How did Afghanistan end this way? The finger-pointing begins.

WASHINGTON – The blame game in Washington intensified Tuesday as critics – including leaders in Congress – pounced on claims by embattled Biden administration officials that they had no clue a blitzing Taliban would take Afghanistan so quickly and without a fight.

President Joe Biden himself has sought to spin the spiraling crisis as one that was inevitable, largely out of his control and a development that took the White House by surprise.

“This did unfold more quickly than we had anticipated," he said in a televised address Monday. "The Afghan military collapsed, sometimes without trying to fight.”

But a wide variety of experts, including some current and former U.S. intelligence and military officials, counter that the White House had ample warnings of just such an impending catastrophe.

They say an intensive inquiry is needed to find out who knew what and when about the probability of the crisis now engulfing Kabul, and why Washington appeared to be blindsided by such a swift and total collapse of the Afghan government and security forces.

“This is a policy failure. It was a rushed withdrawal against the advice of the intelligence community and the U.S. military," said Marc Polymeropoulos, who spent 26 years in the CIA, including significant time on the ground in Afghanistan. "Ultimately, we're much less safe now as a result."

One senior staff member on the Senate Intelligence Committee, which oversees the nation's spies and analysts, confirmed that the U.S.-gathered intelligence flowing in from Afghanistan was dire.

"There are plenty of questions being raised about what went wrong, and a lot of finger-pointing about who screwed up and whether the intelligence was correct and if it went to the right people," said the senior committee staff member, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive committee matters. "Because if it did, obviously this was more of a policy failure than an intelligence failure."

More: 'Nobody should be surprised': Why Afghan security forces crumbled so quickly to the Taliban

The raft of questions now go far beyond why the Biden administration had to beat such a hasty retreat that it stranded – some say betrayed – legions of loyal Afghan military and civilian allies now at the mercy of Taliban militants. There is also the question of how America could leave behind so many potentially sensitive classified documents and expensive, deadly weapons – including Black Hawk helicopters, Humvees and possibly shoulder-fired missiles.

National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan said the U.S. doesn't have a "complete picture" of how much defense materials was lost but conceded that a fair amount of equipment – including Black Hawk helicopters – was seized by the insurgents.

Sullivan said the president was presented with a choice of fulfilling former Afghan President Ashraf Ghani's plea for additional air capability and other equipment with the hope that they use it to fend off the Taliban, or deny the request over the risk that it would fall into the Taliban's hands.

"Both of those options had risks. He had to choose, and he made a choice," Sullivan said.

And then there is another big question looming over the latest round of recriminations: Did the CIA and Pentagon simply miss many months worth of apparent efforts by the Taliban to buy off and win over Afghan civilian and military leaders in what was essentially a bloodless coup? Or did the Biden administration and Congress choose to ignore that intelligence, as well as the clear signs that the Afghan military could not possibly defend its own capital?

“The idea that President Biden, with four decades of experience and multiple trips to Afghanistan, somehow has faith in the Afghan army is ludicrous,” said Polymeropoulos, who retired from the CIA Senior Intelligence Service in 2019.

Instead of trying to throw U.S. intelligence agencies “under the bus,” Polymeropoulos said, Biden should shoulder the blame for failing to anticipate how easily the Taliban could co-opt Afghan military and police forces that were demoralized, underpaid and facing a future in which they could side with the insurgents or risk being killed by them.

Former Acting CIA Director Mike Morell defended his colleagues Tuesday on Fox News.

"The intelligence community for the last 20 years has been more pessimistic than any other organization in the U.S. government about how this was going and whether victory was possible. So to blame intelligence now infuriates me, absolutely infuriates me," he said.

And on Wednesday, the CIA’s former Counterterrorism Chief for South and Southwest Asia came forward to say that Biden’s claim of being taken by surprise was “misleading at best. The CIA anticipated it as a possible scenario.”

Before his 2019 retirement, Douglas London wrote in a Just Security blog post, he was responsible for assessments concerning Afghanistan prepared for former President Donald Trump. He said he later advised Biden on the same issues as a volunteer with his Presidential campaign’s counterterrorism working group.

“The decision Trump made, and Biden ratified, to rapidly withdraw U.S. forces came despite warnings projecting the outcome we’re now witnessing,” London wrote, describing recent events as "Not An Intelligence Failure — Something Much Worse."

Whether those CIA warnings were specific enough to be acted upon will be a central focus of the upcoming Congressional investigations, according to the Senate staffer and other sources.

More: A timeline of the US withdrawal and Taliban recapture of Afghanistan

Calls to investigate

The Senate Intelligence Committee already is combing through all of the intelligence gathered in and about Afghanistan, the Senate staffer confirmed, and is working with Democrats and Republicans on the Foreign Relations and Armed Services committees to coordinate a series of planned investigative hearings into actions taken by the White House, Pentagon, State Department and intelligence agencies.

"We owe those answers to the American people and to all those who served and sacrificed so much," said Sen. Mark Warner, D-Va., the chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee.

In its defense, the Biden administration circulated a long list of talking points on Capitol Hill claiming that the administration knew that there was "a distinct possibility" that Kabul would fall to the Taliban. But the White House memo stressed: “It was not an inevitability. It was a possibility.”

Some current and former U.S. national security officials contend there were no such illusions about whether Afghan troops could withstand pressure from the Taliban without U.S. support. They cited U.S. military intelligence assessments from June that concluded that the Taliban could overrun government forces within 90 days, or as soon as 30 days.

More: 'I am begging you guys:' Florida veteran fights to bring his Afghan interpreter to the U.S.

"This was a political failure. The intelligence community got this right,” Rep. Mike McCaul of Texas, top Republican on the House Foreign Affairs committee, told MSNBC. “I got the briefings. I can't go into detail. But they predicted, within six months, then three months. Actually, the Taliban worked even faster."

When asked about those military intelligence reports, Biden said last week that he was not considering any change of plans even though the Taliban had already taken at least seven provincial capitals in a span of several days with little or no fighting.

Meanwhile, the CIA also was developing similarly stark intelligence and sharing it up the chain of command, sources said.

“We have noted the troubling trendlines in Afghanistan for some time, with the Taliban at its strongest militarily since 2001,” one senior U.S. intelligence official told USA TODAY. “Strategically, a rapid Taliban takeover was always a possibility. … We have always been clear-eyed that this was possible, and tactical conditions on the ground can often evolve quickly.”

In its 2021 Annual Threat Assessment Report in April, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence said that the Afghan government “continues to face setbacks on the battlefield, and the Taliban is confident it can achieve military victory.” It also concluded that Kabul “would struggle to hold the Taliban at bay if the coalition withdraws support,” but it offered no details in the public version of the classified report.

The brain trust – and what must be weighed

As congressional investigations ramp up into what went wrong in the final days of America's deployment in Afghanistan, one key focus will be on the quality and specificity of the intelligence provided by the CIA and military intelligence agencies – and what was done with that information by the National Security Council and other Biden administration policymakers.

That will train a spotlight on the National Security Council, the White House’s brain trust that is tasked with assessing the many – and often conflicting – streams of intelligence and making recommendations on what the best policy options might be.

That's easier said than done, especially when intelligence assessments from the field often paint a rosier picture of what's happening on the ground – for instance, the capabilities of the Afghan army it trained and equipped – than similar assessments by analysts in Washington, D.C., who are less institutionally invested in such things, said Javed Ali, a senior National Security Council official in the Trump administration.

The NSC held 36 deputy and principal level meetings on Afghanistan between April 13 and last weekend that focused on “over-the-horizon counterterrorism planning, special immigrant visas applicants and embassy security," according to a senior administration official who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss the meetings. Eight of those meetings centered on humanitarian scenario planning.

Earlier this month, the White House convened a tabletop exercise on evacuation scenarios “to pressure test every element of our planning through August 31," the scheduled deadline to withdraw all U.S. troops, the official said.

It was clear by last spring, based on media reporting, that top military leaders like Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin and Gen. Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, were warning of the implications of the kind of rapid withdrawal Biden was planning so he could meet a deadline negotiated by the Trump administration, Ali said.

“I would have to believe that ... somewhere along the way people proposed some interim option – like a small counterterrorism or special operations presence on the ground that aligns with our vital national security interests,” said Ali, who also spent 16 years in top national security positions at the Defense Intelligence Agency, Department of Homeland Security and FBI.

“To me, it seems really surprising that we weren't even willing to do that. Now was that a policy decision? Or was it operational or political?” Ali asked. “Those are all really important questions.”

On Tuesday, Pentagon spokesman John Kirby evaded the question of whether Biden overruled military leaders in his decision to withdraw U.S. troops.

"The commander in chief is the commander in chief," Kirby said on ABC's "Good Morning America." "It’s not about overruling his military leaders or his other advisers. He is given options, he is given the pros and cons for each option, and then it is up to the commander in chief to decide. He was advised by the Defense Department. We have a seat at the table. We provided our advice and counsel. The president made his decision, and now we’re in execution mode. That’s the way it works.”

Long predicted

For many years, most U.S. spies and soldiers working the Afghanistan account have assumed that today's worst-case scenario was not only possible but likely.

That’s not the fault of rank-and-file U.S.-trained Afghan forces, who have fought heroically and sustained heavy casualties even in the face of massive government corruption and wavering political and financial support from Washington.

“But all the institutional stuff – the poor morale, corruption, poor leadership, poor accountability, no pay – that was a problem 15 years ago when I was an adviser” in Afghanistan and it never got fixed, said Mike Jason, who retired in 2019 as a U.S. Army colonel after 24 years commanding combat units in Afghanistan, Iraq, Germany, Kosovo and Kuwait.

The subject of how long Afghan forces could fend off the Taliban came up repeatedly during U.S. military meetings, including two Jason attended in 2007 and 2001, he said. Each time, the consensus was that the Afghan army would fall immediately after the withdrawal of U.S. forces – if not sooner.

“So now, lo and behold, the army collapses. Well, no kidding,” Jason said. “When the (U.S. aid) money started drying up and the Taliban comes in with better paychecks and we are telegraphing internationally that we're out of here, at some point you’ve got to make a calculation for yourself and the safety of your family.”

Ali pointed to these questions as an intelligence failure – the apparent inability of successive U.S. administrations to understand the transactional nature of Afghan culture. It's how the Taliban was able to take over Afghanistan so quickly without using much force, he said.

“That’s just the way Afghanistan works," Ali said. "This all goes back to our fundamental misunderstanding of Afghanistan as a country and how it operates. The tribes there are rooted in ethnicity and tribal and clan affiliation. And those kinds of connections, I think, led to those deal arrangements that were happening very quickly and on the ground. And the U.S. never had really good insight on that.”

Biden's 'buck stops here'

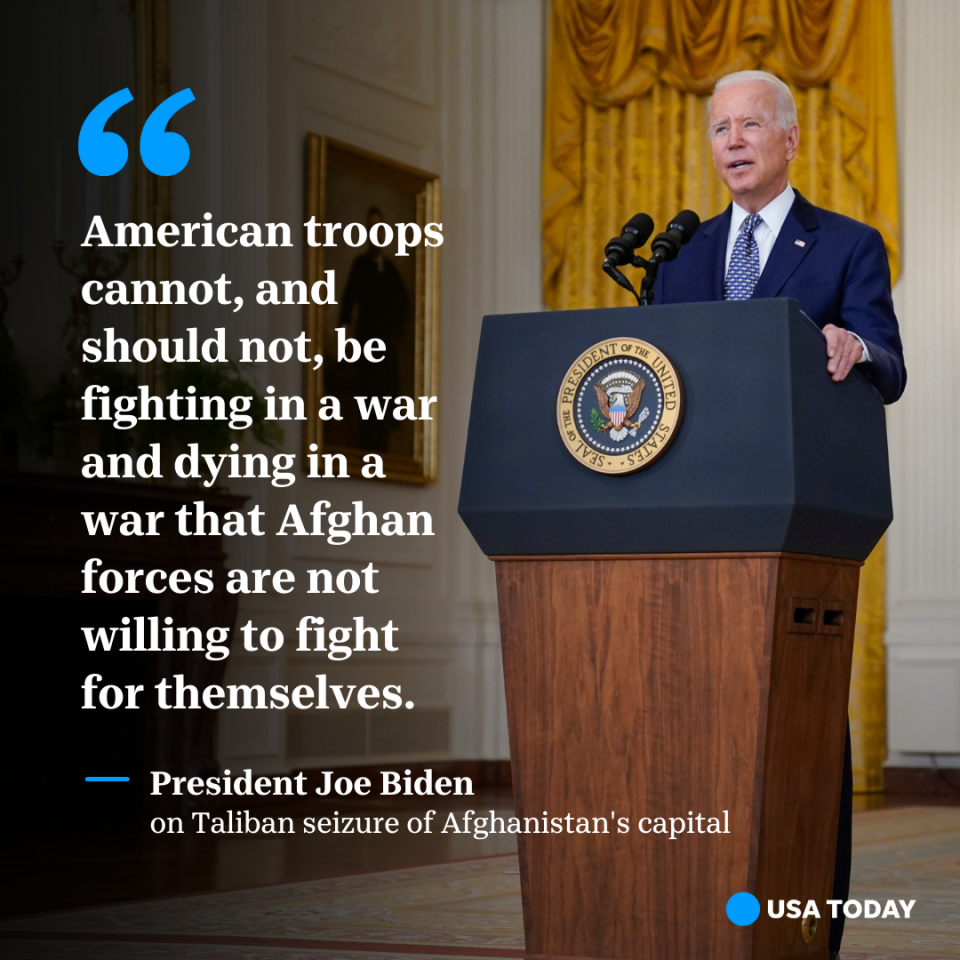

Faced with mounting criticism, Biden returned briefly Monday from Camp David, the Maryland presidential retreat, to deliver a defiant speech in which he declared he stood “squarely behind my decision” and blamed Afghanistan political leaders who “gave up and fled the country.”

The rapid U.S. withdrawal was necessary to end America’s longest war, Biden said, and Ghani had personally promised in June that his U.S.-trained military could – and would – fight to protect the country from a hostile Taliban takeover. “And obviously,” Biden said, “he was wrong."

More: What President Joe Biden said in his address on Afghanistan

But the president focused much of his defense on the strategic decision to leave, one that majority of Americans support, and avoided addressing criticism over the tactics used to evacuate the embassy and the execution of the withdrawal.

He acknowledged the harrowing images of Afghans clinging to U.S. military aircraft and the scramble to evacuate the American embassy, scenes that evoked the U.S. retreat from Saigon at the end of the Vietnam War, and described the withdrawal process as "hard and messy – and yes, far from perfect."

Administration officials echoed Biden’s defense, arguing that they had planned for every contingency, including one in which the Taliban swiftly overran the capital and the U.S. needed to close its embassy. Officials pointed to the 6,000 troops that were deployed to Afghanistan to assist with the evacuation.

One senior administration official, who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss the matter, noted that Taliban fighters had been gaining ground, especially in rural territories, before Biden took office.

The Taliban has been building a significant military operation since they struck a deal with former President Donald Trump in February 2020, the official said, which was a key factor in the president’s decision-making in the spring.

When the president met Ghani at the White House in July, according to the official, Biden asked him to lead efforts to unite Afghan political factions, display a show of unity in which he brought together political factions in support of his government, and adopt a military strategy that consolidated Afghan security forces and geographic areas where they had the best chance of fighting off the Taliban.

"None of those things happened," the official said.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: As Taliban takes control in Afghanistan, is Biden responsible?