New details show interventions failed — again and again — to stop FedEx shooting

This story contains discussion of suicide. If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, call the Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255 or seek out area resources.

The afternoon just before Indianapolis' worst mass shooting was unusually calm in Sheila Hole's house.

She got off work at Five Guys on April 15 and came home with a burger, fries and a chocolate shake for her son. When she arrived, she found a rarity: Her suicidal and physically abusive 19-year-old was in a good mood.

After eating he told her he wanted a haircut. Their usual go-to, the Great Clips on Shadeland Avenue, was closed for remodeling. So they decided she would cut his hair there in their east-side home.

She messed up a couple of times so they talked about shaving his head. He was OK with that. One effect of his obsessive-compulsive disorder was that he didn't like having long hair.

The events of the past year weighed heavily on Sheila Hole. Domestic abuse, police interventions, his threats of suicide, his dead-end therapy sessions. The FBI task force officer who showed up at their door to say he was a neo-Nazi. The time he emerged from a gun store, smiling, with his new rifle.

Their relationship was always one comment or violent memory away from becoming volatile. But that evening, he decided to draw a hot bath for himself.

He sat it in for 30 minutes. She thought — she hoped — he was at peace.

She said goodnight and went to bed. He asked if he could order a movie. She told him he could.

Such moments — rare as they were — were why she never stopped trying, despite his violent tendencies, abusive behavior and consistently bad decisions.

"I think all is pretty good," Sheila wrote later in a journal documenting their final interaction.

He never ordered a movie. Instead, he slipped out of the house and traveled to a FedEx facility in southwest Indianapolis. He had two rifles in his car.

Once there, he selfishly and callously unleashed four minutes of terror.

He killed eight people and wounded five others before killing himself. Some of his victims were arriving or leaving work. Others were collecting their paychecks.

All innocent. All targets for no reason. All with grieving families left behind. Loved ones and a city searching for an answer. Why?

And could anyone have done something to prevent it?

FedEx shooting in Indianapolis: Who were the victims?

The reason for doing this story

Understanding the killer's backstory exposes not only his culpability — he is the one accountable for his actions — but also whether those with the power and responsibility to intervene did all they should.

IndyStar found law enforcement and mental health care professionals had multiple interactions with the killer. They were warned of his propensity for violence. But at crucial moments, their interventions failed.

The details of the killer's life were told to IndyStar by Sheila Hole in a series of interviews between September and November. She was hesitant to speak at first. She didn't want to cause the victims of her son's crimes any additional grief.

She said she decided to break her silence because she hopes telling the story will expose a series of shortcomings. That includes her own mistakes.

Sheila provided IndyStar with medical records and other documents dating back 10 years. She gave reporters a journal, which she kept in a briefcase by her kitchen table, that she filled after the shooting. It details her efforts to find help the year prior.

IndyStar also spoke with her close friend and her sister, who confirmed the killer's abusive behavior and the family's interactions with the FBI.

IndyStar has decided to share this story with a simple intention. We hope, much like Sheila Hole, that some good can come of this, whether by giving more attention to mental health care issues or holding accountable those whose job it is to protect us.

A history of mental illness

The killer had a long history of mental health issues.

That doesn't mean he was destined to become a mass shooter. One in five U.S. adults have a diagnosable mental disorder, according to the American Psychiatric Association.

"People with mental illnesses are no more likely to be violent than those without a mental health disorder," the American Psychiatric Association says. "In fact, those with mental illness are 10 times more likely to be the victims of violent crime."

Sheila began to notice issues with her son as early as fourth grade. His agitated behavior spurred her to bring him to Barrington Health Center on the southeast side of Indianapolis.

She took it seriously. She had reason to.

Seven years earlier, her son's father killed himself after an argument with Sheila over his drug use.

“I said, ‘You’re useless anyways, go kill yourself,'” Sheila told IndyStar. “I was angry. I said it. And he did it.”

A neighbor found his body in the family’s backyard. Their son was 3.

The experience shaped how Sheila would react years later, when her son threatened to follow in his father’s footsteps. “I couldn’t take it as a ploy,” she said.

When he began to exhibit symptoms of a mental health disorder, his mother felt confident she could find him help.

It was a belief borne of her experience with his older sister and only sibling. She had Tourette syndrome. To help her calm down, Sheila used to wrap her arms around her and squeeze tight. "I love you, I love you, I love you," Sheila would repeat.

The family’s physician was unfamiliar with Tourette syndrome, so he recommended an expert in childhood neurology. She called the office, but getting an appointment proved difficult.

So she began dialing numbers that differed from the main line by just one digit. Finally she landed on the direct line to the expert's office. A staff member booked the appointment.

The appointment led to her daughter's diagnosis of Tourette syndrome, and medication that helped her manage the neurological disorder.

Now, she focused that same determination on her son's behavior.

"I was like, all I’ve got to do is... get in and tell people what’s going on,” she said.

Troubling behavior

At Barrington Health Center, he was diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder and prescribed Lexapro, a depression and anxiety medication.

The following year, as he started fifth grade, the problems grew. During a 2-month period in the fall of 2012, medical records show he resisted going to school. He was aggressive with his mother “to the point that mom doesn’t know what to do anymore.” His mother told his therapist "he has always been aggressive to her but she never told anybody.”

Twice in the medical records there were references to police being called to the family's home.

His behavior had deteriorated. The records described “aggression to others, blatant disrespect for authority, property destruction." He "often loses temper, argues with adults, defiance, often blames others for his/her mistakes, is often touchy or easily annoyed by others, is angry and resentful.”

Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms were also noted. He “has had a lot of stress and trauma — dad killed himself, several deaths in family.”

For the first time, self-harm was listed as a risk factor.

He was further diagnosed with disruptive behavior disorder and anxiety disorder. Several behavioral therapy sessions followed. He was prescribed a stronger dose of Lexapro, plus Intuniv, an attention deficit hyperactivity disorder medication.

Still, none of it seemed to make a significant difference, Sheila said.

Water fight turns violent

On May 16, 2013, her son, then 11 years old, was arrested after a water fight with his mother’s boyfriend turned violent. The boy was upset he had been sprayed with a hose. He began yelling and spraying the inside of the house, according to a police report.

After the boyfriend left, the boy locked himself in the bathroom and began destroying it. When his mother picked the lock, he charged at her, she told police. He punched and slapped her in the face, kicked her legs, bit her, and then, according to the police report, stabbed her in the arm with a table knife.

He was transported to juvenile detention for a few hours and later put on probation for several months, his mother said.

That fall, he began attending Raymond Park Intermediate and Middle School. It didn't go well. His inflexibility caused frequent outbursts. He was often overcome with anxiety. After just a few weeks, he dropped out.

"I'm fighting for like two hours to get him to school. We go in there, he's crying, I'm crying," Sheila told IndyStar. "And they're like, 'He can go home.' After 12 or 13 times I'm like, OK, that is not doing us any good."

Staying home reduced the stress in his life. In that sense, Sheila said, the isolation was something of a relief. But it did little to improve his underlying mental health challenges. He remained depressed, she said.

He enjoyed spending time on his computer and playing video games. But he never attended high school and did not graduate. He also refused counseling, Sheila said.

Over time, he developed a fascination with the military.

He began going to the nearby Indy Gun Bunker, a firearms and military surplus store. He would buy MREs — meals ready to eat — and try on camouflage jackets.

He even thought he might enlist. He and his mother spoke with a recruiter after he turned 18. But they were told his braces would prevent him from serving, Sheila said.

Then, on March 2, 2020, he bought something else from the surplus store.

‘He’s going to kill himself’

He had threatened suicide before. So when he told his mother he wanted to purchase a gun, he didn’t hide why.

“He says he's going to get a gun and kill himself,” Sheila told IndyStar.

She refused to drive him to the store at first. When he said he would drive himself, she relented and went with him. She was worried, but told herself, he probably doesn’t have enough money to buy a gun.

She also believed there would be a several-day waiting period before he could take possession of the gun. She was wrong.

“I couldn’t even believe he was filling out the paperwork,” she said. She considered screaming in the middle of the store: “He’s going to kill himself!”

Then something happened that bought her time. He successfully purchased a shotgun, but the store was out of ammunition.

When they got home, she tried to talk to him. “If you won’t go to counseling, I have to call someone on you to stop you from doing this,” she remembers telling him.

He got angry. He punched her.

“It’s my life, I’ll end it the way I want,” he told her. “If you call the police I will point an unloaded gun at them and they will shoot me anyways.”

Driven by desperation, Sheila and her daughter made a plan that night. The next day, they would go to IMPD’s East District office. They'd plead for help.

Officers were in the middle of roll call when the two women arrived. Sheila banged on the door until someone opened it.

Police reports from that day show she told officers everything: Her son had purchased a .410 caliber shotgun the day before. He had threatened suicide by cop. He had hit her. His father had killed himself.

She said she also told them he'd been diagnosed with several mental health disorders.

When police arrived at the home, Sheila called her son downstairs. Police handcuffed him. He “became immediately anxious,” a police report says.

“Please just turn the power strip off on my computer,” he told officers. “I don’t want anyone to see what’s on it.”

Police confiscated the shotgun under Indiana’s red flag law, which allows law enforcement to seize firearms without a warrant when they believe someone is a danger to themselves or others.

‘He should have been red flagged’: Mother of FedEx shooter speaks out in Fox59 interview

They also saw what they described in the police report as white supremacist websites on his computer. Sheila said one of the officers told her that her son was on a neo-Nazi website, talking to someone in Germany with neo-Nazi rhetoric.

Sheila said she told the officers to take his computer and arrest him, but they didn't.

Instead, they kept him on the couch for about 45 minutes.

He downplayed any suicidal thoughts or plans. But he voiced feelings of sadness and depression, according to the police report. He said he would benefit from counseling. So he was transported to Eskenazi Hospital for further assessment.

Guns were now out of the picture, Sheila thought. Her son was finally going to get the help he needed.

Neither of those things turned out to be true.

‘They brushed him off’

He spent less than two hours at Eskenazi before he was released, Sheila told IndyStar.

Medical records show he was seen by an emergency medicine physician. The records show the physician was aware that he was brought in by police, had recently purchased a gun, made statements that he did not want to live and contemplated pointing a gun at police in an attempt to end his life.

“The patient denies this in its entirety to me,” the physician wrote, “says he feels fine has no medical complaints and (does) not feel like he would hurt himself or anyone else.”

There is no indication in the medical records that he was seen by a psychologist or psychiatrist.

Under “Final diagnosis,” the physician wrote, “None.”

The physician did not respond to inquiries from IndyStar, including a note left at an address associated with him in public records. Reporters sent questions to Eskenazi about whether a formal psychological assessment or suicide risk evaluation were performed. Todd Harper, a spokesman for Eskenazi, said the hospital could not answer specific questions because of patient privacy requirements.

“We are deeply saddened by the tragedy at FedEx,” Harper said in an emailed statement. “Eskenazi Health follows standard evidence-based policies and practices governing the assessment of safety and suicide risk in all patient care settings. Decisions regarding involuntary detentions and treatment are made based upon clinical review and clear legal parameters in place to protect individual rights.”

Mental health experts who reviewed the medical records at IndyStar’s request said hospitals should be equipped to deal with complex psychiatric issues, especially when someone presents a threat to themselves or others. The reality is, they often are not.

“That’s not uncommon, but they brushed him off,” said Jeffrey A. Lieberman, chairman of the Department of Psychiatry at Columbia University and a former president of the American Psychiatric Association. “They sent him out because he said the right things initially and they didn't see any extreme acuity of the situation.”

‘They cut him loose’

The decisions made at Eskenazi would also play a role in determining his access to firearms.

On March 3, 2020 — the day police responded to the home and confiscated his shotgun — it should have set in motion the filing of a probable cause affidavit with a Marion County judge. Under the red flag law, police must file an affidavit with a judge within 48 hours of confiscating a weapon.

But at that time, police were first sending the probable cause information to be vetted by the Marion County Prosecutor’s Office.

Had prosecutors decided to bring the case before a judge, a hearing would have been set within 14 days. If the judge found the then-18 year old to be a danger to himself or others, he would have been prohibited from possessing or purchasing firearms — including the rifles he would later use to carry out the FedEx shooting.

But Marion County prosecutors declined to open a red flag case.

Marion County Prosecutor Ryan Mears would later blame what he called shortcomings in the law. He would also stress the quick release from the hospital.

“He was cut loose,” Mears said during a press conference in April defending his office’s decision.

“They didn't so much as prescribe him any additional medication after he walked out of there or any medication. And so we're left with a situation (where) we have one incident, he was treated by mental health professionals, they didn't civilly commit him, they didn't prescribe him any additional medication, and he was cut loose.”

‘They could have arrested me’

Sheila received a call to pick up her son from Eskenazi less than two hours after he had been detained. She was shocked — and afraid.

“I figure he’s going to beat on me for doing this to him,” she told IndyStar.

For a while, he said little about what had happened. Sheila asked if they talked to him or helped him. "No," he said. He did, however, express concern he had been labeled a neo-Nazi.

A day or two later, his mom was sitting on a chair in the living room, playing Candy Crush on her phone. Suddenly, he emerged from his bedroom and sprinted down the stairs.

He ran up to her, she said, and smacked her on the side of the head as hard as he could.

She felt her eye shake in its socket. Her phone went flying across the room.

“What did I do?” she asked.

He said he understood why she called the police about the gun. But “you did not have to tell them that I hit you," he said. "They could have arrested me for domestic violence!”

I wish they would have, Sheila thought.

IMPD tries to return the gun

That week, Sheila received a phone call from a woman at IMPD. She was trying to reach her son about the gun, but he was not answering. Sheila told the woman she would tell him to call her.

The woman called again an hour later. She said the woman told her that her son had an attitude problem, and that he hung up on her. The woman said she just needed to know if he wanted the gun back.

Sheila couldn’t believe it. “Hell no!” she remembers telling the woman.

The woman told Sheila she needed to hear it from him. So Sheila convinced him to get on the phone and tell the woman IMPD could keep the gun.

Sheila didn’t fully understand the ramifications of the phone call at the time. She didn’t know then that the prosecutor’s office would not be filing a red flag case.

But she did know this: She was exasperated. The experience with Eskenazi and law enforcement had left her disillusioned.

“When a person is suicidal and chooses to use a weapon of a gun as their means to attempt that, and then ultimately you’re just handing it back to them?” she told IndyStar. “Now, what kind of message does that send to the suicidal person?”

Officers from IMPD’s behavioral health unit stopped by to check in a few days later. Sheila asked them to leave.

What was on his computer?

Police intervention prompted little action from doctors or prosecutors, but it did draw the attention of another agency — the FBI.

The material IMPD saw on his computer led to a referral to the FBI. Details of what exactly police saw have never been made public.

Sheila said she went into her son's bedroom after police left on March 3, 2020. On his computer screen, she said, was a Google search for a song about Krieg, an apocalyptic, nuclear-decimated world from the fantasy game Warhammer 40,000. Inhabitants of the world, known as the Death Korps of Krieg, are fatalistic soldiers whose appearance and insignia are largely based on the German militaries of WWI and WWII.

The songs in the search results were dark and, in hindsight, disturbingly prescient.

The top result was a song that referred to “a suicide mission” and included lines such as, “Here, corpses are winners...our deaths have been assigned — and I choose mine...through our pile of corpses, triumph we shall gain.”

Another top search result featured an image of an iron cross and a song that began, “I’ve got the reach and the teeth of a killin’ machine.” Other lyrics include, “I’ll bring death to the place you’re about to be: another river of blood runnin’ under my feet."

It's unclear if that's what police saw. But whatever they saw led to a referral to the FBI’s joint terrorism task force.

‘No, no, no,’ she screamed

Later that month, Sheila said she received a phone call from FBI task force officer Matt Stevenson. He needed to talk to her. They agreed to meet at the Propylaeum, where she worked at the time. The interview took place in his car, Sheila said.

He asked her about what police saw on her son’s computer. She showed him the Krieg song search page. Then Sheila said he asked her a series of questions.

Is he a loner?

Yes, she said.

Does he have a girlfriend?

No, she said.

Does he get on 4chan, an anonymous internet forum?

Yes, she said.

Does he talk to people online?

No, she said, but he does get on Omegle, a website that randomly pairs strangers in anonymous one-on-one chats.

After answering all his questions, Sheila said Stevenson said something that burned in her brain.

He said her son hit every red flag for a mass shooter.

“No, no, no," Sheila screamed.

She said she told Stevenson to go take his computer and arrest him. Stevenson told her he needed to talk to him first, she said.

Her friend and co-worker, Janice Radford, told IndyStar she saw Sheila get out of Stevenson’s car. Sheila told her what Stevenson said.

“She was extremely upset,” Radford said. “She was crying. She was shaking. I had never seen her that upset before.”

Another FBI interview

A few weeks later, in mid-April of 2020, Sheila said Stevenson and another member of the task force showed up at her home one morning.

The interaction that followed — as relayed by Sheila Hole — raises questions about whether the FBI's involvement accomplished anything other than unwittingly antagonizing a person its task force officer had already described as exhibiting characteristics of a mass shooter.

She doesn’t remember the entire conversation. IndyStar sent the FBI a list of questions about the exchange, but the bureau would not comment. Here's what Sheila Hole told IndyStar she does remember.

Stevenson asked her son why he bought the shotgun. He told him he bought it to kill himself.

Stevenson then asked about his internet activities. He acknowledged using 4chan. He told Stevenson it wasn’t all bad, some things were funny.

Then Stevenson asked a question that, to Sheila, seemed to come out of nowhere.

Did he like My Little Pony?

He said he did.

His mom was startled. She was unaware of so-called Bronies: adult fans of the animated children’s series. Many members of the subculture genuinely enjoy watching the show with its bright colors and positive messages. But since the subculture’s inception on 4chan, there have always been strains of sexualization and racism.

Sheila said Stevenson went on to say My Little Pony message sites were a way for neo-Nazis to talk to each other and make plans. He asked her son if he had talked to anyone on those sites. He insisted he hadn’t. He told Stevenson he could take his computer, Sheila said.

It was the third time Sheila or her son had offered the computer to law enforcement. And for the third time, they declined, she said.

Stevenson then asked him what he was going to do with his life. The teen suggested he could work for the FBI, help them out.

Sheila said Stevenson shot him down. You need to get your mental health together, she remembers Stevenson saying.

As they left, Sheila heard Stevenson say something over his shoulder: Don’t hit your mom. She had nothing to do with this.

As soon as they were gone, her son became agitated, furious.

“Why didn’t you say something,” he screamed. “How come you let him talk to me like that?”

‘They don’t have a flag on me’

The run-in with police and the FBI became an obsession. How dare they? he felt. Their questions humiliated him. Especially the accusation that he was a neo-Nazi.

“Let’s just try to go one day not talking or thinking about it,” Sheila told him.

That summer, he told her he wanted to move out of their home. Sheila thought it might be good for him. Living on his own might help with his obsessive tendencies and his anger.

They put a down payment on a trailer on the west side, close to his aunt.

Now that he was on his own, he needed protection, he later told his mom.

He was going to a gun store.

On July 7, 2020, she went with him to Indy Arms Company on East 55th Street. She told IndyStar she went because she didn’t believe they’d sell him a firearm. After what happened in March, she was sure he’d been “red flagged.”

If he comes out furious, she thought, I don’t want him driving. If he comes out furious, she thought, he’ll probably beat me.

Sheila didn’t go in with him. She chain-smoked Marlboro Lights outside in the car. Ten cigarettes — and less than 20 minutes — after he walked in, he walked out with an HM Defense rifle.

"My emotions were off the charts," she said.

He was smiling.

“They don’t have a flag on me,” he told his mom.

For a second, she was relieved. The fact that he could buy a gun suggested the FBI didn’t act on what Stevenson told her. Maybe federal law enforcement didn’t really think her son was a mass shooter. And seeing him happy was like coming across an oasis after years of wandering.

Then reality set in. Her suicidal son had a firearm again.

‘I don’t see any white supremacists doing anything’

On Aug. 19, 2020, one day before his 19th birthday, he would have one last known interaction with law enforcement.

That day, Sheila was driving her son home from the dentist when she looked over and saw he had Stevenson's business card in his hands. He was dialing his number.

She reached over and tried to stop him. He pushed her hand away and called Stevenson multiple times. Sheila told IndyStar that when they finally connected, her son went on a rant.

“How can you bring your personal opinion into an investigation?” he asked Stevenson. “What side should I join if you gonna label me?”

Then Sheila said her son shifted the conversation to race.

“You’re labeling me a neo-Nazi white supremacist but you got the FBI kneeling to Black Lives Matter,” he said. “And I don’t see any white supremacists doing anything. But Black Lives Matter are out here burning, rioting.”

He's losing his shit, Sheila thought.

She figured the unhinged call would place him back on the FBI's radar. But as far as she knows, that phone call ended the FBI's involvement with her son.

When IndyStar reached out to the FBI after he shot and killed eight people, the bureau would only say it had previously concluded he had displayed no Racially Motivated Violent Extremism ideology.

The next day, Sheila and her son did nothing. He didn’t feel like celebrating what would be his final birthday.

New job at FedEx

That August, he started a new job at the FedEx ground facility near the Indianapolis International Airport. He liked it there.

SUBSCRIBE: Help support quality journalism like this.

Sheila spoke with him over the phone almost every morning "to keep him calm, help him see things can and will get better,” she said. He "seems good," she wrote in her journal.

But there was one thing he didn't tell her. In September 2020 he purchased a second rifle — a Ruger AR-556. Sheila said she later learned he purchased it at the Indy Trading Post on Madison Avenue.

About that same time, he told her he hadn't shown up to work for a few days. He assumed he was fired. He couldn’t get out of bed, he said. It was probably his depression, Sheila told IndyStar.

But then he went to FedEx to pick up his last paycheck and found out he wasn’t fired after all. He returned to work.

By October, he had stopped showing up to work for good.

‘No guns in the house’

He started having second thoughts about living on his own. He wanted to move back, he told his mom in February 2021.

She said he could. But he had to go to counseling.

He agreed. On March 19, they went to an Eskenazi Health clinic. Sheila sat in the waiting room. Her son sat in the car outside, rocking back and forth. He was “highly agitated,” Sheila said.

Hours passed. His name was never called.

Sheila approached a staff member. “I’m willing to sit here until you guys close,” she said. “He needs to be seen.”

It doesn’t look like they’re going to get to him today, staff told Sheila.

She started to cry.

Four hours passed. They never saw a mental health professional. But before they left they received good news. He was put on the schedule for the following Monday.

That morning, he met with a social worker at Eskenazi Health’s clinic on Crawfordsville Road. It was the first time he’d seen a counselor in almost a decade.

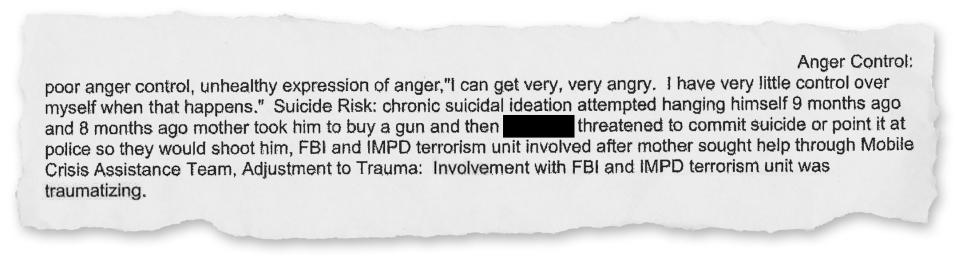

The five pages of notes from that session are thoroughly detailed. He had generalized anxiety disorder, panic attacks, recurrent major depressive disorder and chronic suicidal ideation, the notes say. He had obsessive-compulsive tendencies, poor anger control and impaired social functioning.

“Involvement with FBI and IMPD terrorism unit was traumatizing,” the notes say. Around the time of that incident he tried to hang himself, he told the counselor.

He also told the social worker he excessively worried “about everything, financial problems, my mental state.”

“I worry that I could kill myself one day.”

Medication for psychiatric symptoms would be good for him, the notes say. But he was never given medication, according to Sheila. And his records never indicate he received a prescription.

He was deemed a “moderate risk” and given a suicide prevention safety plan.

One of the plan's steps: “No guns in the house.”

‘Doesn’t care about the lives of others’

Nine days later, on March 31, he met with a different Eskenazi Health social worker.

He told the social worker "he doesn’t have empathy; he doesn’t care about the lives of others even his own mother,” the Eskenazi therapy notes say.

His run-ins with IMPD and the FBI the previous year came up again. He said he was intimidated. They were too intrusive. The experiences "made him very angry towards society and law enforcement," the notes say.

His most recent suicide attempt also came up in greater detail. He tried to hang himself but failed. He didn’t have the rope positioned correctly.

He took a suicide risk assessment test with the social worker. “Risk was not identified,” according to the therapy notes.

‘You’re not going to like this’

He met with the social worker again on April 14, 2021 — the day before the shooting.

The last counseling session of his life focused on “strategies to address anger issues,” according to the social worker's therapy notes.

He told her he might be bipolar. He said he might be a "vulnerable narcissist."

He also asked if his mom could then join them. Sheila told the social worker about March 3, 2020, when IMPD came to their home after Sheila reported her son to authorities, the therapy notes say.

Sheila said she didn't realize he'd "be able to own a gun so soon," according to the notes.

She talked about his obsessive-compulsive disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and how they affected him in elementary school.

The social worker also noted that one of the triggers that remains is that no one is allowed to touch his Applejack plush toy. He "said he loves ‘My Little Pony,’” the notes say.

Although not reflected in the notes, Sheila told IndyStar he brought up white supremacism.

“You’re not gonna like this,” he told the social worker, who is Black. “They labeled me a white supremacist.”

When the social worker didn’t react, he continued.

“You’re not gonna like this either,” he said. “I’m not a white supremacist, but if I was, that would be my legal right to be one.”

Sheila said her son gave a warning, also not reflected in the notes: "I have no empathy for anyone. I’m a danger to society. Society should be afraid of me."

Sheila started crying. She said she told the social worker, "He needs help."

The social worker patted her on the shoulder, Sheila said, and said, "We'll get him. He'll be fine."

The social worker did not respond to inquiries from IndyStar, including a note left at an address associated with her in public records. A spokesperson for Eskenazi also declined to answer specific questions about the counseling sessions, citing patient privacy requirements.

The FedEx shooting

The following night, after his haircut and bath, he made his final post on Facebook. His account was later taken down at the request of Indianapolis police, but the post was referenced in an internal Facebook memo reviewed by the Wall Street Journal.

It featured the image of a cartoon pony and was timestamped 10:19 p.m.

“I hope that I can be with Applejack in the afterlife, my life has no meaning without her,” the post said. “If there’s no afterlife and she isn’t real then my life never mattered anyway.”

Less than an hour later, he pulled into the parking lot of his former employer. Police said he likely chose FedEx simply because he was familiar with it.

The massive facility near the Indianapolis International Airport was bustling with activity.

He went into the building and spoke with security, then returned to his car. He retrieved the two rifles he had purchased and began to spray gunfire. He killed four people outside. Four more inside the building. Five others were injured.

The massacre lasted about four minutes. Then he killed himself.

‘An act of suicidal murder’

After the shooting, the FBI reappeared. This time, they were tasked with trying to figure out why it had happened.

Along with Indianapolis police and the U.S. attorney's office, the bureau conducted more than 120 interviews, issued more than 20 search warrants and subpoenas and reviewed more than 150 pieces of evidence.

They also pored over his computer and other devices.

They discovered about 200 files with German military and Nazi content. However, they noted, that was “an extremely small percentage” of the roughly 175,000 files they reviewed.

Despite that content, the agency announced in July that the killer's motivation did not appear to be based on bias or the desire to advance any ideology. That had been a major concern of the Sikh community, who lost four of its members in the shooting.

Instead, the FBI called his actions “an act of suicidal murder” intended to “demonstrate his masculinity and capability while fulfilling a final desire to experience killing people.”

Experts weigh in

It will never be known for sure if a more successful law enforcement or mental health intervention may have prevented the shooting.

That said, mental health experts asked by IndyStar to review the medical records and therapy notes had harsh criticism.

"There was a tremendous failure to address the complexity and gravity of his mental disorder," said Lieberman, chairman of the Department of Psychiatry at Columbia University and a former president of the American Psychiatric Association.

The diagnostic evaluations were "inadequate," Lieberman continued. The treatment he received focused on symptoms, not underlying issues. Those could have been uncovered through a deeper neuro-psychological assessment and questions about his developmental history, he said.

He compared the treatment to someone who is given aspirin to quell a fever, or cough medicine to treat a cough, even though the cause of those symptoms is pneumonia or a strep infection.

If he indeed said he was a danger to society and that society should be afraid of him, it should have "set off all kinds of alarms," Lieberman said.

"You immediately act to restrain, admit or take them under observation." They should also be reported to law enforcement, he said. And if you think the statement is vague, you need to ask more specific questions to determine if the person is a danger, he added.

Christine Sarteschi, a professor of social work and criminology who has written extensively about mass murder, said the discrepancy between the medical records and Sheila's account of what he said during his final counseling session is "worrisome."

Miscommunications do happen. But if such a statement was made, Sarteschi said, it should have been included in the notes.

She was also surprised he was never deemed more than at moderate risk for suicide when social workers saw him in the spring. "He did seem like a high risk to me," she said. "For sure."

"To me, it's a system failure," she said. "And until we, as a society realize that we can't continue to operate and have a mental health system that has so many gaps in it, and holes in it, I worry that this kind of thing will continue."

‘I grieve those people’

On a recent Tuesday afternoon, Sheila's eyes followed a delivery vehicle as it passed in front of her porch and down the street.

"Every time I turn around there’s the FedEx truck."

She can be found here most days. Sitting outside on the porch.

Waiting. Though she’s not sure for what.

For lawyers representing the victims’ families to pull up, step across her driveway and tell her it’s time for her to talk.

For a victim’s family member to pull up and shoot her.

She wouldn't blame them if they did. Whatever the families want.

During her trips in public she carries copies of a police report that she hands out to people who approach her. It's the report that details law enforcement's concern he was a danger to himself and others.

So much so that they took his shotgun that day. So much so that they took him to the hospital.

It's how she tells people he was within the grasp of those who might have prevented the city's deadliest mass shooting.

She wants people to understand that she tried.

And she wants her son to know that when she cries these days, it’s not for him. It's for the victims.

“I grieve those people," she would tell her son if she had the chance, "more than I ever will you.”

Contact IndyStar reporter Tony Cook at 317-444-6081 or tony.cook@indystar.com. Follow him on Twitter: @IndyStarTony.

Call IndyStar courts reporter Johnny Magdaleno at 317-273-3188 or email him at jmagdaleno@gannett.com. Follow him on Twitter @IndyStarJohnny

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: FedEx shooting: How inadequate interventions failed to stop killings