Developer's vision of climate change hub on the Hudson seen as 'pie in the sky'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

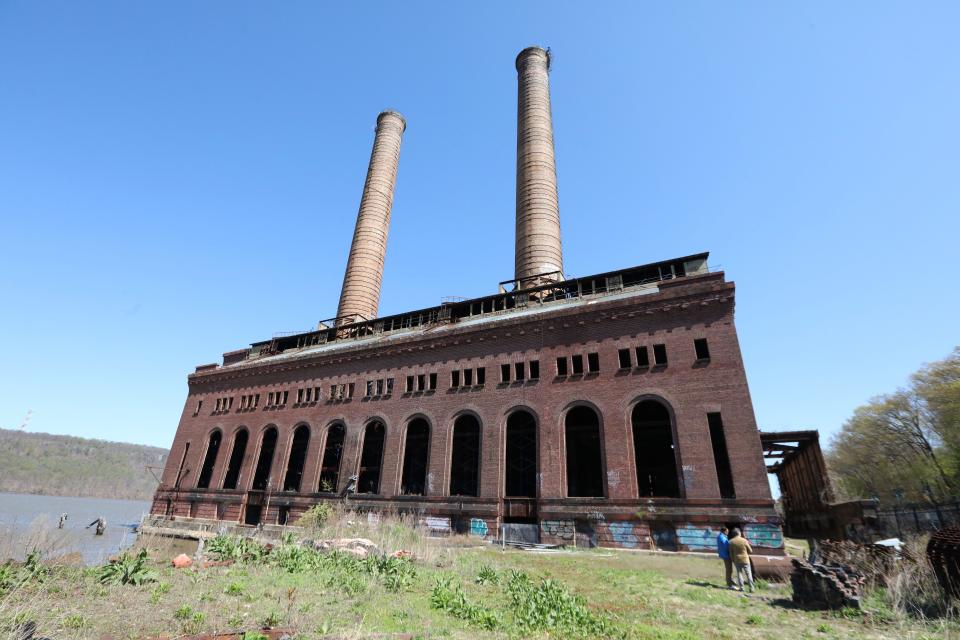

Lela Goren’s dream of transforming the long-vacant Yonkers Glenwood power plant into a center for climate change solutions has slogged on for years.

So far, it has gobbled up $25 million cleaning up the site and stabilizing the buildings as the plan wends its way through a thicket of government approvals.

Linked with the power plant plan is Goren’s long-delayed restoration of the historic Alder Manor two miles north. Together, the ambitious $240 million project called The Plant could turn the eyesore at the power plant and rundown mansion into destinations in New York’s third largest city.

Goren envisions transforming the massive power plant property into a co-working space with vast open areas for exhibits and events that serve to connect the climate change activists with scientists, corporations, innovators and artists.

Despite the distance, the historic Alder Manor is intended to provide lodging and ballroom space for those participating in events at the power plant, as well as for weddings and movie shoots.

“On a daily basis, through mindful design and operations, people will have access to inspiring spaces, convenings, financial resources, connections, healthy food, wellness, art and nature,” said Goren in a statement. “The Plant will be a hub of innovative activity and foster community.”

Benefits: Yonkers community says little progress on Glenwood community deal

Albany: State grant brings $1 million to Glenwood power plant project

State of City: 5 things to know about Mike Spano's 2022 speech

There's an aura of glamour and glitz around Goren. A video on the Goren Group's website shows her striding in heels and an ankle-length coat through the debris at the Glenwood power plant, proclaiming that "real estate development is an opportunity to create change."

Goren’s vision has captured the imagination of state economic development and energy officials, who have backed her with $4 million in state tax dollars. Goren has her sights on as much as $60 million in government support through state and federal tax credits for the restoration of historic properties and the cleanup of post-industrial brownfields.

But at this point, Goren may be the only one who sees a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

“I don’t think it’s real,” said Terry Joshi, of the Yonkers on Hudson Alliance. “I’ve been asking who is your anchor tenant and how do you pay your bills? There is no answer to that.”

And Yonkers Mayor Mike Spano, whose brother, Nick has served as a $5,000-a-month lobbyist for the developer on issues in Albany since September 2020, said he’s frustrated at the project's slow pace.

“Her plans are beautiful, but there would be a lot less frustration if the project moved a little quicker,” said Mike Spano.

Even Yonkers community activists and a local developer have questioned whether Goren’s mission-driven project has the financial wherewithal to succeed. They question whether Goren can marry the costly rehabilitation of two historic properties with her social activist goals.

Plans evolved almost a decade ago

Goren's involvement in the project dates back to 2013 when she partnered with developer Ron Shemesh in a company that purchased the vacant plant from another developer for $3.1 million.

In 2014, a corporation headed by Goren paid $5.5 million for Alder Manor, a 35-room early 20th century Italian Renaissance mansion built on Warburton Avenue by mining tycoon William Boyce Thompson.

By 2015, a new corporation led by Goren bought out Shemesh for an undisclosed sum, property records show.

Goren’s purchases of properties in Yonkers, either on the Hudson River or with views of it, are part of a land rush by developers in the metropolitan region who are looking to capitalize on the city’s proximity to New York City, and a municipal government determined to find uses for its vacant industrial buildings.

Goren calls herself both a developer and social activist. She said the concept for The Plant grew out of with her meetings with contemporaries in the climate and environmental justice movements. The plan emerged in 2018, five years after the plan conceived by Goren and Shemesh to build a hotel, art exhibition space and marina there died before gaining any approvals.

Goren this spring said she turned away an anchor tenant for the power plant because that would run counter to her theory that having a slew of small start-up businesses, nonprofits and artists in the building will create the synergy to spark action.

Former Yonkers City Manager Neil DeLuca, who went into real estate development after serving as deputy Westchester county executive in the 1990s, said Goren’s vision may sound good, but he wonders how her company can monetize it.

"You live and die from your anchors in real estate development," said DeLuca. "This sounds like pie in the sky."

The vision takes hold

Built in 1907, the plant provided electricity to New York Central Railroad and Grand Central Terminal for decades until it was shuttered in the 1960s. It has lain vacant since then, with its walls an ever-changing canvas for graffiti artists, and its environs a hangout for gangs in the 2000s, when it was called the Gates of Hell.

In May, Goren’s team won preliminary approval from the Yonkers Planning Board for the project, which will allow work to proceed on stabilizing the power plant buildings. On June 1, the state Legislature passed a state law to allow small pieces of Yonkers city parkland to be given to the developer to provide road access to the plant and proposed parking garage.

The bill, which awaits Gov. Kathy Hochul's signature, will also return to parkland nine acres by the plant that were once thought necessary for the project.

There's unresolved issues with the Metropolitan Transportation Authority as well. The project needs MTA permission for a walking bridge over the Metro-North tracks to connect to the city's planned parking garage on Warburton Avenue and a ramp from the Glenwood station platform.

There's also the need for access by emergency vehicles from the south along a narrow strip of riverfront land with MTA switching equipment.

MTA spokesman Dave Steckel said Goren had yet to submit plans for the bridge and ramp. As for the access road, Steckel said it was "not safe or feasible," which could present more engineering challenges for Goren.

Ray Ocasio, head of development for The Plant, said that discussions with the MTA continue.

"The MTA is actively seeking transit-oriented development, that's what we have here," he said. "We hope to come to an agreement."

State economic development officials remain optimistic about The Plant, saying it fits into the state’s vision for the Hudson Valley, providing financial support for destinations that draw tourists, and supporting clean energy and a cleanup of a long-vacant industrial sites.

“It fits into our strategic plans for the region,” said Kristin DeVoe, spokeswoman for New York state Economic Development. “It may be slow, but she has met the milestones for the funding.”

Goren has urged patience for her grand plans for northwest Yonkers, which entail the painstaking work of historic renovation of both sites, with construction done to top environmental standards as a showcase for the climate change work to be conducted within.

Goren responded to Spano's frustration by noting that the city of Rome was not built in a day. She predicted that The Plant will someday become a case study in how sustainable development gets done in the 21st century.

To finance her dream, Goren plans to rely upon a mix of state and federal government grants, tax credits for historic preservation and environmental cleanup, along with the backing from socially conscious investors, the state’s Green Bank, and up to $35 million in municipal revenue bonds to pay for a 506-space parking garage.

The Plant would guarantee any shortfall in parking revenues to meet annual bond payments, said Yonkers spokeswoman Christina Gilmartin.

Revenues for the project, said Goren, will come from corporate sponsorships, events, exhibits, start-up companies and memberships in the co-working spaces.

Goren says The Plant will “host” entrepreneurs in technology labs where they can test their concepts and pitch to companies. The free space would be sponsored either by a corporation looking to back innovation in its industry, as the car manufacturer Volvo has done in California's Silicon Valley, or through The Plant taking an equity share of the start-up companies in exchange for rent.

"Our business model succeeds as the collision of ideas between our members translates into new collaborative ventures and as movements and companies grow," she said. "Diversifying our members and avoiding anchor tenants allows for unique perspectives and inclusiveness, more ideas, and ultimately more opportunities for our members."

Goren said the space itself inspires, with its expansive views of the Hudson, soaring skylights bringing in light from 108 feet overhead, and the remnants of the fossil-fuel burning coal plant to remind those in the climate movement how far we have come, and how far we have to go.

“It’s remarkable, it’s magical,” she said. “When you go there, you really feel your biochemistry shifting. You feel like you are in a different era, and you are in nature. Because it’s an incredible site, it’s incredibly challenging, and it takes longer.”

The Plant represents Goren’s latest attempt to fulfill her vision of creating innovative real estate deals that reimagine historic properties into hubs with co-working offices, spaces for entrepreneurs and activists to convene meetings, as well as venues for artists and musicians to build community.

"We want to do development differently," said Goren. "You have no choice. You have to look at your internal operation, how you get your building green and sustainable and how you make people happy inside of it."

These projects grow out of Goren's work in the early 2000s as an intellectual property lawyer at the United Nations, which is sponsored by governments from around the world, and as chief development officer at the co-working company, We Work, in the mid-2010s.

"When I worked at We Work, we saw the power of bringing together community, with entrepreneurs and not-for-profits at lower rents," she said. "I take the concept of the United Nations, where the world comes together, and take what we learned at We Work, and try to figure out what to do with the buildings."

Yonkers community activists, however, failed to exact a promise from Goren's team on the magnitude of rent reductions for nonprofits and local vendors.

“They couldn’t agree to anything,” said Yonkers resident Christine Peters.

Going slow at Alder Manor

Meanwhile, the Alder Manor is seen as the basecamp for those filling up the plant. However, eight years after purchasing Alder Manor, the historic mansion’s $40 million makeover remains a work in progress.

In fact, final site plan approval for the historic renovation and the addition of the Cliff House ballroom and catering hall remain outstanding before the Yonkers Planning Board.

During a mid-April Planning Board meeting, board member John Larkin pointed out that the developer hadn’t been transparent about its plans for catering at the Manor. Larkin said they were originally told all the catering would be done offsite, only to learn later that Abigail Kirsch, the renowned Westchester catering company, would have a commercial kitchen at the Cliff House banquet hall.

He asked the developer be more forthcoming with information in the future.

“I don’t’ have any problem with any of this. It’s just that I feel we had to pull teeth to get information out of the applicant,” Larkin said. “Some of the information we’re getting is piecemeal, and it shouldn’t be that way. Or it’s late. Or it’s a few days before we have a meeting.”

The work has moved slowly.

Take the mansion’s slate roof, for which Goren obtained permits to redo in 2019. Three years later, it’s only 60% complete, with the work stalled by COVID-related construction delays.

The developer in 2019 demolished the former Elizabeth Seton College dormitory behind the mansion, which went up in the 1960s when the mansion was part of a private college campus. That demolition freed up the glorious view of the Hudson, and will provide space in its basement for the ballroom.

Brian Lindsey, the project's construction manager, estimated the Manor would be reopened in the summer of 2024.

Who is Lela Goren

Born in Israel, Goren, 52, emigrated to Long Island with her family when she was 5. She studied political science at the University of Wisconsin, then returned to Israel to earn a master's degree in law from Hebrew University in Jerusalem, where she also played professional basketball.

She returned to the U.S. to earn a law degree at Franklin Pierce Law Center in New Hampshire in 1999, according to a 2002 profile of Goren in the school's alumni magazine. At the time, Goren spoke about seeking a balance between the public and private sectors, as well as the creation of wealth and its redistribution.

She later moved into real estate, served as senior vice president at Extell Development in Manhattan before forming her own development company, the Lela Goren Group.

A look at her company's website details the aspirational vision for several projects, though only the renovation of her Greenwich Village townhouse on West 11th Street was completed. Her company's tagline: "Creating buildings that make change."

There are two previous Goren ventures that were never built with somewhat similar development philosophies to The Plant . A plan to transform the vacant Bayview Correctional Facility in Manhattan's Chelsea neighborhood into a center for women and girls, conceived in collaboration with a foundation run by Warren Buffett's son, Peter, was launched with great fanfare in 2015.

But the Novo Foundation, its principal funder, pulled the plug on the project in 2019, citing its spiraling costs.

In 2019, the Goren Group was part of a consortium that included the World Economic Forum, We Work and other mission-driven groups that proposed a plan to rebuild Fort Scott on federal land in San Francisco's Presidio neighborhood. But that plan was rejected by the Presidio Trust, in part, because it did not support the Trust's financial stability, underestimated security costs, and lacked an adequate transportation plan, according a Trust spokesperson.

Goren, the mother of three, acknowledged that the birth of The Plant has taken quite some time to get off the ground.

“This is like giving birth,” she said. “And this is like past the elephant stage of holding in a baby – a gestation period of 10 years.”

And at the pace so far, it’s uncertain just how long it will be before the The Plant comes to life.

Follow Tax Watch columnist David McKay Wilson on Facebook or Twitter @davidmckaywils1. He has written about Hudson Valley public affairs since 1986. Check out his latest columns at lohud.com

Contact Diana Dombrowski at ddombrowski@gannett.com. Follow her on Twitter at @domdomdiana

This article originally appeared on Rockland/Westchester Journal News: Lela Goren has sweeping vision for Yonkers power plant. Will it happen?