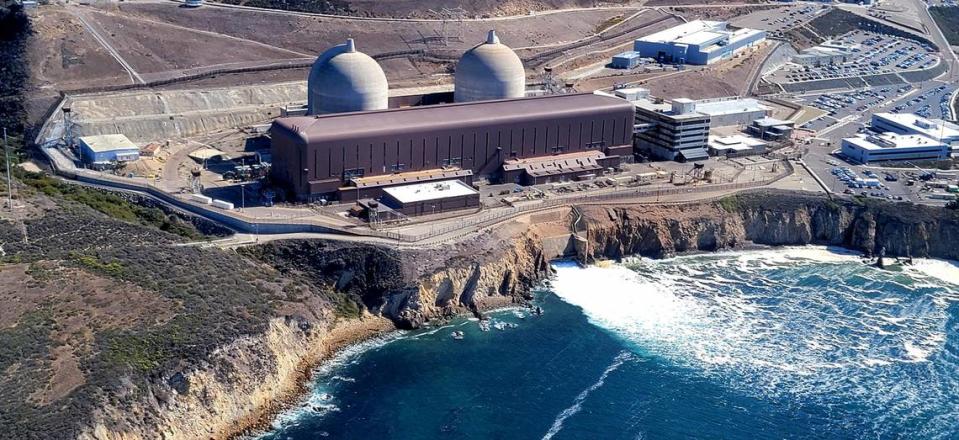

Diablo Canyon just got a $1.1 billion boost. Now how about a home for its nuclear waste?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The announcement of a $1.1 billion federal grant to keep Diablo Canyon up and running underscored the Biden administration’s support for nuclear power — and brought the plant one step closer to extending its operating life for at least another five years.

But as the U.S. turns to nuclear power to keep the lights on, will President Joe Biden and his successors be equally committed to securing a permanent home for the nuclear waste generated by commercial reactors?

That was a promise first made to residents of San Luis Obispo County more than 50 years ago, when PG&E assured skeptical residents that they needn’t worry about spent nuclear fuel because the federal government would take care of it.

For a while, it looked like it might even happen. Yucca Mountain, Nevada, was the designated safe haven for all that waste — until it wasn’t.

The Obama administration rejected the proposal, and while Donald Trump tried to revive interest in the site during his presidency, he abandoned that idea in the hope of wooing voters in the run-up to the 2020 election.

“Nevada, I hear you on Yucca Mountain and my Administration will RESPECT you!” he tweeted.

Consent-based siting is back

President Biden has returned to the Obama administration’s policy of focusing on establishing interim consolidated storage facilities, rather than a single permanent storage site like Yucca Mountain.

The locations for temporary storage will be chosen through a consent-based siting process. In other words, communities will only be considered as potential locations if they agree to “host” a dry cask storage facility that would accept spent fuel from numerous commercial reactors.

The government is investing big bucks in the program; $16 million has been set aside for communities interested in “learning more about the consent-based siting,” according to a September news release from the Department of Energy.

Up to eight applicants will be selected to receive grants, which works out to $2 million each for communities willing to consider the possibility of accepting spent nuclear fuel.

In theory, it sounds like a great tool.

No more top-down decision-making using an old-school process that’s been described as a “decide-announce-defend” model that works like this: Government makes a decision, announces it to the stakeholders, then proceeds to defend it.

Instead, communities are included in the process from the beginning, rather than having a decision thrust upon them — something especially important given that tribal lands and low-income communities have often been selected as sites for potentially hazardous projects, with little say-so from those most affected.

‘It belongs in a deep geologic repository’

Still, it’s hard to believe that communities would voluntarily agree to serve as even a temporary repository for spent fuel — especially since a permanent storage site is not even on the horizon.

Even conservative Texas Gov. Greg Abbott is against the idea — at least when it comes to allowing a facility proposed in St. Andrews, County, Texas.

“This deadly radioactive waste — up to 40,000 metric tons of uranium — would sit right on the surface of the facility in dry cask storage systems. Spent nuclear fuel is so dangerous that it belongs in a deep geologic repository, not on a concrete pad above ground in Andrews County,” Abbott wrote in a letter to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

He went on to say that the facility would be “a prime target for attacks by terrorists, saboteurs, and other enemies.”

The NRC issued a permit for the facility anyway, though it’s now tied up in litigation.

That’s a preview of what could happen with other such proposals, whether or not they’re “consent based.”

California’s moratorium

The state of California must have seen all this coming. In 1976, it imposed a moratorium on the construction of new nuclear plants until such time as the federal government makes good on its promise to accept the spent fuel.

But where does that leave Californians living in the vicinity of Diablo Canyon, or near shuttered plants like San Onofre, located close to San Diego?

They are exactly where they’ve been for the past five or six decades: serving as de facto spent nuclear fuel storage sites, without ever having the benefit of the consent-based siting process.

That may not change any time soon because, frankly, the storage issue isn’t top-of-mind for many lawmakers in Washington, D.C., unless they happen to represent a nuclear community.

Newly reelected Rep. Jimmy Panetta, whose district now includes northern San Luis Obispo County, acknowledged as much when he met with The Tribune Editorial Board during the recent campaign.

“I’ll be honest with you, I have not looked into that. But I look forward to doing that and getting back to you,” he said.

Rep. Salud Congressman, whose district includes Diablo Canyon, was better informed but not especially optimistic.

“Certainly, nobody wants this waste in their backyard, including here on the Central Coast,” he told the Editorial Board.

Priority for decommissioned sites

Carbajal serves on the bipartisan Spent Nuclear Fuel Solutions Caucus co-chaired by Rep. Mike Levin, whose district includes the San Onofre nuclear plant.

Levin has introduced legislation that would be especially beneficial to his constituents: a bill that would prioritize acceptance of waste from plants that are already decommissioned or in the process of decommissioning; are in highly populated areas; are located in high seismic hazard zones; and where continued storage presents a national security concern.

That leaves Diablo Canyon out of the first round — should there ever be a first round.

Levin also introduced the 100-Year Canister Life Act, which would require new spent fuel storage canisters to be built to last for 100 years, rather than the current 40.

That makes sense, given the length of time it’s taking to make any progress at all; for every single step forward, we seem to be taking two steps back — at great financial cost to taxpayers.

Meanwhile, other nations are moving ahead.

Finland is in the process of building a deep geologic repository to serve as a permanent storage site, and several other nations are far along in the site selection process, using the consent-based method.

There is no excuse for the lack of progress in the United States, especially given the renewed interest in keeping plants like Diablo Canyon running.

Political leaders have been content to leave it to future generations to figure out what to do with spent fuel that will need to be kept safe for tens of thousands of years.

That’s grossly unfair to citizens of communities like San Luis Obispo County, whose citizens were assured that a solution would be forthcoming.

It’s even more unfair to future generations stuck with the consequences of yet another short-sighted decision by those who should know better.

The question of what to do with spent nuclear fuel has been back-burnered long enough. It’s time for Washington to move the issue front and center instead of passing it on from one administration to the next.

If current leaders lack the political maturity to deal with the situation — and so far that appears to be the case — then nuclear communities must hold them accountable for finding a safe and permanent location for storing spent nuclear fuel.

Remember the words of Gov. Abbott: “Spent nuclear fuel is so dangerous that it belongs in a deep geologic repository, not on a concrete pad above ground.”