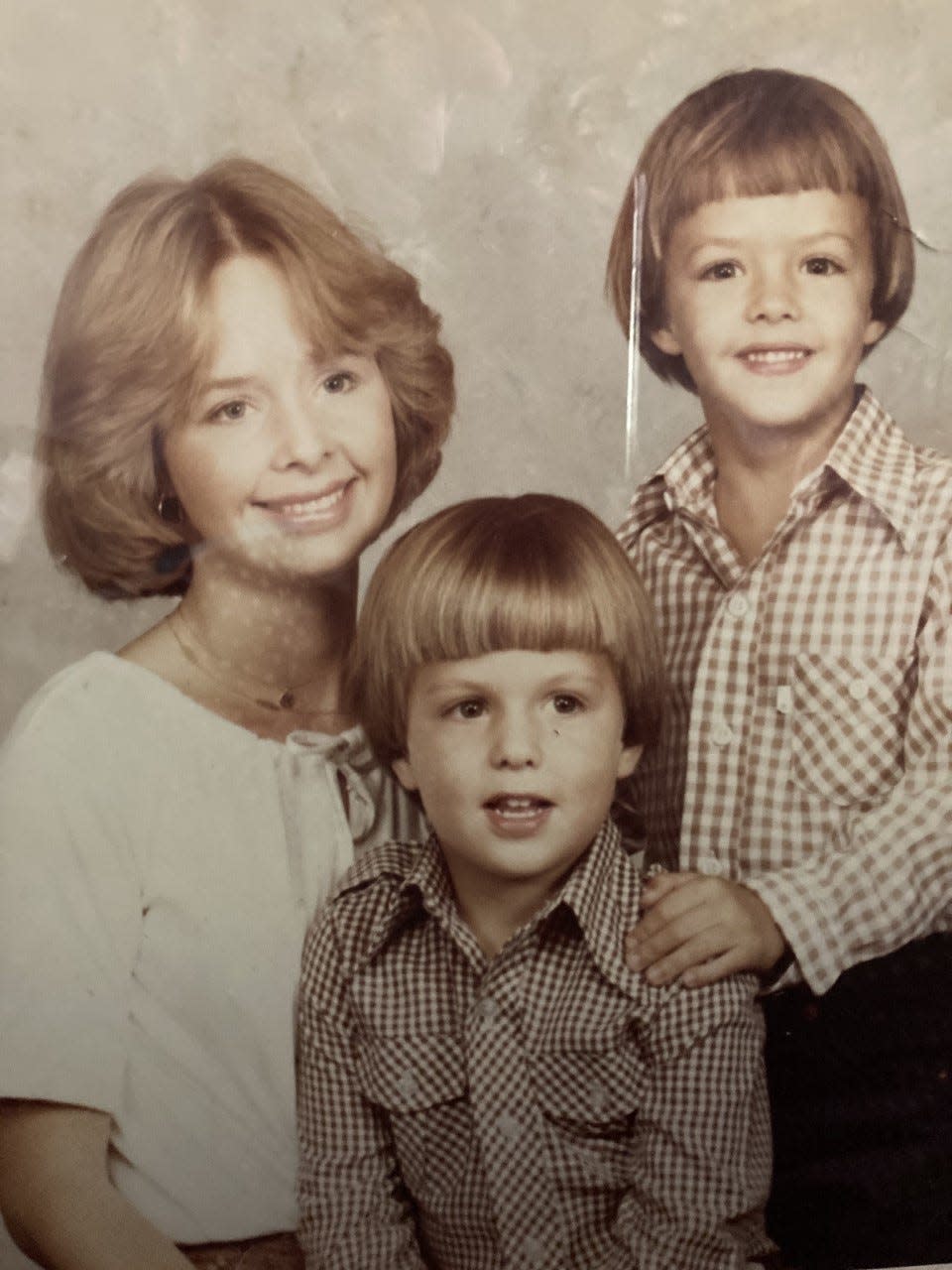

Dianna Phillips lived a full life fighting the disease that claimed both her sons

Although Dianna Phillips experienced tragedies in her 75 years, her life was anything but tragic.

It was filled with laughter and learning from the second graders she taught at White Bluff Elementary School, the loyalty and devotion of many friends, thought-provoking Bible studies and Sunday school lessons at Isle of Hope United Methodist Church, delicious smells and tastes coming from her accomplished kitchen, and wonderful memories shared with son Chris, his wife, Lucil, and their two daughters, Jolie, 12, and Mia, 11.

More: Contrast-enhanced mammography another diagnostic tool for breast cancer

“Dianna is a very special person,” says her daughter-in-law, Lucil Phillips. “There are many lessons to be learned based on her life. She has a beautiful soul. Because of her, I feel much more lucky, more blessed.”

This, despite the fact that both of Dianna’s sons died of Adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD) 38 years apart. The disease that took her sons usually presents in childhood, progresses rapidly, and causes deterioration of the brain. Her youngest, Creighton, died at age 6 in 1980 after being ill for two years. Her older son, Chris, had a milder form of the disease and did not begin to experience symptoms until his late 20s, when his mobility was affected. He died July 5, 2018, at age 47.

Dianna had the adult version of the disease, Adrenomyeloneuropthy (AMN), which presents later in life and primarily affects the spinal cord.

She had been under Hospice care for several weeks before her death on Saturday.

A hereditary condition

ALD is a rare, inherited disease that occurs in 1 in 20,000 births and is most commonly found in males. It affects the nervous system and the adrenal glands. It is incurable and there are no treatments. The disease prevents the cells in the brain from sending signals to other parts of the brain or body. It causes weakness and stiffness of the lower limbs that get worse over time.

Some people also experience speech or sexual problems, bladder control issues, nausea and weight loss. If the disease involves the brain, there can be behavioral changes, changes in thinking, vision or hearing loss, and seizures.

Letter: With Medicaid expansion, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure

The condition was the focus of a 1992 movie, Lorenzo’s Oil, based on a true story of a boy named Lorenzo Odone and his parents’ fight to save their son. Their tenacity led to the development of Lorenzo’s Oil, a combination of erucic acid and oleic acid, which is still used as an experimental treatment to slow the progression of the disease. Lorenzo Odone died of pneumonia in May of 2008 at the age of 30, two decades later than doctors had predicted.

Illness was not on Dianna Dubree’s radar when she was growing up in Marietta, Georgia, the middle of three sisters. She graduated from Marietta High School, and earned an elementary education degree from Mercer University in Macon. There she met handsome and personable Savannah native Bobby Phillips, who received an AB from Mercer in 1968 and a Juris Doctorate in 1970. Dianna and Bobby married in March of 1968, and she taught at Morgan Elementary in Macon while Bobby completed his law degree.

After graduation, Bobby joined the U.S. Army and the couple moved to Stuttgart, Germany, where Bobby served for four years in the Judge Advocate General Corp (JAGC), the Army’s legal arm. While in Germany, Dianna and Bobby had two sons, Chris in 1971, and Creighton in 1974.

In 1974, the family returned to Savannah, where Bobby practiced law and Dianna raised her boys. When Creighton was 4, his preschool teacher contacted his parents and said she believed Creighton was having vision problems, as he was using one arm to guide the other one to a box of crayons. They took him for a vision exam, and were told that the issue wasn’t his vision, but was a neurological issue.

Physician: COVID-19 pandemic lessons should spur Georgia General Assembly to action

That began a search for what was wrong, and the terrifying diagnosis of ALD. Things went downhill rapidly, despite their efforts to pursue possible treatments, including consultation with Dr. Hugo Moeser at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, whose work with ALD was featured in "Lorenzo’s Oil."

Creighton died at age six on Dec. 22, 1980.

“That’s the tragic part of the disease,” explained Dianna’s long-time church friend Sally Scott. “The doctors are really just checking on the decline. There is nothing they can do.”

Dedicated to teaching

Despite Creighton’s diagnosis, Bobby ran for and won a seat in the Georgia House of Representatives, serving from 1979 to 1984. Creighton died not long after he took office. The loss took a toll on Bobby and Dianna’s marriage, and they divorced in May of 1985. Shortly thereafter, Dianna was diagnosed with breast cancer.

But the thing about Dianna Phillips is that despite these major traumas, she maintained a positive attitude about life and a steady faith that amazed her friends. They used adjectives like “courageous,” “determined,” “fiercely independent,” and “faithful.”

More: 'Tasha' Holliman's voice silenced far too soon by aggressive breast cancer

“Her focus has always been on what she could do for somebody else,” Scott says. “I have never heard her talk negatively about Bobby. In fact, when he remarried and had a child, Dianna babysat so they could go out. She said that the baby was Chris’ half-brother, and she never wanted him to not feel welcomed in her home. That’s just the kind of grace she has. I know that both of them would stop a train for each other.”

After the divorce, Dianna started teaching in public school, first at Juliette Low and then at White Bluff, where she met Jane Anderson, a third-grade teacher. They taught all day and attended night classes at Armstrong State University, both earning master’s degrees. Many Friday nights, they’d stop for dinner on the way home.

Radiologist: Mammography saves lives by identifying breast cancer during screenings

“Dianna was a great teacher, and still talked about her students. I learned so much from being around her. The main thing was to be kind. She was always so kind. And strong. She had such a deep faith. She was a great cook," Anderson said.

"For my birthday one year, she told me to invite four people and she cooked dinner for the six of us – crab and shrimp and potatoes and green beans and dessert. It was all delicious. Her lemon bars were so good, and that’s what she’d bring when we were asked to bring a covered dish.”

A second journey

Meanwhile, Dianna’s surviving son, Chris, was thriving. He had a happy, healthy childhood, cavorting with his neighborhood buddy Daniel Sims. He attended Hancock Day School and Hesse Elementary until 6th grade and graduated from Savannah Country Day in 1989. He received an undergraduate degree from Northwestern University, and practiced accounting after obtaining his CPA certification.

He returned to school to study law at the University of Georgia and was admitted to the bar in 2002.

Mark Murphy: A toothache threatened my trip to the watch the Bulldogs in the College Football Playoff

In his late 20s, he began to experience difficulty with mobility. As his gait became worse, he opted for a wheelchair to get around more efficiently. Yet, he lived a full life – serving as staff attorney for bankruptcy judge Lamar Davis in Savannah before joining an Atlanta law firm, where he specialized in bankruptcy law. In Atlanta, he participated in wheelchair sports, including tennis and marathon events. He loved to travel, going to Europe solo after college and meeting friends there, where they survived for months on cheese and crackers and the kindness of strangers and saw the world.

In 2007, Chris met Lucil Truong, a native of Vietnam, and proposed on a trip to St. John, Virgin Islands. They married in 2008, and then along came Jolie and Mia, to Dianna’s delight. Her favorite job was being a Mimi.

“We had two beautiful children and we carried on a normal relationship,” explains Lucil. “It was short, but we lived every day with purpose.”

Georgia bills to watch: Abortion pill access, transgender sports ban, parents bill of rights

Time spent with Dianna was especially precious to the girls. “She would always invite her friends and throw a nice dinner. Moments in the kitchen with her are most memorable, especially Thanksgiving,” Lucil says. “She would drive her special car to come see us. She did everything she could to be independent. She did not want to be at the mercy of anyone.”

In 2017, Chris’ health began to deteriorate significantly, and his mother wanted him home so she could care for him.

“Dianna has a will of iron,” Scott explains. “She felt that no one could take care of Chris like she could. So, after he celebrated Christmas with his family in 2017, she brought him home, and he died July 5, 2018.”

Op-ed: Would you like to save a life? Have a heart and learn CPR

“When Chris was sick, the care she gave him was wonderful,” Lucil adds. “It seemed a tragedy at the time – it is a tragedy to bury your child before you. But Dianna helped me see that death is just a transition to a new beginning. She raised a wonderful son, and I am so blessed to know him and to know her.”

Her own trials

Dianna began to experience her own symptoms while teaching second grade at White Bluff School, where she was in the classroom for 20 years. “She taught two full years in a wheelchair,” Scott says, “until she realized the fact that it is difficult to teach elementary school from a wheelchair.”

When Dianna retired, she continued to use her teaching skills, volunteering at Isle of Hope Elementary and at a special remote school set up at Isle of Hope United Methodist Church during the COVID-19 pandemic.

From pandemic to endemic?: Local doctor talks about where COVID-19 could be headed.

She also volunteered daily as a literacy/GED tutor at the St. Mary’s Center, and was so faithful to the task that they offered to give her part-time pay. She drove a specially equipped vehicle, and refused offers of assistance getting in and out of her car or with her wheelchair. Once, when her family couldn’t go with her on vacation, she went anyway, driving herself and visiting museums she had always wanted to see.

“She led a very active life. Nothing slowed her down. She was fiercely independent. She started working out three years ago with a personal trainer. ‘I’ve got to keep what I’ve got,’ she told me,” explains Scott.

In 2003, when the White Bluff staff filled out a get-to-know-you questionnaire, Dianna was asked if there was something (event, person, etc.) in your life of which you are VERY proud. She wrote “yes.” If so, what/who? “My son, Chris,” she wrote. The answer to the question, “Do you have a secret ambition?” “To be a world traveler.”

Coffee that's for the birds: Colombia's La Victoria Coffee Farm fuels cups and ecology

At the end, Dianna’s expressed wish to her friends was to be with her boys again.

“She will be rejoicing with her boys again, and they will all be standing, together," Scott says.

"That’s quite a picture.”

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: After losing sons to same disease, mother dies of hereditary illness