How Dickens did it: 'A Christmas Carol' debuted 180 years ago, and won hearts instantly

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

NEW YORK — To hear Philip Palmer, the literary curator at the Morgan Library & Museum tell it, the story behind the writing of "A Christmas Carol" sounds, well, like something out of Charles Dickens.

It is October 1843 and Dickens’ debts are mounting. The 31-year-old author has moved his growing family into a new home in London, a bigger house with more servants. His father and his brothers keep taking out loans using his famous name. He is forced to take out ads in newspapers warning creditors not to loan his father any more money.

By 1843, Dickens was already known for “The Pickwick Papers," “Oliver Twist,” “Nicholas Nickleby,” and “The Old Curiosity Shop.” But his latest work, “The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit,” serialized in magazines, isn’t the barn-burner he’d hoped.

He devises what he calls “a little scheme” to right his financial ship and earn him what he hopes will be £1,000. He’ll write a ghost story for Christmas. But he’ll have to work fast. It’s nearly Halloween. He cancels social engagements, instead seeking inspiration on long nighttime walks through London. Walking by night, writing by day, the novella emerges.

In just six weeks, Dickens crafts the story of Ebenezer Scrooge, a “covetous old sinner” who is visited on Christmas Eve by the ghost of his seven-years-dead partner Jacob Marley.

Tormented and chained in the afterlife by the errors of his worldly business ways, Marley secures a chance to help Scrooge escape the same fate: He’s to be visited by the ghosts of Christmas Past, Christmas Present and Christmas Yet to Come. The spirits show Scrooge where he turned away from humanity and the common good. He stifles his “Bah! Humbug!” reflex and vows “to honor Christmas in my heart, and try to keep it all the year.”

"A Christmas Carol" was published 180 years ago this year, on Dec. 19, 1843, and sold all 6,000 copies of its initial printing in five days, Palmer says. It introduced the world to Scrooge, his faithful clerk Bob Cratchit and his crippled boy, Tiny Tim, to Scrooge's boyhood employer, Fezziwig, and Scrooge's nephew, Fred. And Marley.

It is a Christmas fixture, with productions and readings seemingly everywhere, from Jupiter, Florida, to Louisville, from New York to California and all stops in between. Audiences arrive knowing the first line ("Marley was dead, to begin with") and the last ("God bless Us, Every One"). They know every plot twist, every ghost. Some know every line, and when an adaptation has altered it from the original. Its hold remains.

But why?

Tony-winning actor Jefferson Mays, whose one-man adaptation was a critic's pick on Broadway last December, is sure that the first time he heard it — read by his parents — inspired him to be an actor.

Actor Paul Carlin, who wrote an adaptation and played Scrooge at the Maltz Jupiter Theatre in Florida this month, calls Dickens' work a sort of "backdoor brilliance" that sneaks up on its audience.

Elliott Forrest, an award-winning producer and director whose radio-play adaptation was a gift for New York Public Radio's audience more than a decade ago, brought that version to the stage in Louisville this month, accompanied by the Louisville Orchestra.

Forrest counsels his casts — which have included Scrooges as varied as David Hyde Pierce, F. Murray Abraham and Kathleen Turner — to never forget the three H's of "A Christmas Carol": heart, humor and horror.

An it's-not-too-late story, 180 years old this year

It’s a redemption story, an it’s-not-too-late story, a story that has been told and retold in more than 100 film adaptations and countless stage productions, radio dramas and staged readings. It has been assayed by Muppets and Mr. Magoo. Theaters have been kept afloat with the guaranteed audiences "A Christmas Carol" promises, just as that other holiday chestnut, "The Nutcracker," permits ballet companies to see another summer.

Last Christmas, Mays played 50 characters, from Scrooge down to a potato bubbling against a pot lid, in his one-man "A Christmas Carol" on Broadway, an adaptation he wrote with his wife, Susan Lyons, and director Michael Arden.

In an interview alongside Lyons from their California home, he expressed awe for what Dickens achieved in those six weeks more than seven generations ago.

"It truly is magical. It has to be the most adapted piece of literature in the history of literature," Mays says. "But it's so many different kinds of stories wrapped up into one. I think that's one of the sources of its appeal. It's a fantastic phantasmagorical ghost story. It's a sort of moral Cinderella story of transformation and redemption. It's a novella about a whopping midlife crisis. It's a cracking good yarn that has had this universal appeal."

The story is suited to the stage, Mays says, because that's how Dickens wrote it.

"His daughter, Mamie, would sit in his study sometimes to watch him in the act of writing," Mays says. "She described him leaping up from his desk, running to a full-length mirror and gesticulating wildly, speaking in all sorts of different funny voices, assuming different shapes, and then rush back to his desk and sit down and put it on paper. He was very much an actor. This is why it's so often adapted for the theater, because it is so theatrical."

Mays says he loves reading it aloud to an audience, as Dickens did on tours of the U.K. and America.

"It was the first of his works that he ever performed in front of an audience and it was the last of his works that he performed just a few months before his death in 1870," Mays says. "He loved that feeling, that contact with a live audience."

Those nighttime walks, Lyons says, gives the narrative its mood.

"That mystery that nighttime brings, that sort of haze. Walking past your history, walking past the house you grew up in, or the house where your father got arrested and all sorts of shadows that he brings into the story."

Mays' connection to the story goes back to his childhood home in Connecticut, when his parents read it aloud to him.

"I'll never forget that evening in the 1970s, my father's somewhat detached, lilting narrative voice. And then my mother, who would completely be possessed by every character she read. She was Marley's Ghost, she was little Fan, she was Belle, she was Scrooge, she was the Ghost of Christmas present, she was Bob Cratchit.

"To see this woman that I thought I knew so well transformed before my eyes into these completely other characters scared me to death and compelled me," Mays says, captivated by the long-ago memory. "I think it's what made me want to be an actor. I said, 'I want to do that, too.' But I never forget that moment. We read it every year, part of my personal history. It is my story. And I think people have that magical relationship with this."

'Tour de force' language; how Dickens worked

Dickens on the page is different than Dickens on the stage, Palmer says. Reading "A Christmas Carol" provides a direct connection to "the power of Dickens' language and the power of those little details and the warmth that they create."

There's this line, describing Scrooge's home:

"He lived in chambers which had once belonged to his deceased partner. They were a gloomy suite of rooms, in a lowering pile of building up a yard, where it had so little business to be, that one could scarcely help fancying it must have run there when it was a young house, playing at hide-and-seek with other houses, and have forgotten the way out again."

"I think the language is just a tour de force," Palmer says. "This is a book that repays rereading more than so many others."

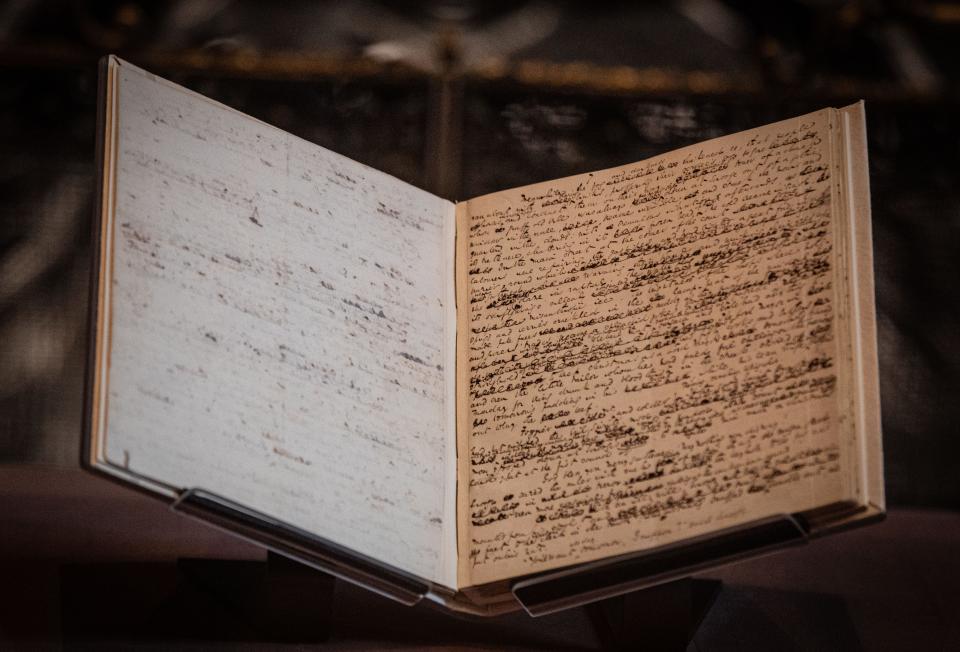

He should know. The Morgan displays Dickens' original manuscript each holiday season, giving visitors a priceless glimpse into the way the debt-ridden writer toiled that feverish fall.

Perusing the open manuscript, visitors can see him writing and correcting, using his goose quill to cross out sections and change words to make the setting more evocative, to punch up the prose. Palmer notes that Dickens rarely altered the dialogue in the manuscript, but finessed the lines that set up the scenes.

What you see when looking at the manuscript — or at the Morgan's book "A Christmas Carol: The Original Manuscript Edition," which presents the original page on the left and a typeset version on the right — is the writer at work.

"There are no other notes or documents that tell us how he wrote this book, in part because he wrote it so fast, he didn't have time to take notes and write out the manuscript once and then copy it somewhere else," Palmer says. "It's all here and that's, I think, a really exciting aspect of this manuscript. The whole archive is just there in front of you on the page."

'A sledgehammer blow,' a lie that tells the truth

The Morgan displays the bound hand-written manuscript — which was presented to Dickens' friend and creditor Thomas Mitton in early December 1843, after the first edition was at the printer's — in a glass cube near the imposing fireplace in the imposing study of J. Pierpont Morgan, a room that is built to intimidate.

(It's not lost on Palmer that the novella ended up with Morgan, one of the world's most famous bankers, who bought it before 1900.)

But the simple novella has a power all its own, one whose message prompted some American bosses to give their workers Christmas Day off years before it became a federal holiday in 1870.

"It has a lighthearted feel to it that immediately makes us think of Christmas and puts a smile on our faces, but it also has this real serious side to it," Palmer says. "Charles Dickens saw it as a sledgehammer blow, as something that could actually do more than maybe legislation or political pamphlets or nonfiction writing, but rather a fable, a lie that can tell the truth even more poignantly than the truth itself. Dickens saw that in the book. And I think we still see that in the book today."

At the Morgan, to give visitors a new peek into Dickens' process, the staff turns a new page in the manuscript every year, just as Scrooge turns over a new leaf every 25th of December.

Palmer says the duality of the story is what has made “A Christmas Carol” as popular as ever. Like the solstice time in which it arrives, it has more dark than light, more cold than warmth, but light and warmth win out in the end.

3 delightful edits

The nightly jaunts through London fueled Dickens, Palmer says.

"This is one of the ways he learned London and I think one of the reasons why you get such a feeling for the city and its people and its atmosphere in his books," he says. "I can almost imagine him walking and then maybe walking again another night and getting another idea."

There were changes along the way, some of which are in the manuscript, some of which were made when Dickens looked over the printer's proofs. Palmer shares three, which will delight "Carol" fans:

"One of my favorite revisions, from the manuscript to the printed book is Tiny Tim. His name is Tiny Fred initially in the manuscript. So that changes. We already have, of course, Fred the nephew, and you can't have two Freds in the story, so that change makes sense.

"'Bah! Humbug!' was, at one point, 'Merry Christmas! Humbug!' Bah was kind of added later. He crossed out 'Merry Christmas' and put in 'Bah' above.

"The famous line at the end when Dickens says, 'And Tiny Tim, who did NOT die' was something that is not in the manuscript at all. Dickens seems to have forgotten about Tiny Tim at the end of the book when he was writing it by hand. He added that line somewhere between the manuscript and the printed version. So in the proofs, which don't survive, he clearly added it there."

Why ‘A Christmas Carol’ works

Carlin says the genius of Dickens' text is how accessible it is but how its message demands attention. He put it in actors' terms, invoking two wildly different playwrights, a popular just-for-laughs American and a society-challenging German.

"He's like Neil Simon connected with (Bertolt) Brecht," Carlin says, laughing. "It's like, how do you do that?"

Elliott Forrest, known to New York Public Radio audiences as a host on WQXR classical station, says Dickens goes deep.

"He was about 30 years or so ahead of Freud and the idea that there is redemption in revisiting childhood traumas, which is what those ghosts do, they take him back to a romantic breakup," Forrest says. "He's not mad at Fred because he's just a Grinch. He's mad at Fred because Scrooge's only sister died at childbirth and he still blames his nephew for that. There's all this trauma that Scrooge revisits and has real redemption, has a real breakthrough.

"I think there's something inherent in that, that we can all change, that we can be better people, that we can learn from what either we put ourselves through or what other people put us through," he says.

The story, Forrest says, comes together when Scrooge articulates that transformation: “I will live in the Past, the Present and the Future. The Spirits of all three shall strive within me.”

180 Christmases, and counting

For 180 Christmases, the story's spell has been as predictable as the power of those Spirits to convert an old miser. But every year offers a new audience discovering the story for the first time.

Forrest recalls seeing a child in audience in the Mellwood Art Center in Louisville this month for whom the story was a first-time revelation.

"They were so surprised at the transformation, like this guy was really mean and awful for an hour and now he couldn't be happier or more giving," Forrest says. "Try to remember before you really knew the whole story. I love that there are still people who might not know where this is going."

Mays, a year removed from his Broadway one-man "Carol," itches to play the miser (and that potato) again.

"I'm not done. I want to do it for the rest of my life in some form and fashion. It's part of me and I want to do it forever."

For his part, Dickens sought to relive that heady best-seller Christmas of 1843, publishing a Christmas book every year for the next five years.

“None of them were ever as good as 'A Christmas Carol,' but they all made a ton of money," Palmer says. "They made more money than 'A Christmas Carol,' because by that point, everyone wanted the latest Charles Dickens Christmas book.”

See ‘A Christmas Carol’ manuscript

What: Charles Dickens’ original handwritten manuscript of "A Christmas Carol" from December 1843

Where: The Morgan Library & Museum, 225 Madison Ave., New York

Through: Jan. 7.

Hours: 10:30 a.m. to 5 p.m.,Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays, Saturdays, and Sundays; 10:30 a.m. to 7 p.m., Fridays. Closes at 4 p.m., Christmas Eve and 5 p.m. New Year's Eve. Closed Mondays, Christmas Day, New Year's Day.

Tickets: $22; $14 seniors (65 and over); $13 students (with current ID); free for those 12 and younger, accompanied by an adult. Entry to the museum is by timed ticket. Advance timed tickets are suggested for best availability, but not required.

Call: 212-685-0008

Web: https://www.themorgan.org/visit

This article originally appeared on Rockland/Westchester Journal News: NYC's Morgan Library turns page on original 'Christmas Carol' text