They did DNA tests to verify they were sisters. By accident, they found their birth father.

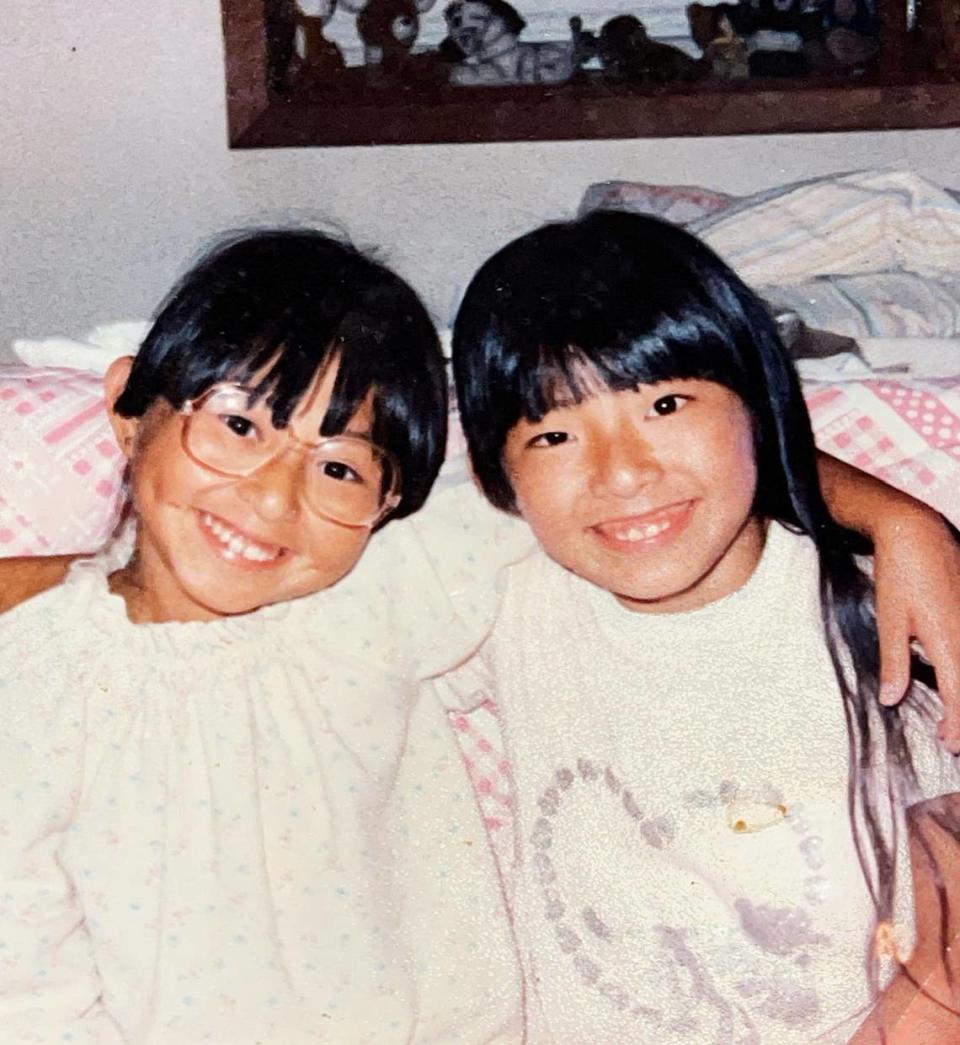

Other than the fact that they both are clearly Asian, Becca Webster and Dee Iraca don’t look alike.

Not that all twins are identical, of course. But they share almost zero physical features, and also have personalities that are vastly different.

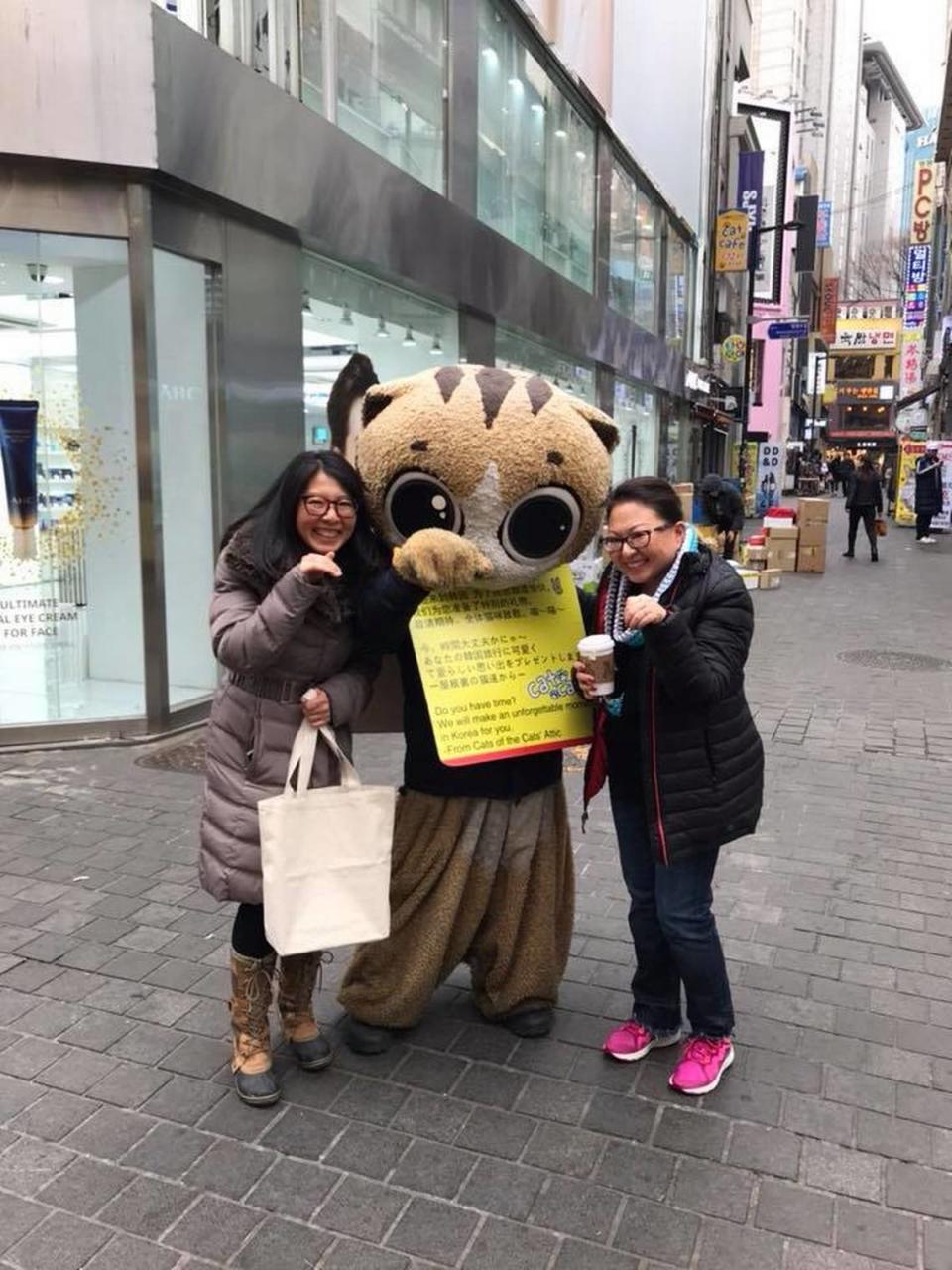

So after returning to South Korea for the first time since they were adopted — in 2018, when Dee, then a Denver, Colorado-based chef, was tapped to cook for the USA Olympic Alpine Ski Team at the Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang — and after a visit to the agency they were adopted through in 1973 raised more questions than answers, the two women who had been told all their lives that they were twins agreed:

We need to finally get a DNA test.

That spring, Dee, who now lives in Davidson, and Becca, a Concord resident who works as a nanny, dropped saliva samples into the mail.

Becca and Dee have an elaborate and amusing story about how simple user error caused them to spend three days believing their 23andMe tests had determined they were in fact not related — before realizing they had failed to click on the link that would show them their matches.

But in the end, it was finally settled, after almost 45 years. They were, indeed, fraternal twin sisters.

Besides each other, though, the test yielded no other results of note, and the law of diminishing returns applied to the every-few-months email digest Dee and Becca got from 23andMe with new sets of matches. They only ever produced cousins several times removed.

Not that the sisters were looking, or hoping, for anything in particular. It was just the novelty — which eventually wore off.

Then one afternoon in August 2021, more than three years after they’d done the tests, Becca opened her email to find a message someone had sent to her through 23andMe’s system ... from a woman claiming to represent her birth father.

She immediately called Dee, who had an identical message. They both noticed they had a new match: “Father.” The username was “Mr. P.”

“Wwhhhh — whaaaaat?” Becca remembers thinking. “I was just in shock.”

A few minutes later, the phone started ringing.

A shot in the dark for both her, and him

Rebecca Kimmel also was adopted from Korea as a baby, a few years after Becca and Dee.

For her entire life, Rebecca had believed the backstory her adoption agency originally provided about the way she became an orphan: that she was abandoned by her birth parents.

But in 2018 — while preparing to return to the country of her birth for the first time as part of a “homeland tour” for Korean adoptees — Rebecca obtained information from her adoption agency in Seoul that conflicted with what she’d been told about where and how she was found.

From there, she went down a serious rabbit hole.

After her tour, Rebecca continued to pore over her adoption records and dug into stories about the child-export boom driven by the Korean dictators of the 1970s and ’80s. She soon joined a growing group of adoptees convinced that agencies had switched their identities to replace children who died, became ill, or were reclaimed by birth parents before they could be shipped to the West.

Eventually, her research led her to information that she says suggested she was a twin. That discovery led her in 2020 to a post on Korea Adoption Services’ family search bulletin board, which aims to reconnect adoptees searching for their birth families.

The man who’d authored the post was looking for his long-lost twin daughters, who he’d not seen since the day they were born. He seemed fuzzy about when exactly that day was, even fuzzy about the year in fact.

Rebecca felt like she had to chase the lead, though. She just had a gut feeling about it.

Strong enough that she contacted one of the largest television networks in Korea to pitch the idea of making a documentary centered around her return to the country to track down this man, based on the possibility he might be her birth father. The Seoul Broadcasting System agreed, and with a film crew in tow, Rebecca successfully located him — Park Jong Gyun — living alone in a tiny home on the South Korean island of Jeju.

There, he told Rebecca that he and his wife, who had three sons already, were persuaded by hospital staff to give up their twin daughters on the day they were born — and then he and Rebecca took a DNA test to find out if this was a genuine reunion.

They both hoped it was. But with the cameras rolling, Rebecca and “Mr. Park” appeared numb upon learning it was not.

She returned to the U.S. deflated. Before she got on the plane, however, she suggested to Mr. Park and his middle son, Young-bu, that they take a genetic test that would share results into a vast database. After all: Why not? Rebecca bought a pair of 23andMe test kits, created accounts for them that she agreed to monitor, and collected their saliva samples. Back home, she mailed them out to be processed.

Three weeks later, on Aug. 12, 2021, the results came in. Rebecca jumped up and down on her bed when she saw them, screaming excited screams.

“I was like, Oh, s---,” recalls Rebecca, who lived in Chicago at the time but has since relocated to Washington state. “This is real.”

She sent individual messages through 23andMe to both of the women who had matched as Mr. Park’s daughter. She impatiently monitored the inbox until she saw one of them had read it. She impatiently waited for a response. In the meantime, because one of the women had a username that looked like a real name and also had listed her home state, Rebecca — who in the past three years had gotten very good at internet-sleuthing — found a cellphone number.

The first time, she was sent to voicemail. It was hard to know what to say, so she just said something along the lines of this: “My name is Rebecca. I somehow met your birth father in Korea. Please call me.”

She waited, impatiently again, then not long after, tried the number, again.

This time, the woman — Becca Webster, who had taken the DNA test three years earlier mainly just to see if Dee Iraca was really her sister by blood — picked up her phone.

‘Nope. I’m good. My life is just fine.’

Becca and Dee were adopted at 4 months old by a couple who were happy to grow their family by two in one fell swoop.

The girls grew up in a predominantly white area of Pennsylvania and although they looked different from all of their friends, they always basically felt like they were white.

They didn’t eat Korean food, didn’t learn the Korean language, didn’t dream about visiting Korea, never spent time wondering about their birth parents. They both went to the same mostly white college. Both married white men. And for most of their adulthood, both pretty much felt the same way:

A birth-family search had scant appeal.

Dee does recall one time in maybe the late ’90s, maybe the early ’00s — pre-internet boom, in any case — contemplating initiating a birth-family search with a newspaper ad. “But it would have to be there (in Korea), and we’d have to get a translator,” she said. “And when I started thinking down that road, I was like, That is way too much work. There was such a small chance that we would find somebody. Then you start thinking of all the weird people that come out of the woodwork that say that they’re related to you, and they’re really not.

“It just kind of scared me, and I was like, Nope. I’m good. My life is just fine.”

Dee’s trip to Pyeongchang for the Olympics in 2018 shifted things, though. Becca showed up in Korea as a surprise, and had reached out to their adoption agency, Holt, in the hopes of maybe getting new information about their adoption.

And “Holt gave us the exact same file that we’ve had our whole life,” Dee says. They came away, however, fixated on some old information on one of the documents. “At the very bottom it says at 7-something a.m., we were ‘found.’ It doesn’t say that we were dropped off by somebody; it says we were ‘found’ in front of this hospital.

“So we started thinking, if we were ‘found’ together, well, it doesn’t mean that we were dropped off together.”

Back home in the Charlotte area, they got online and placed their orders for one 23andMe DNA test each.

Hard to believe what was happening

Becca was struggling to process what Rebecca was telling her over the phone.

“Before we got into it too much,” says Becca, recalling her initial conversation with this strange woman, who quite clearly could hardly contain her excitement. “She’s like, ‘I know you have a lot of questions. It’s a lot of information. Let’s do a Zoom call with your sister.’ So we set it up for within the next hour.”

It’s true: Becca did have a lot of questions. For instance, How did this woman get her phone number? What was this woman doing with an account that appeared to belong to a man calling himself “Mr. P”? Are we somehow being played here??

“It was so unbelievable,” Becca says, that she actually called 23andMe just to see if they could tell her if this was a scam.

“I was like, ‘Hi, so I just received some information and it says that I matched to a father, but what’s the likelihood? I mean, how certain does this work?’ And as I’m saying it, I’m like, This guy probably thinks I am such an idiot. ... He’s like, ‘No, it’s pretty accurate,’” she recalls, laughing. “But I don’t know, as stupid as that sounded, I felt like I had to make sure 23andMe exists, and that this was really happening.”

Becca describes her and Dee’s initial Zoom call with Rebecca as “a tornado of information.”

It took days for her explanation and her revelations to sink in. Then the following week, just as the sisters were starting to get their bearings back, they were in surreal territory again — on a Zoom call with Mr. Park, their birth father.

Through a translator, Mr. Park told Becca and Dee a story that flew in the face of the one that was on their adoption records, which simply stated they’d been found abandoned on a sidewalk. The truth, he said, was that his pregnant wife was sick. That she’d had an emergency C-section. That one of the twins was born weak and in need of special care. That his mother and his wife’s mother were summoned to the hospital to help them make a decision, and that there was basically a mutual agreement to give them up for adoption due to the couple’s financial hardships.

But whereas this was a reunion Mr. Park had dreamed of for years, and while this is exactly the type of outcome Rebecca had hoped for for herself, what’s it like to suddenly be told at 48 years old, “Hey, your birth father — who you’ve never met, who you imagined was probably dead, who you weren’t looking for, at all — is alive. He lives on the other side of the world. He doesn’t speak your language.

“Want to go spend a couple of weeks with him and a bunch of other family members you never knew existed?”

‘It’s like meeting a stranger’

Rebecca was incredibly eager to get them to Korea. Mr. Park was, too.

From a logistical standpoint, however, it was a significant challenge for the sisters. A ton of time off from work. Several thousands of dollars just for the plane tickets for Dee and her husband, Sean, and for Becca and her husband, Chris. Figuring out arrangements for Becca’s teenage son. And reconciling all of this with other travel plans and travel expenses and time away from work.

Dee, Becca and their husbands finally boarded a plane bound for Seoul this past October, almost exactly 14 months after the phone call from Rebecca that changed their lives — and roughly 5-1/2 years after taking that 23andMe DNA test.

The moment Mr. Park embraced his twin daughters for the first time since their births in 1973 is depicted touchingly on-screen, by the Korean documentary filmmakers who continued to follow Rebecca’s story and expanded it to include Becca and Dee. (The film, “Rebecca in Wonderland,” was broadcast by SBS Korea in December.)

Still, that moment was as complicated, emotionally, as you might expect.

For one, the presence of that film crew made the situation feel somewhat unnatural and chaotic, and made Becca and Dee somewhat self-conscious and guarded. Also: “It sounds a little harsh when I say this,” Dee admits, “but even if we might have talked on the phone a couple times, or we wrote a letter, or Zoomed ...

“It’s like meeting a stranger.”

But while so much of the next two weeks was filled with strangeness, and with complicated emotions, it was also filled with unexpected and simple pleasures.

A traditional Korean feast of kimchi, japchae and seaweed soup prepared by Mr. Park in his home. A party held in their honor and attended by a variety of aunts and uncles and cousins and other relatives, at which they were formally and warmly welcomed into the family, applauded, served a lavish seven-course meal. The donning of hanbok dresses that Mr. Park had made for them as gifts. A visit from Rebecca — who shares an equally special relationship with Mr. Park not just because she made all of this happen for him, but also because they both know what it feels like to spend years searching for answers; for a loved one.

On top of all that, whereas Becca and Dee’s adoption agency could tell them nothing about their birth parents’ circumstances in 2018, Mr. Park told them everything.

How it was some kind of parasite that had stricken their mother and put her in the hospital and necessitated the emergency C-section. How a hospital representative told him it would cost this much to pay for her treatment and the procedure, and how he rushed off to borrow the money from a relative but couldn’t find them. How, after being talked into relinquishing the babies to an adoption agency, he and his wife never received a bill from the hospital.

How, about 10 years after they were born, he and his wife returned to the agency hoping it would reconnect them with their twin girls but were told it didn’t have any information.

How their birth mother died in her 50s.

How in 2018, right around the time his daughters were making their first visit to Korea, he started aggressively appealing to government bodies and adoption agencies to help him find his long-lost twins.

When Dee and Becca hugged him at the airport before leaving to return to Charlotte, Mr. Park no longer felt like a stranger.

Does this story have a happy ending?

Rebecca, for her part, is happy to have played a role in Mr. Park’s life story. At the same time, his story devastates her whenever she thinks too much about it.

“I mean, can you imagine going to the hospital — taking your mother who’s sick — and them being like, ‘Oh, you can’t pay the hospital bill, so we’re just gonna take your mother, and you’re just never gonna know what happened to her.’ That’s insane, right? But that’s basically what was happening” in Korea back in the ’70s, she says. Basically what happened to Mr. Park.

“I just feel like it should be a more balanced narrative,” Rebecca continues. “The Mr. Park story is not a beautiful story.

“It’s a lucky story, in the end. But it’s not a beautiful story. He suffered a lot. And it’s not like now that he’s met his twins, everything in his life is great. He’s 83. How many more times is he gonna see them?”

In addition to inspiring the documentary, Rebecca has promoted awareness of falsified adoption papers and origin stories, and has given guidance and feedback to Korean adoptees interested in birth-family searches.

Becca and Dee, meanwhile, are still adjusting to their new normal.

From a practical standpoint, communicating with Mr. Park isn’t easy. For one, they self-translate their messages to him into Korean and do the conversion of his replies into English without assistance, too. They frequently are unsure about the quality of their translation skills. Korea also is 13 hours ahead of Charlotte, so for most of the day, either they’re awake when he’s asleep, or vice-versa.

As for Rebecca’s question about how many more opportunities Mr. Park and his daughters will have to see each other? Although the sisters say, of course, they would love to go back — and Becca really wants to take her adult son next time — they face the same challenges as before. Time and money chief among them.

“We’re trying,” Dee says, “to figure out what having a relationship moving forward looks like. Because we want to have a relationship, and we’re happy to know now, and know more about our story, and the truth, and all of it. It’s just ... it’s a lot, you know?”

But whether you consider this story to have a happy ending because it reunited a father with his daughters, or whether you consider that reunion to be overshadowed by the sad fact that Mr. Park has had this gaping hole in his heart for so long, consider this:

Dee and Becca, who as girls and even as women basically felt like they were white, no longer feel this way.

‘Opening ourselves up, wanting to know more’

They never cared about Korean food before; in May, to celebrate turning 50, they dined at a Korean restaurant. They never cared about the Korean language; now, they’re exposed to it in some fashion on an almost-daily basis. They never dreamed about visiting Korea; now, despite the significant obstacles, they figure there will be a number of ’round-the-world flights in their future.

To see Mr. Park while they still can, but even after he’s gone — to see their many other relatives. To see more of the country of their births.

“It’d be remiss to say this experience didn’t change us,” Becca says. “I mean, we have now more of the truth of where we come from, and we’re opening ourselves up to the Korean culture and wanting to know more. It’s just more of an acceptance. Because we’ve been raised in America, to always be, like, ‘No, we’re Americans! We’re just like white people!,’ ... and now saying, ‘But we’re not.’

“Yeah,” Dee says. “We are Korean.”

“We’re Korean,” Becca continues. “We were born in Korea. We have the maturity now to feel more proud about that. And now, to have this fall upon us — to have our answers, to have the truth — is profound.”

Becca looks at Dee and Dee looks back at Becca and even though it’s been coming up on two years since that blindside of a phone call from Rebecca, the sense of shock that emanates from their auras still feels fresh.

“We could have never guessed this could have happened to us,” Becca says, finally.

“But then it did.”