Did the Columbus scrapyard explosion threaten public health, environment? Here’s what we know

On the evening of Sept. 17, a smoldering pile of debris at a scrap metal recycling yard in Columbus inexplicably exploded.

The powerful blast at Radius Recycling shook houses throughout the historic downtown district, giving the impression that “something landed on my house,” a resident at 2nd Avenue and 7th Street told the L-E. Radius Recycling, which recently rebranded from Schnitzer Steel, is in an industrial corridor at 10th Avenue and 5th Street.

The ensuing fire blazed orange flames and thick black smoke within the confines of the scrap yard for several hours. Not too long after Columbus Fire arrived, the battalion chief called for the fire to be “blanketed and smothered” with a fire suppression foam, requesting assistance from Fort Moore and Columbus Airport vehicles equipped to use an Aqueous Film Forming Foam (AFFF).

The fire smoldered for several days. No one was injured and the origins of the explosion are still under investigation.

Local officials and public health experts fail to agree about the potential health risks from the fire and the use of AFFF to suppress it for Columbus residents, firefighters on the scene, and Radius Recycling employees. First responders weren’t able to test the air quality at the time, and the nearest air quality measuring station was 7 miles away.

Why foam?

The AFFF was necessary to suppress the fire, according to Columbus Fire Marshal John Schull.

“Water is more of a cooling agent which doesn’t have as good of a capability to blanket the fire,” he said.

The Columbus airport (CSG) vehicle and Fort Moore’s vehicle applied a combined 550 gallons of AFFF foam on the fire (The white foam covered the grounds at Radius Recycling, which can be seen from this drone footage).

Fort Moore used 330 gallons of AFFF.

The CSG airport used 210 gallons of Chemguard 3%, a Tyco Fire product. This specific brand is one of several in a slew of lawsuits between firefighters and AFFF companies for health issues, including cancer, allegedly connected to the foam.

The foam contains high levels of poly-fluoroalkyl chemicals (“PFAS”), colloquially known as forever chemicals — which are toxic and known to cause cancer. PFAS-AFFF is banned in 12 states, but not Georgia.

It is also being phased out by the Department of Defense. The National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) requires the DOD stop purchasing PFAS-based firefighting foams by Oct. 1, and stop using them completely by Oct. 1, 2024.

“Our department doesn’t use AFFF because of its environmental concerns,” Fire Captain Jerome Rayford of Station 6 in Columbus said.

That’s why the fire department had to call in support from the airport and Fort Moore. Since 2019, Georgia fire departments have only been allowed to use the foam in emergency situations.

Public health concerns

Emory University environmental health professor Amina Salamova said PFAS don’t degrade in the environment.

“They tend to get into people’s bodies and accumulate there. They don’t excrete or metabolize,” she said. “Whether or not PFAS get in the air is undetermined as it is a big group of chemicals and some mixtures are proprietary so it’s hard to get [exact ingredients].”

Given the new NDAA requirement and other litigious issues with AFFF, airport fire chief Jerome Turner Jr. said the FAA recently released a list of vendors and specs for transitioning away from AFFF to fluoride-free foam (F3).

“It has been previously used in military installations but has not become available,” Turner said. “We are currently in contact with vendors now on the acquisition and cost transfer to upgrade to the F3 agent for use during the event of an aircraft emergency.”

Using foam in city fires isn’t common: it usually is needed for suppressing large jet fires.

“This type of foam is typically used for combating class B fire’s (flammable liquids, like gasoline oil, and certain chemicals),” Turner said in an email.

Schull suggested this was a class D fire, meaning it was metals like magnesium, titanium and sodium that caught fire.

“This was a large, large class D combustible metals fire,” Schull said.

The day after the fire, Columbus Water Works examined the scene to determine whether there could be any seepage of AFFF into soil or water affecting sewer or sanitary systems.

“The inspection confirmed that none of the foam left the site,” Vic Burchfield, senior VP for Columbus Water Works, told the L-E. “None of the water that was used left the site.”

The black smoke was toxic to those that may have breathed it in. However, Rayford believes there is nothing for locals to worry about as far as air quality.

“No one should feel like they were in danger from toxic smoke unless they were close to the area,” he said.

Four firefighters were wearing breathing apparatuses while fighting the fire.

“These were the guys in the danger range,” Rayford said.

Despite the fire being more generally contained after a few hours, Samalova suggests the consistent burning for a few days is concerning.

“There could be metal particles that went into the air,” she said. “Air quality should be a concern here especially in areas close to the facility. It’s best to avoid those areas for some time.”

Testing the air

Columbus Fire is equipped with monitoring devices to help determine how toxic the air is, but Firefighters weren’t able to test the air while fighting the blaze.

“We didn’t get a chance to use our monitoring device because we were trying to keep everyone in a safe range,” Rayford said. “There was so much going on that night. Once the air leaves the area, it dissipates. No one should feel like they were in danger, as far as air quality.”

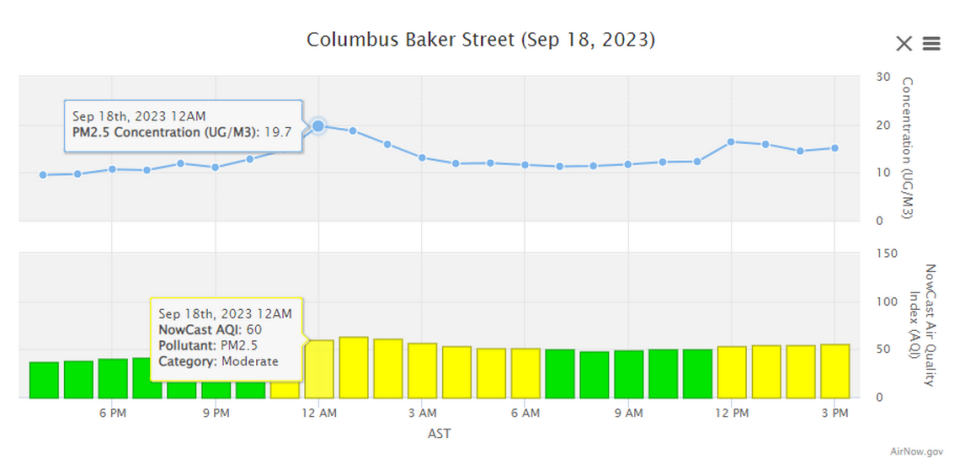

There are two air quality monitoring stations in Columbus: One at CSG and another about 7 miles south of the fire on Baker Street. According to the device on Baker Street, the Particulate Matter 2.5 (PM2.5) concentration was detected at about 19.7 around midnight the night of the fire. The PM2.5 is matter smaller than a strain of hair and can get into lungs.

“The healthy and safe level country-wide is is 12 PM 2.5,” Rob Gore of ADEM said. “If a private citizen wants to get their own monitor you could use Purple Air, but they aren’t scientifically calibrated to be used for regulatory agencies.”

Two days after the fire, embers still smoked as fire crews were “separating the condensed fire scraps,” Schull said.

On Sept. 19, two employees were working to signal any trucks or vehicles (including L-E media) to not enter the premises. Scrap metal trucks were signaled to turn around and not enter.

All 30 of Radius Recycling employees were told to return to work the morning of Sept. 21.

What is scrap metal?

What does Radius Recycling permit on their premises? Mainly iron and steel at the Columbus location, but other metals including aluminum, copper, and brass and other ferrous and non-ferrous metals can be dropped off and sold at Radius.

Georgia has the most Radius Recycling locations anywhere in the U.S. but Radius Recycling has 54 metal yards located throughout the country.

Just last month the company underwent serious scrutiny in Oakland for a metal scrap yard fire, for its environmental violations. The cause of that fire is still under investigation.

Radius Recycling requires all suppliers “of automobiles, appliances and other light iron products destined for shredding to sign a Hazardous Materials Compliance Contract,” Eric Potashner, Radius Recycling spokesperson told the L-E via email. “Our team conducts visual inspections of all incoming loads to our facilities. Generally speaking the material is industrial scrap which can come from individuals or companies.”

With different types of metals and their ancillary products entering the waste stream, lithium batteries from electric vehicles and smartphones have caused several metal scrap yard fires throughout North America, including one two weeks ago in Saint John’s waterfront.

Richard Meier in Palmetto, Florida is an explosion investigation expert. While Meier isn’t working the Columbus fire, he suggested the explosion wasn’t simply a lithium-ion battery, since it shook houses miles away. It’s possible, he said, that a battery ignited something else.

“Not everything is pure metal, aluminum, steel, copper, brass, sometimes other materials are attached,” Meier’s said. “If you get a large explosion there is something in the scrap stream that is not supposed to be there.”

Schull, the fire marshal, says the explosion’s origin is still being investigated. Radius Recycling is doing its own investigation, he said, and took samples to help determine the origin.

Video footage from Radius Recycling shows the small debris that smoldered then exploded.

“Our comprehensive surveillance system with multiple video cameras are monitored ‘round the clock by Radius’ Control Center,” Potashner said. “It was this internal team that notified the Columbus Fire Department.”

Meiers suggests there needs to be more screening of recycling materials coming in.

“This will cost money and take more time and…more people,” he said.