Type 2 diabetes rates plague this county. How solutions are growing in a broken system.

Editor's note: Part two of a five-part USA TODAY series revealing why America hasn't solved its long struggle with Type 2 diabetes.

MILESTON, Miss. – Calvin Head swung his hoe with every step as he paced the neatly furrowed rows. Each slap carved a dent into the sandy soil.

Following behind, four younger workers dropped 6-inch-tall tomato plants into the holes Head had made and then carefully mounded the earth around each, so they’d stand straight.

The team was eager to get them into the ground before the next day’s predicted downpour.

They expected a lot from these tiny plants.

The tomatoes, along with the cantaloupe, cucumbers and cabbages they planted nearby, will provide local residents with fresh produce – which is otherwise hard to get in this patch of the Mississippi Delta.

Farmland stretches across the horizon, but almost none of the industrially grown corn or soybeans is intended for the local market.

That’s one of the reasons Mileston and the other communities in rural Holmes County, population 16,000, have among the highest diabetes rates in the nation.

About 1 in 10 Americans has diabetes. In Mississippi, which has one of the highest burdens of any state, it’s closer to 1 in 8. In Holmes, 1 in 5 has the disease.

Many factors drive these rates. It isn’t easy to afford groceries, access quality medical care or get enough exercise. Shopping is an expedition. Seeing a specialist is a daytrip.

The Diabetes Dilemma

Type 2 diabetes rates continue to climb, despite well-known treatments and prevention approaches. To better understand why, USA TODAY's health team traveled across the country, talking to researchers, clinicians and patients. They found people with diabetes often must fend for themselves against systemic barriers and a difficult disease.

There are no sidewalks, so a pedestrian would have to share country roads with semis, tractors and logging trucks. Mileston’s lone walking trail, a loop alongside a former elementary school, isn’t shaded by a single tree.

Local watering holes don’t offer any exercise opportunities, either. They’re teaming with alligators.

But from farm fields to pulpits, medical clinics, radio booths and the auditorium of a museum honoring blues great B.B. King, residents like Head are doing what they can to improve the health of their neighbors and themselves.

“This is the way things are. But this is not the way things have to be,” said Head, who helps run the local farming cooperative. “If we can create opportunity, we can dig ourselves out of this mess.”

The way things used to be

When Head was a boy, he could get his fill of fresh berries just by walking down the road. Roses and honeysuckle scented the landscape. Every yard had a garden, and fig, walnut, apricot and other fruit trees were plentiful, he said, smiling at the memory of biting into a fresh pear, juice dripping down his face.

Pesticide spraying by the industrial farmers has ended most of that diversity, along with the lightning bugs, crickets and pollinating bees. “They killed everything trying to get rid of the boll weevil,” he said. “They’re slowly but surely killing us.”

More in series: American can prevent (and control) Type 2 diabetes. So why aren’t we doing it?

Now, nearly everything people eat here comes with a barcode or on a Styrofoam plate. A bag of chips is cheaper and easier to find than a bag of carrots.

History, both good and bad, hangs heavily over this tiny town, miles from the nearest stoplight.

Black farmers bought land after Emancipation, but many were forced into sharecropping because of economic hard times and racial prejudice. Records show 11 Black people were lynched in the county between 1877 and 1950.

Then, under the New Deal, the government provided Black farmers with low-interest loans to purchase 10,000 total acres of farmland and establish the Mileston Cooperative, one of 13 cooperatives in African American communities nationwide. Of the initial 40 Mileston Co-op families given land nearly a century ago, the land is owned by descendants of all but one of the families, Head said.

The community raised money for a school and a health clinic. There was once a post office here and the first Head Start early childhood program in the region.

A historical marker sits across from a former gas station that marks the center of town. It notes the cooperative and the role community members played in pushing for voting rights and civil rights in the 1950s and 1960s. Head’s mother Rosie is one of four residents listed.

In the mid-1990s, 14 descendants of the original cooperative members, Head among them, began to revitalize the defunct organization. He has helped run it ever since.

At 60, Head takes pride in still being able to outwork men half his age. Despite the heat and dust, his polo shirt and jeans look fresh. He groans at the constant buzzing of his cell phone and quickly makes his apologies when a caller interrupts his farm work.

Another coop member furrows the fields and a motorized tiller helps cut up weeds. Otherwise, everything is done by hand.

Workers Rico Washington and Antonio Row, both 29, have known each other their whole lives. “High school, elementary school, preschool,” Washington said. On farm fields, they good-naturedly tease and pick on each other.

More in series: A diabetes disparity: Why Colorado's healthy lifestyle brand isn't shared by all

Head sees the 11 acres he manages on the cooperative farm as a way to offer opportunities to men like Row and Washington, who otherwise would have few opportunities or reasons to stay in Mileston.

Over at the elementary school the county closed nearly a decade ago, Head and his team have filled the former gymnasium with rows of grow lights in preparation for planting season. In a classroom down the hall, they’re testing different amounts of nutrients, looking for the most effective way to germinate tomato plants. Formulas for maintaining proper temperature, water quality and pH balance cover the blackboard.

Washington took a class in hydroponics to help lead the effort. He likes the outdoor work with Head – “whenever he calls, I come out and try to help” – but is happier with hydroponics indoors where it’s cooler.

They grow some plants completely indoors to protect from the pesticides. Hydroponics also provide a hedge against bad weather, like the flooding that ruined local crops for three years in a row and the hailstorm that would ruin this year's spring crop. Others will be germinated here and then planted on some of the 2,800 acres the cooperative controls across Mileston ‒ once they manage to finally install solar roof panels on the school's roof to provide affordable electricity.

Head has other plans, too: to create 12 jobs in the hydroponic center, to open a produce store at the former gas station with eight to 10 more jobs, and to send food to state shelters. He thinks he can even compete with California. The soil here in the delta is perfect. "It can produce almost anything," he said.

Showing off the rows of hydroponic lights, he said, “we’ll have a continuous flow of produce whether it’s raining, snowing or sleeting outside.”

“Hopefully, some of the produce we grow will help offset some of the health issues, not just diabetes, but malnourishment and hunger.”

Filling a medical desert

Not many doctors want to move to this rural area. Even Jackson, the state capitol, struggles to attract specialists. Despite having the among the highest rate of diabetes in the nation and a population of 3 million, the entire state of Mississippi has only 22 diabetes specialists, according to the Endocrine Society, a professional medical organization.

In 2020, the state’s life expectancy fell to 72 years, five years below the national average. That was before the pandemic, which likely cut it further.

When he returned to Mississippi after a medical residency in New York City, Dr. Rozell Chapman was the first pediatrician in Holmes County in nine years. He came back to try to help.

Now he heads Mallory Community Health Center, with two facilities in Lexington, the county seat, as well as one in Tchula, on the county’s west side and three other spots in the region. Helping people make even little changes will benefit their health, he said, citing one of his patients who agreed to eat just one bologna sandwich a week, instead of three a day.

“You have to meet people where they're at and and just try to find the best way to support them and help them grow,” Chapman said.

The health statistics in Holmes County are sobering.

The average age here is 36, but diseases more typically associated with seniors are common. High blood pressure, high cholesterol and diabetes are the trifecta, all well above the state average, along with obesity, state data shows.

“Young 36-year-olds are dying from cardiovascular disease. What does that do to their family? The children that they were bringing up?” Chapman said.

The statistics aren’t simply the fault of bad habits. The rate of smoking and drinking is lower in Holmes than elsewhere in Mississippi and there’s a higher reported rate of exercise than in the state overall.

More in series: The steep cost of Type 2: When diabetes dragged her down, she chose to fight

People pay Mallory on a sliding scale, but even the cheapest copay of $20 can be a challenge, so many wait until they’re in a crisis to seek medical care. The closest hospital is in Greenwood, 30 miles away, though it's in danger of closing and has already shuttered its maternity an intensive care units.

Community health clinics like his own are collaborating across the state to try to improve medical care, Chapman said, but more resources would be great. Mississippi is one of 10 states that has not expanded Medicaid coverage under the Affordable Care Act, so many people with modest incomes still don’t have federally funded health insurance.

“Expanding Medicaid would be phenomenal,” Chapman said. ”To get the access to those people that need it the most.” He hopes that “soon we'll see eye to eye” with state legislators and “be able to help the residents of Mississippi.”

Honoring a blues legend with education

An hour northwest of Chapman’s clinics, in Indianola’s B.B. King Museum and Delta Interpretive Center, diabetes also tops the agenda. Blues great and native son B.B. King coped with diabetes for the last 25 years of his life. He was open about it and appeared in commercials for a blood glucose monitoring device that allowed the guitarist to avoid pricking his fingers.

The museum opened in 2012, three years before King’s death. It honors his fight against diabetes by holding information and cooking sessions on the fourth Thursday of every month. As of early May, more than 200 locals had attended this year.

Gift-shop manager Roshanner Jennigan prepares meals low in sugar, salt and fried foods. Misty Clark-Johnson, the museum’s education director, arranges for dietitians and others to educate participants.

“Everyone thinks that once they have a diagnosis of diabetes, it’s a life sentence,” Clark-Johnson said. She tries to show them that’s not true. “You can still live a long healthy life, just by eating right, exercising, changing the little stuff in your lifestyle.”

More in series: Solutions exist to end the Type 2 diabetes dilemma but too few get the help they need

Last year, she added a program for children ages 8 and up with Type 2 diabetes. Type 2 used to be called “adult onset,” but more young people are developing it, typically because of unhealthy eating.

One student has been coming every month and her diabetes has stabilized. “I know I’m making a difference,” Clark-Johnson said proudly.

The programs are grant-funded and free for participants, in a community where the median income hovers around $20,000 and many folks are older or single parents. A free meal is a great enticement. Offering a social opportunity and diabetes education adds to the benefit, said Malika Polk-Lee, the museum’s executive director.

“We as a community are trying to do what we need to do to help solve the problem,” she said.

Delivering a message of hope

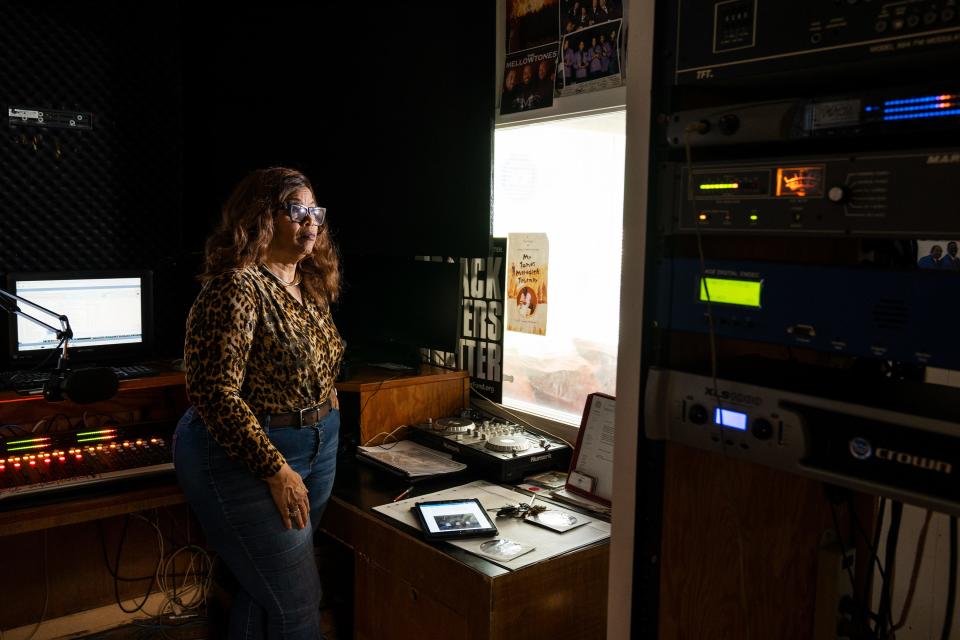

“Good morning! Good Morning!” Shella Head exclaimed at the start of a Saturday morning live radio show in May, her hands shaking slightly with nerves. A career state official whose ex-husband is a distant cousin of Calvin Head’s, she opened by promoting a local insurance company. Pitching helps defray her public service show’s $100 weekly cost.

Reading from a stack of papers she’d brought, Shella Head let her listeners know about a fight between cousins that led to one of the county’s few murders. Next, she spotlighted a program to help students with low grades attend college.

Her program airs on WAGR-FM and WXTN-AM, once country- and Christian-focused and owned by the daughter of a Ku Klux Klan Grand Wizard. Under the direction of station manager Isaac Lindsey, Praise In the House Radio’s programming is now mostly gospel and blues, with some service programming like Head’s, aimed at the region’s many Black residents.

About 10 minutes into her morning show, Head pivoted.

“Let’s talk about obesity,” she said. “I’m blessed with my grandmother’s hips, but everything else is on me.”

Her careful curls draping onto a leopard-print shirt, she listed the health troubles that can come with excess weight: Cancer, kidney disease, thyroid problems. “All types of issues all over your body.”

Culture plays a role, too, she noted. In her community, being somewhat overweight by medical standards is considered healthy. “If I weighed what they think I should weigh, somebody is going to think I got something wrong with me,” she told her listeners.

Head clasped a package of chicken-flavored ramen noodles she’d brought to the studio.

These ramen noodles have a whole day’s worth of sodium, she said, her voice rising. But they’re “hardly nothing” on the plate. She held up the package to show her Facebook Live audience. Most people add something on the side, like meat and bread, maxing out their safe amount of daily salt in just one meal.

“We’ve got to change the way we eat!” she said.

Fifty minutes after she began talking, Head signed off. “You all be safe out there and be blessed!”

Serving up healthy meals on Sundays

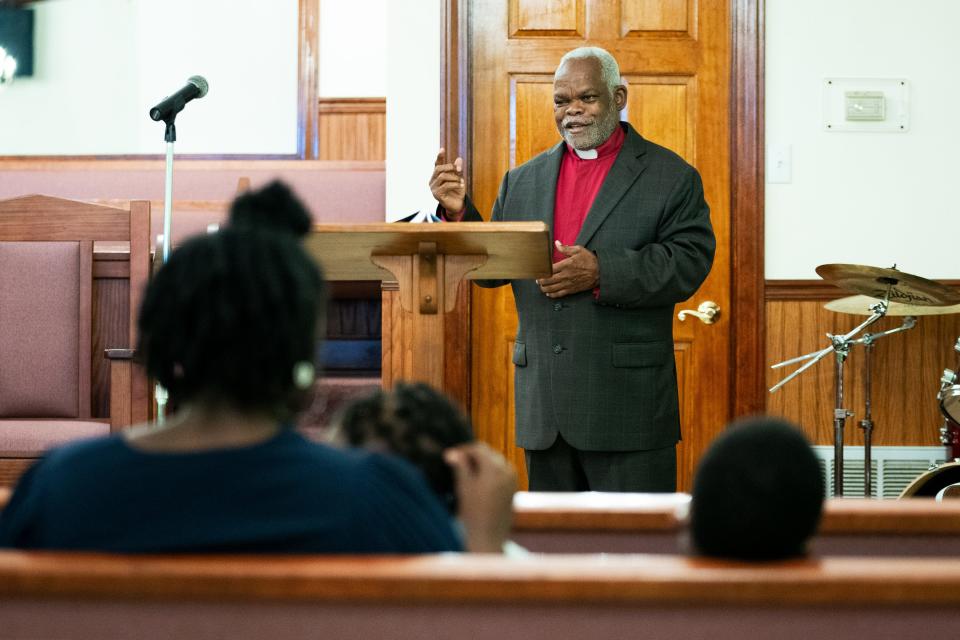

The next morning in Tchula, in the western part of Holmes County, the Rev. Tom Collins, 69, preached love, the glory of God, and the importance of a healthy lifestyle.

For 23 years, he’s been at the helm of the Bethlehem Baptist Missionary Church, located a few miles north of his home.

“When we’re serving one another, we’re serving God,” Collins said from the pulpit.

“That’s right,” responded Calvin Head, his brother-in-law, sitting in a back pew.

Collins led an hourlong service punctuated by a few rousing hymns and a short sermon. “I’m not a long-winded preacher,” he noted. Afterward, he and his wife Dolly, Calvin’s sister, typically host a weekly Sunday dinner for their extended family.

The couple met in high school and have been married for 46 years. Dolly, a soft-spoken first grade teacher – and a “health nut,” Tom said affectionately – insists on homemade food with limited sugar, salt and fat.

That Sunday, the house buzzed with activity while the food baked. Some rested in the comfortable couches and chairs in the living room; others on the front porch, children dashed in between.

Collins, his face encircled with white hair and a close-cropped beard, apologized that the offerings were more limited than usual: just purple hull peas, baked sweet potatoes, corn-on-the-cob, pork chops, hot-air fried chicken, corn bread, salad and his special collards, made with smoked turkey instead of ham hocks.

Collins has been committed to healthy eating since the day in 2016 when his vision turned fuzzy. “Then all of a sudden, it was like looking through a dirty window.” He couldn’t keep down food or water. His sister drove him to the nearest hospital, 30 miles away.

The doctor came in and, without saying a word, put Collins in a wheelchair, wheeled him into a room and started hooking him up to tubes and monitors. “That’s when I knew I was in trouble,” Collins said. “I thought I was going to die. I really did.”

He was diagnosed with diabetes and took the threat seriously. An education class taught him about the disease and how to eat better. He transformed his diet.

He used to be a “junk food junkie,” piling up his plate with extra helpings of everything. Now he’s satisfied with smaller portions and has gotten used to new foods. “I used to hate – what do you call it? Broccoli. Now I love it."

“Daddy Tom,” as his daughter-in-law calls him, has a riding mower, but he cuts his neat lawn with a push mower for the exercise.

Collins also takes a weekly injection of the diabetes drug Ozempic.

His efforts have helped him shed pounds – he’s down to about 160 from around 200 – and drop his A1C level, a measure of diabetes severity, from over 7% to a healthier 5%.

Portia Collins, 36, married to the Collins’ younger son, Mikhail, has also tried to change her diet and exercise more since being diagnosed with pre-diabetes, high cholesterol and high blood pressure.

“I've got to do my best to take care of myself,” Portia said, pointing to her rambunctious 5-year-old daughter, Emerie. “I don’t ever want to be a burden on her. I don’t want her to have to take care of her mom because her mom wasn’t taking care of herself.”

Concerns for his family and young people motivated Tom Collins to participate in the Mileston Cooperative, where he keeps the books and does anything else that’s needed.

"I don’t want to pop open a can or pull out a Spam or something. I want some food,” he said. “And so that’s what we are trying to do.”

This story is part of a reporting fellowship sponsored by the Association of Health Care Journalists and supported by the Commonwealth Fund.

Contact Karen Weintraub at kweintraub@usatoday.com.

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Diabetes runs deep in Mississippi. Residents work to end the legacy