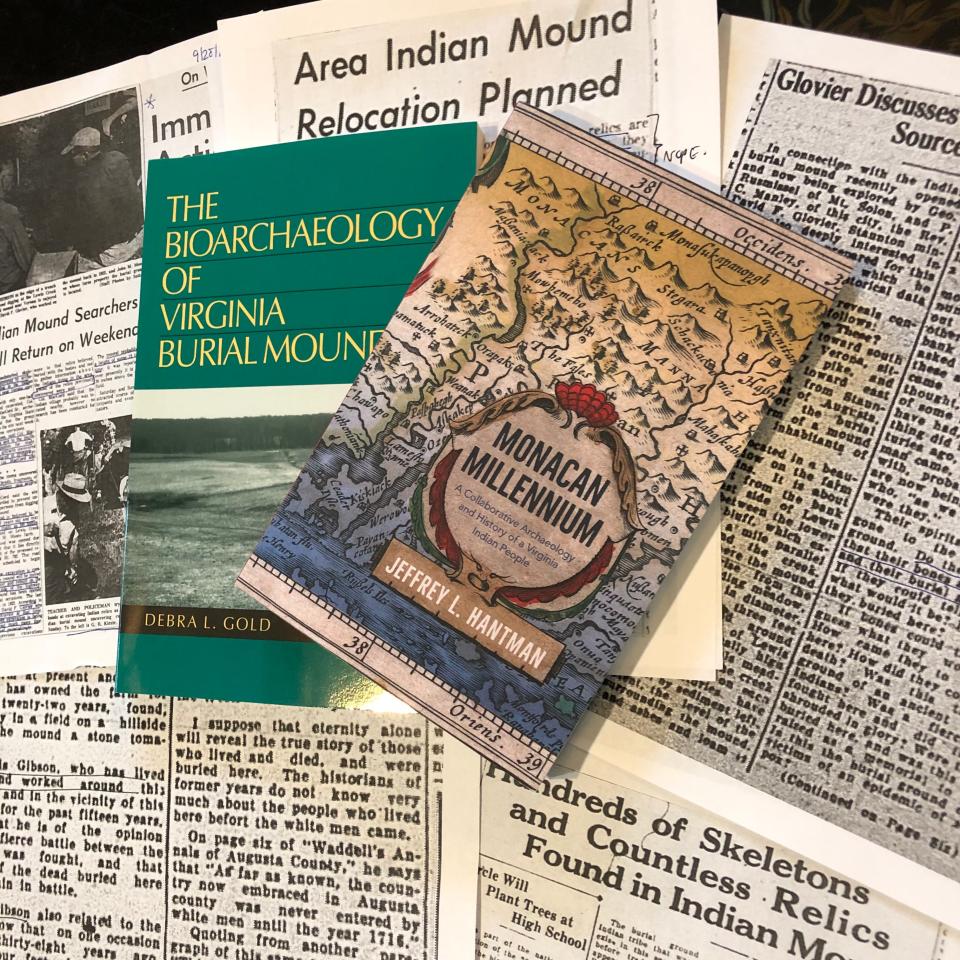

Gold’s book The Bioarchaeology of Virginia Burial Mounds (2004) is just one of several books and articles written about the Monacan people and their burial mounds in Virginia.

Nevertheless, Bridgewater College Executive Vice President Roy W. Ferguson, Jr. wrote in a 2015 letter to NAGPRA, “None of the remains or associated funerary objects in the College’s possession are culturally identifiable.”

Anyone with access to Google and a minute to spare, even in 2015, would disagree.

“It’s unfortunate to refer to the mounds by anything other than their association with the Monacan people,” University of Virginia Anthropology Professor Jeffrey L. Hantman said in an April 28 interview. “The Monacans today live largely in Amherst County, but their ancestral territory pretty much can be defined by these distinctive burial mounds.”

Hantman’s the author of the book Monacan Millennium (2018). In the early 1990s, when Bridgewater’s former curator said the college was unable to determine the owners of any of their human remains, Hantman had already worked alongside NAGPRA reviewers and the Monacan Indian Nation to salvage the Rapidan Mound, which was eroding into the river.

Hantman says the existence of the mounds also helps to dispel the idea that the Shenandoah Valley was somehow devoid of native settlements when the first Europeans began to explore the area.

“At least half of the Monocan mounds had burial populations of one thousand or more, which suggests a span of use of fifteen to twenty generations, or three to four centuries,” he writes in Monacan Millennium. The mounds were initially placed in the site of older villages, which shows an even deeper history of inhabitants in the valley.

Hantman was surprised to find out that Bridgewater had cremated the human remains of the Lewis Creek infant. “There is law protecting unmarked human remains, unmarked graves, and that law’s been on the books since the early 1990s.”

What will be done?

In the coming months the Monacan Indian Nation may finally get back the infant remains from the Lewis Creek Mound. Or it may not.

Bridgewater may face repercussions for the destruction of human remains. Or they may not.

If the Lewis Creek infant comes home, it won’t be to Verona and the site of the bulldozed mound. It will be to Bear Mountain and the Monacan land trust, where a reburial mound awaits it.

Lou Branham has indicated that if the child’s remains are repatriated, the Monacans may visit the original mound site for a ceremony after the child is reburied with its people.

Amateur historian Rebecca Jarrett plans to work on an application for a state highway marker on Indian Mound Road. The next round of applications are due August 1, 2023.

She's glad the story of the burial mound and the infant will reach people, and hopes to hear that the Monacans have finally recovered their ancestor. She wonders what the child’s mother would think if she knew in her grief that hundreds of years later people would be trying to do the right thing for her child.

There’s still a lot of unfinished business, she notes. Not the least of which, she thinks, is some acknowledgment from Bridgewater College that they did serious damage to multiple tribes over 25 years ago.

“An apology is the least that should happen,” she said.

“I could go into all the excuses people have for disturbing these sacred places,” Prof. Hantman said in April. “They wouldn’t have disturbed them if they were white cemeteries.”

*

There’s a photo in the Monacan museum of one-year-old Kenneth W. Branham.

In this small oval black and white picture of infant Kenneth, tucked into a family album like any photo of a one-year-old might be, like any photo of you or me as a child, the boy’s eyes are bright and full of life.

Performing a mental experiment not quite as impressive as the physical reconstruction of Resilience and Pride, looking at the photograph one can almost start to see the face of another one-year-old, the child who lived over 800 years ago in a place not far from where you live, whose remains still are so far away from being home.

At the Bridgewater College visitor’s parking area, a minute's walk from where that child's remains are locked up in a vault, a grass embankment leads to a concrete river bed. It guides a small runoff stream through campus to the widening North River. Near the lot, a pedestrian bridge leads visitors over the stream and onto the campus.

Where there's water, and people willing to guide a lost child, there's a way back home.

Read Part One here: 800 year old infant taken from a Verona burial mound may finally come home. With one inexplicable — and perhaps illegal — change.

Jeff Schwaner is the Virginia site editor, storytelling & watchdog coach for the Center for Community Journalism at Gannett. He can be reached at jschwaner@newsleader.com.

This article originally appeared on Staunton News Leader: Twists and turns on the road to bring an infant's remains home 800 years later