Detroit promised to end water shut-offs for low-income residents. Advocates say we’re not there yet.

Low-income Detroiters were promised a plan to put an end to water service shut-offs “once and for all.”

In six months, a temporary ban on the controversial practice runs out, and residents with past-due bills — including one low-income Detroiter who owes more than $5,700 — will once again be at risk of losing access to water.

City officials said they will prevent service denials for low-income customers who enroll in payment assistance programs, but admit that funding to support the programs isn’t guaranteed to continue.

Meanwhile, state lawmakers representing the city and some of its fiercest water rights advocates say they’ve largely been left in the dark about Detroit’s plans to permanently cease shut-offs and restructure water rates.

“There’s been no meaningful engagement. It’s been very secretive,” said Nick Leonard, executive director of the Great Lakes Environmental Law Center. “That’s bad practice.”

More: Water is unaffordable across Michigan, study shows

More: Detroit water shut-off protections extended through 2022, permanent stop planned

The Wayne Metropolitan Community Action Agency, a nonprofit that administers one of the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department assistance funds, has met in recent weeks with a couple water rights groups to brief them on the city’s plan.

DWSD Director Gary Brown is expected to introduce his rate change proposal Wednesday to the Detroit Board of Water Commissioners. He told BridgeDetroit and the Free Press in a recent interview that the plan is modeled after the “lifeline rate” system adopted by Washington, D.C., in 2017.

The water department also expects to expand its Water Residential Assistance Program, or WRAP, which offers a monthly credit to low-income Detroiters. Right now, there are 2,300 households enrolled.

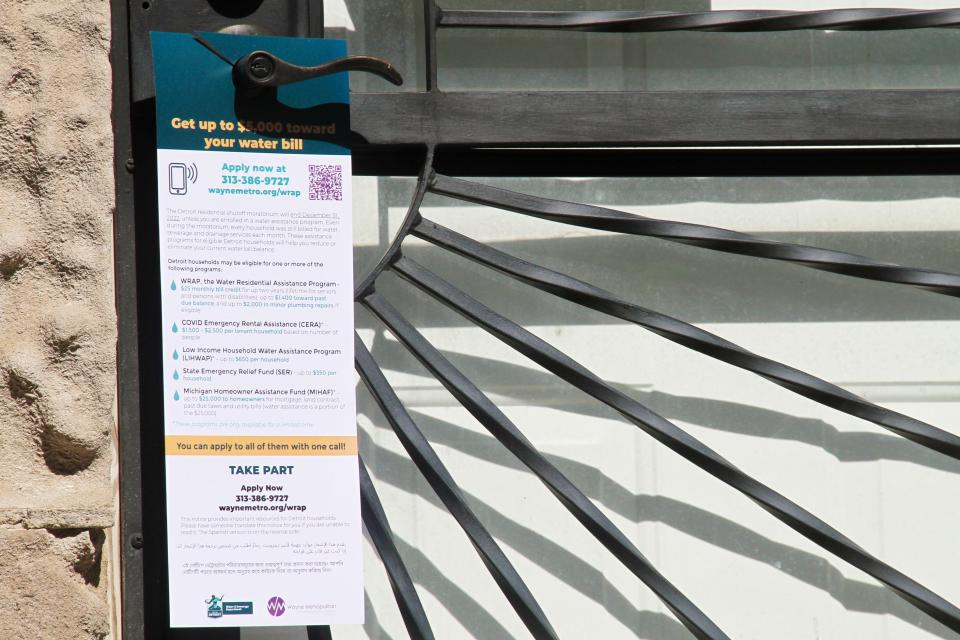

Brown stressed the city won’t turn off water to low-income residents who ask for help and the water department began an aggressive door-to-door outreach campaign in April to educate residents at risk of shut-offs about its debt assistance programs.

“We have dollars available so there's going to be no customer (of) DWSD that sees a service interruption because they can't afford to pay. That just can't happen,” Brown said. “We have the dollars available now. We're looking for a permanent solution so that they'll always be there. But right now, (the focus is on) getting people enrolled.”

The water department in January received a one-year federal tranche of $10 million for low-income households with delinquent water bills. There’s another $5 million in funding for WRAP, and another $5 million expected in July, Brown said.

Brown said he’s lobbied the governor’s administration and state lawmakers for a permanent funding stream, but Detroit representatives said those conversations are just starting. Brown hopes that he can prove the need for sustained funding by signing Detroiters up for the Low Income Household Water Assistance Program.

“Our goal is to show the state and the federal government that we can get Detroiters enrolled into these programs with the dollars we have on hand and that the program is worthy of being permanently funded,” Brown said.

Residents ‘antsy’ over large bills

More than 60,000 city households have delinquent water bills — an estimated 27% of Detroit’s 220,000 residential customers, according to DWSD. The average debt per customer is $700.

The city’s collection rate dropped from 93% at the start of the pandemic to 75% in April during the ongoing shut-off moratorium. Some advocates worry about bills piling up as the threat of mass shut-offs over nonpayment looms on the horizon.

Cecily McClellan, a founding member of We the People of Detroit, manages a hotline for the organization and said residents are getting “really antsy” because many have large water bills that they haven’t been able to pay down.

“They're still low income; income hasn't changed,” she said. “And they’re concerned about what's going to happen in December.”

Advocates also have questioned whether Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan will make good on his commitment to find a permanent solution.

“We have to fight to make sure that none of these situations arise again,” said DeMeeko Williams, chief director of Hydrate Detroit. “It's a public safety and human rights issue.”

Duggan told BridgeDetroit that the water department is aiming to have its plan out in July and reiterated the door-to-door campaign to inform residents. The mayor deferred comment on the water department’s efforts to engage water advocates to Brown. His department is working to set up additional meetings ahead of Wednesday.

The “lifeline” rate Brown intends to propose will link water costs to usage, but that doesn’t line up with the income-based rate structure long supported by researchers and water affordability advocates.

Brown said the rate plan would provide customers who use within 6 centum cubic feet of water — which translates to about 4,500 gallons — per month a “modest” rate decrease. Most residents (78%) use 6 centum cubic feet, he said. For those who use more, the rate would increase.

Customers would automatically be enrolled in the new rate Aug. 1 if it’s approved by the Board of Water Commissioners. Jonathan Kinloch, a member of the water board, said there would likely be lengthy discussion around a possible rate change, and couldn’t say how soon it might be voted on.

Brown said he also wants to enroll 20,000 households in WRAP by the end of the year. The program, he said, will reduce or eliminate arrears and for those who have “aged” out of WRAP after two years or were removed will be eligible to rejoin.

“This board stands ready to do whatever is necessary to bring about a water system that no longer becomes a burden on our residents who can't afford to pay,” Jonathan said.

State Sen. Stephanie Chang, D-Detroit, said the Legislature “absolutely has a role to play” in preventing water shut-offs and setting standards for affordability.

Chang has sponsored a handful of bills to prevent water shut-offs for certain groups, including seniors, pregnant women and parents of minors and to require water providers to disclose shut-off and rate information, and standardize municipal billing practices. The bills are in a legislative committee on environmental quality and have not yet received a hearing.

Since at least 2005, advocates have been pushing for income-based water rates. Philadelphia and Baltimore have adopted programs that charge residents based on their ability to pay. In Michigan, such a proposal faces legal challenges.

The Headlee amendment to the Michigan constitution and a 1998 decision in a case called Bolt v. City of Lansing has generally been interpreted to mean that water services should not be based on factors such as income or a person’s ability to pay, but rather costs of service. However there are differences of opinion, according to a 2016 report from a panel of experts seeking ways to address challenges to paying water bills and service shut-offs.

Chang and other Detroit lawmakers said they haven’t been involved in conversations with DWSD about its water affordability plan, but Chang wants the Legislature to take the lead on drafting legislation for a statewide affordability program, based on income, that preserves the right of municipal water utilities to set rates.

“We should pass legislation that allows the department to create the specifics of the program,” Chang said. “I would imagine that we would need something that is a little bit flexible, and that can change quickly based on what the needs are.”

The state, she said, also should step up to continue funding for the Low-Income Household Water Assistance Program after it expires at the end of the year.

Michigan received $36.2 million in emergency LIHWAP funding from the federal government. Brown said Detroit needs $10 million annually to keep it going. Chang said she doesn’t have a dollar figure for how much money the state could provide.

‘Disturbing’ lack of engagement

Several leading figures in the water affordability movement say they have been left out of discussions about the city's plan to prevent shut-offs when the moratorium expires on Dec. 31.

DWSD has scheduled conversations in recent weeks with some groups, but others said they’d been left out. Wayne Metro recently met with Hydrate Detroit and We the People of Detroit.

But Williams, who met with Brown last week, argues there should be a water summit among all the city’s water activists, Wayne Metro, the City of Detroit and other investors and partners.

“We need a grand meeting about this so that everyone is in the room and can give their feedback,” he said, “and not just split off certain advocates for one group to say ‘yes,’ and then for another group to say ‘no.’”

Leonard said the process thus far hasn’t been collaborative or allowed for meaningful engagement from the groups that have called for affordability for years.

“At the very least, from the outset when the mayor announced this was the goal, there should have been conversations almost immediately and at each step of development of the plan,” he said. “Where it’s going to lead to is most likely they are going to release some plan and there’s going to be some things missing that we want there and it’s going to lead to conflict.”

Brown acknowledged that the water department has to do a better job of getting community members involved and helping his department “identify those that are truly in need.”

Beulah Walker, chief coordinator of Hydrate Detroit, says her group — which will be helping to get people signed up for programs — has been tuned into the city’s long term plan because they regularly attend water board meetings. Walker says she’s supportive of the plan, but it comes after “community pushback.” Advocates have been at the forefront of solutions, she said.

Still, Walker worries about the moratorium ending and funding expiring. Assistance programs have also, in the past, been hard for residents to tap into because Detroiters might lack internet access.

“Residents have been burned so many times,” she said.

Monica Lewis-Patrick, president and CEO of We The People of Detroit, a grassroots community organization, met in late May with Wayne Metro and Hydrate Detroit over the city’s affordability proposal.

Lewis-Patrick said part of the plan would cap water payments for customers at 150% to 200% of the federal poverty line — or a family of four making between $41,625 and $55,500 — at no more than 1.8% of their income. During the meeting, officials also talked about a forgiveness strategy and ways to address minor plumbing repairs, she said.

The discussions were validating for Lewis-Patrick and others who have fought for decades for affordable water.

“I’m sure, hopefully, they have some shame in terms of how they tried to bastardize the movement for water justice,” she said. “It’s been the dogged commitment of activists and human rights advocates to hold space that water is a human right and to hold space that no one was ever asking for free water. We were asking for affordable water.”

The promises, she said, are being met with trepidation, but mostly with elation.

“I see this as a moment of celebration for a community that not only is well deserving of this reprieve but also has been the North Star to the nation. The nation needs to be moving in this direction,” she said.

Sylvia Orduño, an organizer with the Michigan Welfare Rights Organization and People's Water Board Coalition, has said it’s unclear who is involved in creating the plan to address water shut-offs after the moratorium ends.

It’s left some skeptical of whether the city will make a demonstrable difference on water affordability, she said. Orduño has not met with DWSD officials.

“Part of the frustration is that those of us who've been working on this for years weren't included, weren't invited, haven't been involved,” Orduño said. “And it's pretty disturbing to know that it's being done in a nontransparent public way.”

Peter Hammer, a law professor and director of the Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights at Wayne State Law School, described communication with the city as “radio silence.” He said advocates have strongly pushed for going beyond payment assistance programs as the city puts together solutions.

“Assistance is at best a form of a bandage that can buy time; if the rate base is not inherently sustainable by itself, then assistance is short-term at best,” Hammer said. “It's better than nothing, but it's not going to help anybody in the long-term. Moreover, the assistance programs are often difficult to administer and create arbitrary criteria that exclude folks so they're not necessarily universal or comprehensive.”

‘Why do we have to pay so much’

Jacqueline Taylor started falling behind on her water bills in 2016 after a hip replacement surgery left her in the hospital and in rehab for several weeks.

The Detroiter said she received a water bill for more than $1,500 when she returned home. Taylor, 68, believes she was overcharged while she was hospitalized and no one was in her northeast Detroit home, she said.

Taylor — who is on a fixed income — has struggled to bring down the debt she’s accumulated since then. She has had other bills to think about as well, and the cost of living is rising.

Taylor said she hasn’t paid her water bills in a couple months because her priority is fixing her leaky roof and applying for programs to help repair it. Her ceiling has caved in and it is bubbling. Two buckets replace a couch in her living room. Taylor is in “dire need” of a new roof, she said.

“People are struggling. If they turn off your water … you can't wash your body, you can’t cook, you can’t drink unless you get bottled water and I think it’s totally unfair,” Taylor said.

Taylor is a plaintiff in a 2020 lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union of Michigan and People's Water Board Coalition that says water shut-offs have, for years, harmed residents and calls for a long-term solution to the problem.

In 2014, Detroit’s shut-off practices drew international attention, spurring the United Nations to declare that cutting off water for those with a “genuine inability to pay” is a human rights violation. Six years later, advocates who pushed to end water shut-offs during the pandemic spoke in similar terms.

Before the pandemic began, Taylor said she lived without water for more than a year. She relied on bottles of water from a local community organization to bathe and cook as well as help from family members. Taylor counts herself fortunate because of the support system she has, but worries about seniors and other more vulnerable Detroiters.

"It's not just me that may be going through these things,” Taylor said. “There are others that are in worse shape.”

Around March or April 2020, her water was turned back on, she said. She’s paid $25 a month for her water bill under a pandemic-era provision. Taylor said the statewide emergency relief program brought her debt down a bit, but she still owes roughly $5,400 in water bills. According to DWSD, Taylor owes more than $5,700 due to nonpayment across several years.

“We're surrounded by water. Why do we have to pay so much for water? It’s unfair to people who are just barely making it,” Taylor said.

Affordability problems widespread

The average monthly bill for a family of three in Detroit is $81.62, which amounts to just under $980 annually. City water bills are calculated based on water usage, sewerage disposal, and flat service charges for water, sewerage and drainage.

One in 10 Detroit households spends more than a quarter of their income — outside of other essential expenses like food and utilities — on water services, a report from the University of Michigan, Michigan State University and consulting firm Safe Water Engineering found last year.

The report found water and sewer service affordability is a widespread problem across the state in both rural and urban areas, but rates in Detroit are much higher than state averages.

Water bills in Detroit rose an average of 2.9% each year over the last five years, according to DWSD. Annual rate hikes were even higher before 2016, often reaching double-digit increases.

Since 1980, the average cost of water service — drinking water, sewage, and storm water costs — in Michigan increased 188% when adjusted for inflation, compared to increases of 285% in Detroit, and 320% in Flint, researchers said.

Elin Betanzo, president and founder of the consulting firm Safe Water Engineering, said there are many reasons behind increases in water rates in Detroit. Among them: population loss, deterioration of infrastructure and debt related to loans taken out to do upgrades.

Kinloch,the commissioner on the Detroit water board, said drainage fees are the “biggest concern from both residents and businesses.”

DWSD charges property owners for every square foot of their property that’s covered by an impervious surface, which includes roofs, driveways and parking lots. Kinloch’s biggest question for proposed rate changes is whether it lowers the drainage fee.

‘We won’t be able to save everybody’

The water department hired Human Fliers, a communications and data collection company, for a door-to-door campaign that aims to reach 20,000 likely low-income households to inform them about water assistance programs.

On a recent afternoon, Human Fliers President Vaughn Arrington strode through neighborhoods along the Detroit-Hamtramck border, knocking doors and talking to residents about their options.

Arrington said the canvassing has revealed a few hurdles for organizers. Detroiters are generally wary of financial scams and start out distrustful and they are skeptical that going through an application process is worth their time.

Other complications are unique to each neighborhood. Arrington said residents in zip codes with a higher proportion of immigrants are less likely to answer the door since Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers stepped up deportation raids a few years back.

Canvassers also run into language barriers. Homes without an English-speaker are put on a list for canvassers who speak Arabic, Bengali and Spanish to visit again later, he said.

Leonard, of the law center, said it’s challenging to navigate assistance programs and some who are eligible won’t get it.

“They don't know about it, aren't able to navigate the process to get it, whatever the case is,” he said. “There are going to be people that have their water shut off that shouldn't.”

Brown said there are limitations in programs. Some might have specific income eligibility, require the resident to have arrears or be for weatherization and plumbing.

“They're just too many restrictions on the dollars to allow us to use them in the most efficient and effective way,” Brown said. “We've been working on trying to get some of the rules and restrictions lifted in order to be able to leverage the dollars in all the different buckets.”

There’s an urgency to the work, Arrington said.

Vulnerable people who put off several years of bills during the moratorium aren’t aware that it's ending, and he worries that homelessness and poverty will be on the rise when pandemic aid ends.

“It just brings on some new cluster of problems that we just started fixing,” he said. “We just started getting better and here it comes again. I know this is about to happen. We won't be able to save everybody. There's not enough money to do that.”

Keely Chaney, a resident in the Marygrove neighborhood on Detroit’s west side, said she’s come close to having her water turned off before, but so far has been lucky to avoid it. She didn’t know a moratorium on shut-offs was happening, let alone that it would expire this year. Chaney didn’t hesitate when asked whether water is affordable in Detroit.

Everyone knows it’s not, she said.

Correction: This story has been updated to reflect Jonathan Kinloch is a member of the Detroit Board of Water Commissioners. His title was misidentified in an earlier version.

Reach Malachi Barrett at mbarrett@bridgedetroit.com

Nushrat Rahman covers issues related to economic mobility for the Detroit Free Press and Bridge Detroit as a corps member with Report for America, an initiative of The GroundTruth Project. Make a tax-deductible contribution to support her work at bit.ly/freepRFA.

Contact Nushrat: nrahman@freepress.com; 313-348-7558. Follow her on Twitter: @NushratR. Sign up for Bridge Detroit's newsletter. Become a Free Press subscriber.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Detroit’s water shut-off moratorium is ending. Here's what it means.