Dick Vitale made a promise to Jimmy V he won’t break, even as cancer tries to stop him

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

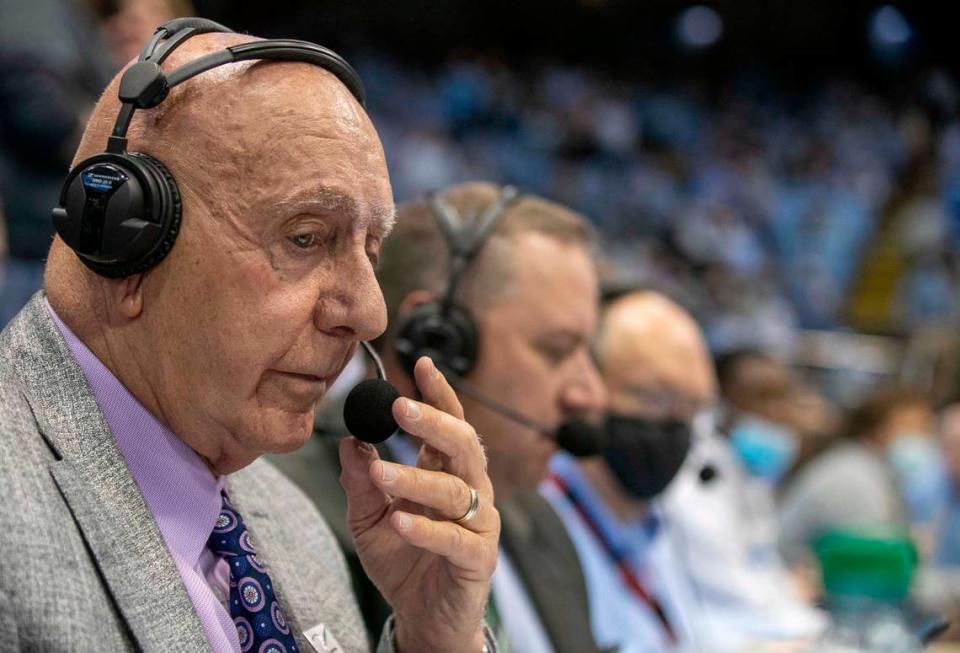

He arrived about three and a half hours before tip-off and walked slowly through a back hallway and into the Smith Center, a black leather bag in his left hand and his right free to offer a small wave or a fist bump or to grab onto the arm of someone he knew, his version of a hug. There are no strangers to Dick Vitale, only friends of varying degrees, and while his friends welcomed him back, his eyes widened and he smiled and at times he almost began to cry.

“Medicine,” he said quietly, and one of America’s most recognizable voices broke with hoarseness or emotion or both. “It’s like medicine to me. Getting to sit courtside is the best thing in the world. I did a game (last) Tuesday night, it was like heaven. It was my heaven. Hoops heaven.”

He had made this walk into the Smith Center, for a North Carolina game, too many times to count since it opened in 1986. Not even ESPN knew how many times he’d done it, here or anywhere, and Vitale couldn’t say, either. He has been with ESPN since its inception in 1979, one of the few who’ve been there since the beginning, and during those 42 years, he has called so many college basketball games, more than a thousand, that he didn’t know where he’d seen the most.

“No idea,” he’d written in a text message the night before, after he’d needed to take a break from talking. He could never talk for long these days about his diagnosis and treatment without thinking of the support he has received, the texts and the calls and all the rest, and thinking about that did make him cry, the gratitude turning into tears and muffling his words.

“It’s emotional,” he’d said over the phone, pausing to gather himself, “ ... how people ... have been so good to me. Really.”

He took a deep breath, sobs growing louder on the other end, his wife in the background telling him to get off the phone, to preserve his voice. He had to work. He had to rest. But now he had to cry and just 30 minutes earlier, Vitale said he’d been crying, too, at a message he’d received, and that he’d cried earlier that day after he’d talked with Pam Valvano, Jim Valvano’s widow and still a dear friend after all these years.

“It’s going to be a tough year for me,” he said, and in part he was talking about the chemotherapy sessions ahead but also he was talking about just making it through broadcasts without breaking down. Vitale, a man who’s long made his living with words, had no words to describe his gratitude.

“ ... Can I get off now?” he said, barely able to get the words out. “ ... I’m really getting all hoarse.”

And that was how the conversation turned to texting, Vitale considering how many times he’d been to Chapel Hill or Durham or Lexington; how many times he’d entered an arena and, by extension, millions of living rooms across the country; how many places where he’d uttered an “awesome, baby” or a “PTPer” and provided a soundtrack to some memorable basketball happening.

He didn’t know, only that “UNC and Duke RATE UP THERE,” he wrote, all capital letters, texting just like he calls a game — bursts of thoughts punctuated by enthusiasm. One moment he was answering a question and in the next he was sending a recent story someone had written about him and in the next he was sending information about his annual gala, benefiting the V Foundation, that has raised more than $40 million for pediatric cancer research.

“JUST SAW THIS,” he wrote with one link, followed by another about his fundraising.

“Sorry with all the stuff sent but raising $$ for kids so vital to me”

Then another message: A link to a story about his first game after his own cancer diagnosis.

“Great

Medicine,” he wrote, the words separated onto their own lines, and that was the phrase he used again Wednesday night when he walked into the Smith Center with his doctor by his side. There was a hitch in Vitale’s step, almost a small limp, and a light gray sportcoat hugged the curve of his back, shoulders drooping only a little after 82 years and countless late nights behind the microphone and, now, after his first rounds of chemotherapy.

He shuffled down the hallway, perking up when someone stopped him for a quick hello or a picture, and into UNC’s makeshift greenroom. There, snacks and coffee awaited, along with two large televisions on the wall, tuned to ESPN, and Vitale set his things down and asked for a hot tea with salt and began to make sure he had enough lozenges to last the night.

“Oh,” he said softly, almost grimacing, while he rubbed his neck. “I’ve got to keep my throat, man.”

That was not so much the cancer but the toll of age, the cost of doing what Vitale has done for so many years. It had been a long time since he could take his voice for granted, with the assurance that it would work the way he wanted it to work. Now he treated it like a finite commodity, as if he knew that one day the words and exclamation points would run out; that if he preserved his voice as much as possible now, God willing, he said, it would continue to keep him going.

Yet it was difficult, sitting still in silence. For so long, Vitale’s normal pregame routine included holding court with colleagues or visiting with coaches or making the rounds, meeting and greeting and hobnobbing. Being Dickie V, people called it. Being visible, being energetic, being a presence. But “this is not my normal pregame,” he said, sounding as if he missed it. “I just can’t do it.”

“I told Kirsch,” he said, referencing Steve Kirschner, UNC’s longtime basketball sports information director, that “I’ve got to save this.” Vitale gestured toward his lips and his throat.

“Two hours is a long time,” he said, and he settled into a chair and opened his briefcase and began reading over his notes, quietly, while he sipped his tea and saved his voice.

**

Not too long ago Vitale wondered if he’d be here, working. He wondered how long he’d be anywhere. He went in for a physical in September and said his doctor offered no shortage of praise, and that was after he received treatment for melanoma — skin cancer — in August.

“You’ve got the body of a 45-year-old man,” Vitale said, repeating words from his physician, and he recounted how his doctor went on about the strength of Vitale’s heart. “Because I work out, I don’t drink, don’t smoke.”

Vitale was “on cloud nine,” he said, and he and his wife, Lorraine, had just celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary. They’d taken the family to Hawaii, to the big island. Everyone was there. Vitale’s two daughters and their husbands. The five grandkids. A dream vacation with the people he loved, with his future certain. He’d work as long as he could and continue to raise money to help kids fight cancer and, most of all, he’d watch his grandkids grow up and start lives of their own.

And yet amid those dreams, there’d been signs. It began with the itching or maybe when he thought his skin looked a slight tint of yellow. When Vitale explained the warnings, he did not spare the details. It was as if he wanted people to know; as if he was thankful for not ignoring his body’s messages. It took time to unravel them, to understand why he scratched himself in his sleep until he bled; why his urine and stools were not the colors they were supposed to be.

Different tests kept coming back negative, weeks of tests, until a diagnosis: Bile duct cancer. A five-year survival rate lower than 10 percent. A death sentence, most likely, for an 82-year-old man, regardless of how healthy he might be otherwise.

“You start thinking about your family,” Vitale said. “You start thinking about your kids, your grandkids. And it was really a down time. I was very depressed, I was saddened.”

His doctors scheduled a surgery to remove the cancer, which in turn would have removed part of his liver. Vitale was fewer than 48 hours away from that surgery when his doctors in his hometown of Sarasota, Florida, finished studying his scans after he’d sought a second opinion. His bile duct was blocked, yes, and that caused the jaundice and other symptoms. But to them, it did not look like bile duct cancer.

It instead looked like lymphoma. He needed several more tests, and during one 12-day span, Vitale went under anesthesia six times while doctors poked and prodded their way inside his body to confirm his diagnosis. The second opinion proved correct.

Vitale went from a diagnosis that came with a 90% likelihood of death within five years to one with 90% odds that he’ll survive. He went from the eve of invasive surgery to cut something out of him to no surgery at all, and a treatment plan built upon six months of chemo.

“My wife cried, our daughters cried, I cried,” he said. “I mean, at my age, man ...” and his voice trailed off, silence filling in the blanks.

He felt now like life had become “almost a miracle,” He went public with his lymphoma diagnosis in mid-October and shared a video on Twitter on Oct. 20, two minutes of Vitale thanking the public for the endless messages of support; two minutes of Vitale describing how he planned on overcoming everything in front of him — all the chemo sessions and bloodwork and fear.

Thousands of well-wishes accumulated beneath his post, people sending digital hearts or “Love you Dickie V” or “Rooting for u Dickie V” or “You got this!” or “sending you infinite LOVE and prayers DickieV” and it was those words and all the others that helped give Vitale hope. His return to work, meanwhile, helped give him strength.

He received the approval last month, his doctors telling him, “leave the cancer and chemo to us and we will, when possible, approve you to go courtside.” Medicine, they told him. “We feel that would be great medicine for you,” to be back behind the microphone, the drama of a game offering a distraction from the drama of his cancer, two hours at a time.

“Dick’s 82, but he has the heart of a 30-year-old,” Dr. Richard Brown said Wednesday night, in a hallway around the corner from where Vitale prepared to call UNC’s victory against Michigan. “And we don’t tend to treat people by their time clock age” but by their health.

“He’s actually in very, very good shape,” Brown said. “And he’s highly motivated, which always helps, and he wants to do everything he can to get well. So those are all good ingredients. ... We still have a ways to go, but we’re trying to figure out ways of getting treatments in and allowing Dick to be Dick in terms of the things he loves to do. And we want him to do.”

Brown doesn’t usually travel with Vitale but Wednesday night was different. Brown pulled out a Michigan hat he’d been hiding, and whispered that he was a Wolverines fan. He’d flown up to North Carolina with Vitale and a few others on a private jet, and had taken Vitale up on the offer to see him work and take in a game inside one of college basketball’s hallowed venues.

Just then, Vitale came from around the corner, looking for more lozenges.

“You got any more?” he asked.

One of the employees in the Smith Center, helping Vitale with his needs, appeared and pulled out some Halls.

“Lemon and honey,” she said.

“That’s good,” Brown said. “Give him a whole bunch of those.”

Vitale held out his hand, accepting a palmful that lasted him the night.

“He’s a Michigan guy,” he yelled out, blowing his doctor’s cover, before going back for some more reading. Tipoff was still more than two hours away.

**

Sometime after 6:30 Wednesday night, Vitale received a reminder from someone at ESPN: Be sure you’re watching at 7 o’clock, sharp. For 15 years now the network has celebrated what it calls “V Week,” when it recognizes the legacy of Valvano, who led N.C. State to that improbable national championship in 1983, and his creation, in his final act, of the V Foundation.

Valvano announced its founding on March 4, 1993. It’d been a decade then since the miracle of ‘83. Valvano was dying of a particularly aggressive form of cancer. Everyone remembers the speech he gave that night at the ESPYs, the ESPN awards show where Valvano received the Arthur Ashe Award for courage. The network replays his speech every year around this time.

Vitale knew the speech was going to be played Wednesday night. What he didn’t know was that before and after it there’d be a tribute to him and his own cancer fight. A few minutes before 7 he settled into a chair and turned up the volume and soon the program started, one of Vitale’s colleagues back at ESPN headquarters in Bristol, Connecticut, introducing the segment.

“Coming up next you can hear that iconic speech, as well as a tribute to our friend and colleague, Dick Vitale, as he continues to be an inspiration in his battle against cancer.”

“Oooh, boy,” Vitale said.

An image popped up on the screen, Vitale in a hospital with part of his medical team.

“That’s me getting chemo,” he said. “I’ve not seen this.”

A montage began rolling, a recent clip of Vitale repeating his signature phrase — “awesome, baby” — fading into an “awesome, baby” from a long time ago, his voice younger and smoother but in many ways the same then and now. Suddenly Vitale had some hair again, and fewer wrinkles, and on the screen it could have been the late-1970s or maybe the early-80s, and the Vitale up there, on the TV, was holding a stick microphone while his partner said, “welcome to the ESPN network,” while the Vitale here, the 82-year-old man in the greenroom, watched alone.

One after another, moments from his broadcasting career appeared on screen, brief scenes fading into each other, like a dream. There was the Jerry Stackhouse reverse dunk at Duke, followed by Jeff Capel’s heave near midcourt — Vitale punctuating both — and then there was Vitale courtside somewhere in one moment or describing a buzzer-beater or a dunk the next.

“So much fun I’ve had over the years,” he said, almost in a whisper, while another moment transformed into the next.

“Ohhh, great game,” he said, a single play igniting a more complete memory.

“I can’t believe the fun I’ve had,” he said to no one in particular while in the background the younger version of himself yelled into the microphone.

Soon the music turned more somber and it was 1993 again, Vitale on one side of Valvano, helping him up the stairs at the ESPYs, and Mike Krzyzewski on the other. And the Vitale in the greenroom looked at the Vitale on television, a ring of dark hair still holding onto his head in those days while he stood up on stage, off to the side.

“Mike Krzyzewski and I, to this day, we talk about it,” Vitale said now. “I can’t believe how he gave that speech. Because we had seen him the day before. It was brutal.

“See, the reason I stand there, I thought he was just going to accept the award. I’m like in awe that he’s standing there, speaking.”

Vitale grew silent again and it was like he had gone back in time. Only now he mouthed some of Valvano’s words, the bit about crashing into the locker room door at Rutgers while giving the Lombardi speech; the part about taking time every day to laugh and to think and to cry; the way Valvano implored his audience then and now, almost 30 years after his death, to pursue their goals and to live with a purpose.

“I still have so many goals,” Vitale said now, when his old friend arrived at that part of his speech. “I want to see my grandkids all graduate,” and his youngest was in 10th grade, six or seven years from finishing college. Vitale planned to be there.

On TV, Valvano was talking about how cancer could take away his physical abilities “but it cannot touch my mind, it cannot touch my heart, it cannot touch my soul.”

“And those three things are going to carry on forever,” Valvano said then.

“And those three things are going to carry on forever,” Vitale said now, at the same time.

The next day, more than 28 years ago, Vitale called Valvano when he was back at home to check in. Valvano did not want to come to the phone, Vitale said. He told Pam to put him on and eventually a weary, fatigued Valvano came on the line.

“It’s over, Dick,” he said, according to Vitale. “I’m done.”

No, Vitale said, the old basketball coach coming out of him. “Come on, man” — you’ve got to keep fighting. Valvano, his voice faint, told him he knew the end was near. He told Vitale to raise money for research, to keep alive Valvano’s dying wish. It was their final conversation. A month later, Valvano was gone. Now it’s Vitale, almost three decades later, persevering.

After the Valvano speech came another montage: Sick kids — or ones who were sick — appearing and thanking Vitale for his work to raise money. Last year, his gala raised more than $6 million. Next May, he’s hoping the gala will surpass the $50 million mark, overall. As Vitale watched the children on screen Wednesday night he could name them or tell their stories.

“Brain cancer,” he said at the sight of one.

“He died right after,” he said at the sight of another.

“These kids all have cancer,” he said, his eyes watering.

Moments later it was over. Kimberly Belton, an ESPN producer who has worked with Vitale for a long time, walked into the room.

“You OK?” Belton asked.

“It was powerful,” Vitale said, and he didn’t feel a need to say more.

Soon enough it was game time and Vitale walked out of the tunnel and took his seat at mid-court, where he’s called so many UNC games over the years. Who knows how many more there’d be? The pregame music stopped for a moment and the public address announcer recognized Vitale, thousands in the crowd rising from their seats to applaud his appearance. The game began, and UNC won easily. From the other side of the building, Vitale could be seen if not heard, his hands flying around to articulate a point, his body moving with excitement at a key moment or big play.

Undoubtedly, some of the viewers at home groaned when Vitale went off script, as he often does. And, undoubtedly, some of those viewers questioned how and why Vitale keeps going, perhaps not realizing or appreciating that Vitale remains one of the last threads connecting the college basketball of today to the game it once was, back when he often called Dean Smith “the Michelangelo of college basketball” and gushed over Dante Calabria’s full head of hair.

“As long as I can do it,” he said of being courtside, and now it was not just a professional passion but medicine, too.

When it was over Wednesday night, he lingered at the broadcast table for a while and walked off the court as slowly as he entered the building. He made his way through the tunnel, stopped for a picture or two, stopped to talk to people who approached and then handed his security escort a wad of cash before walking out the door. He’d rest Thursday and Friday was another day of chemo and then soon enough he’d be back in an arena, somewhere, for a different kind of medicine.