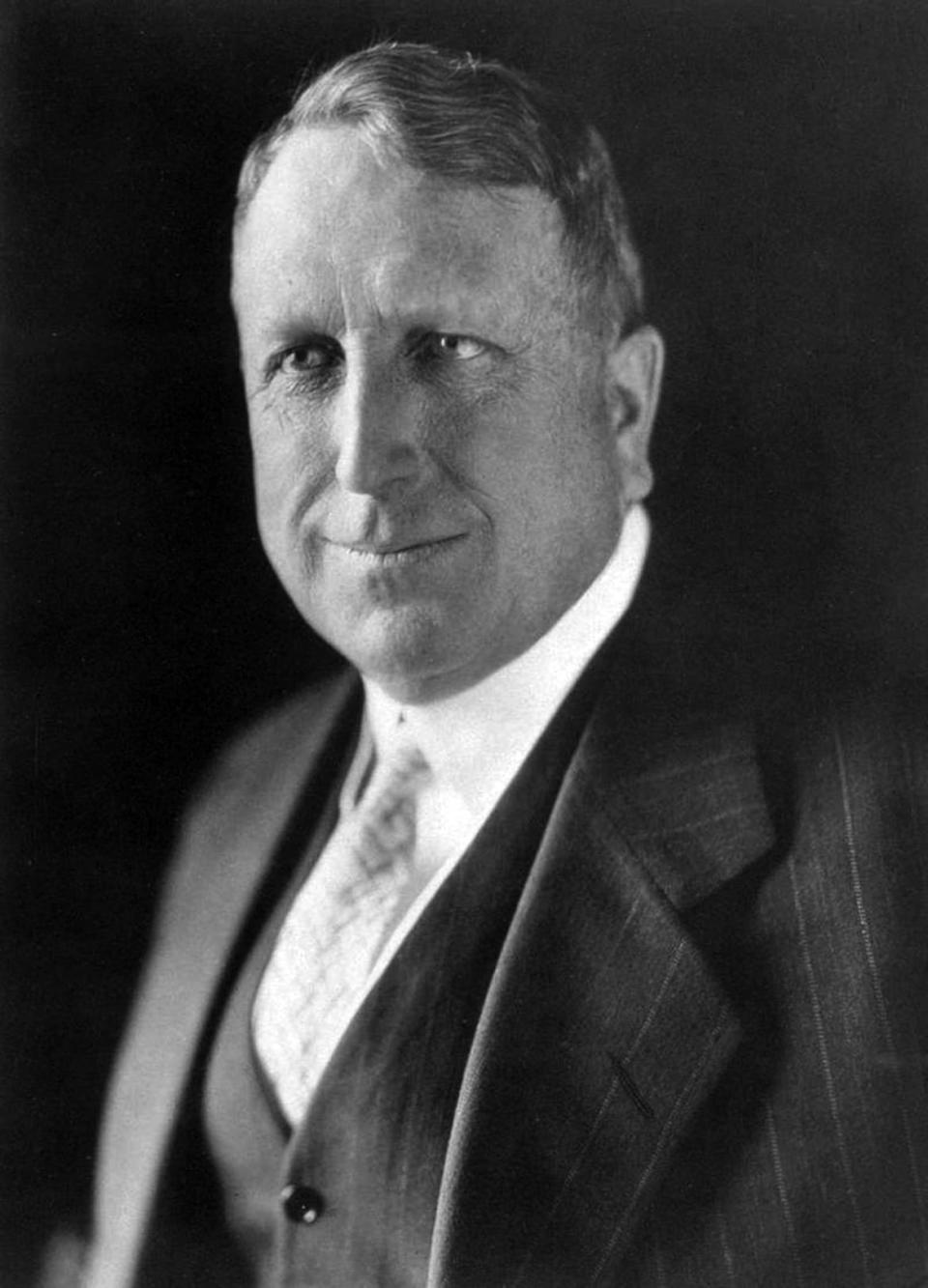

How Did ‘the Father of the Western’ Die on William Randolph Hearst’s Yacht?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

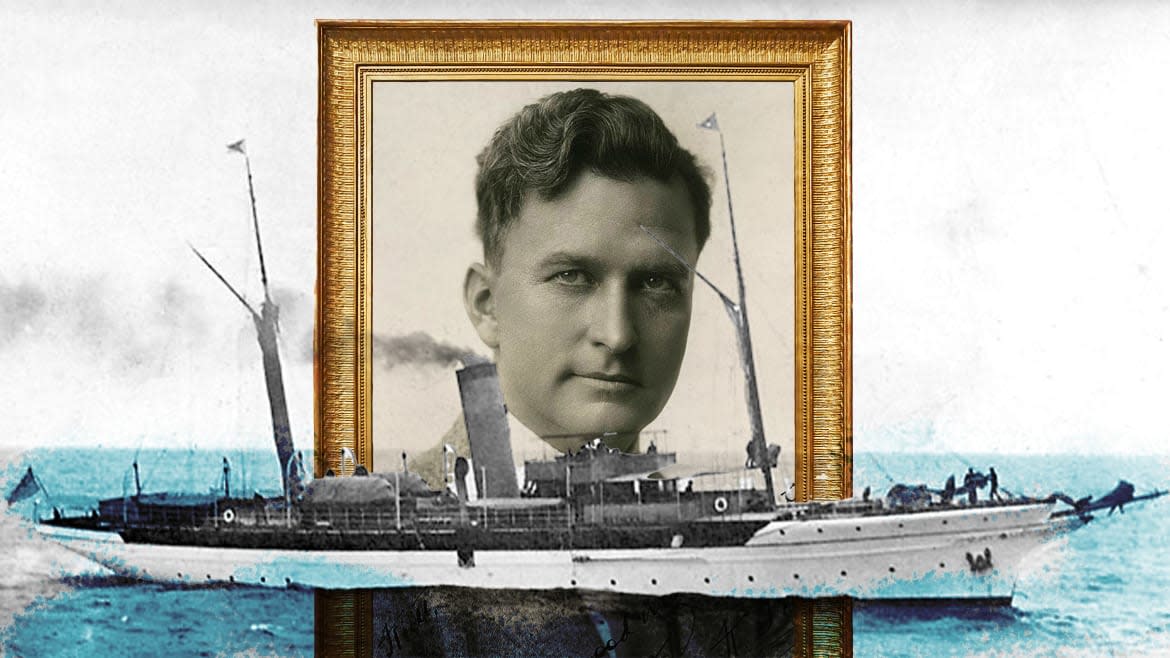

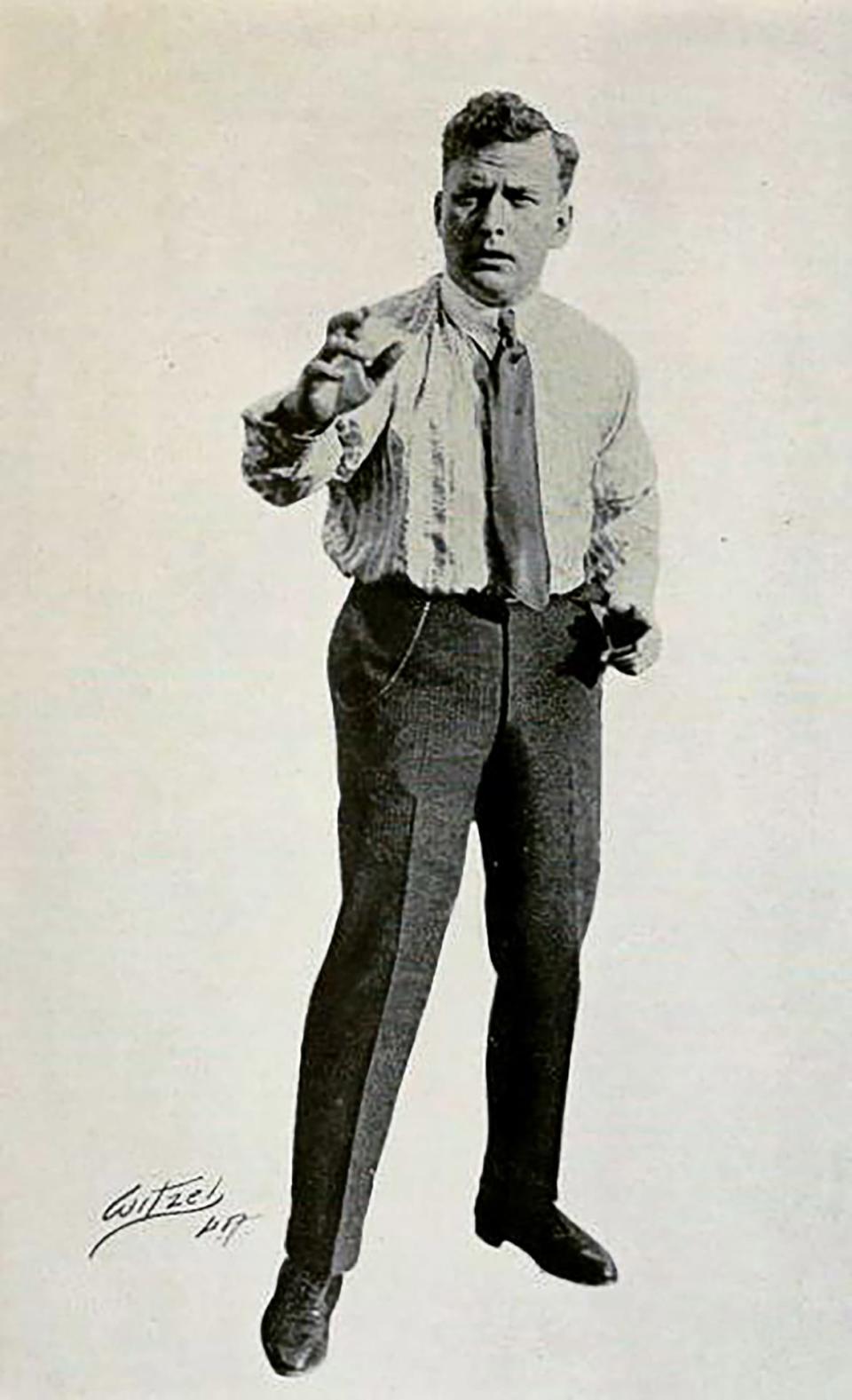

Famed silent film producer Thomas Ince, known as the “Father of the Western,” loved boating. It was a cherished hobby that he incorporated into several of the more than 100 movies he made. In his obituary, The New York Times even reported that he once ran away from home to sign onto a ship’s crew. Luckily his parents stopped him—they thought acting was a more solid career choice for the boy.

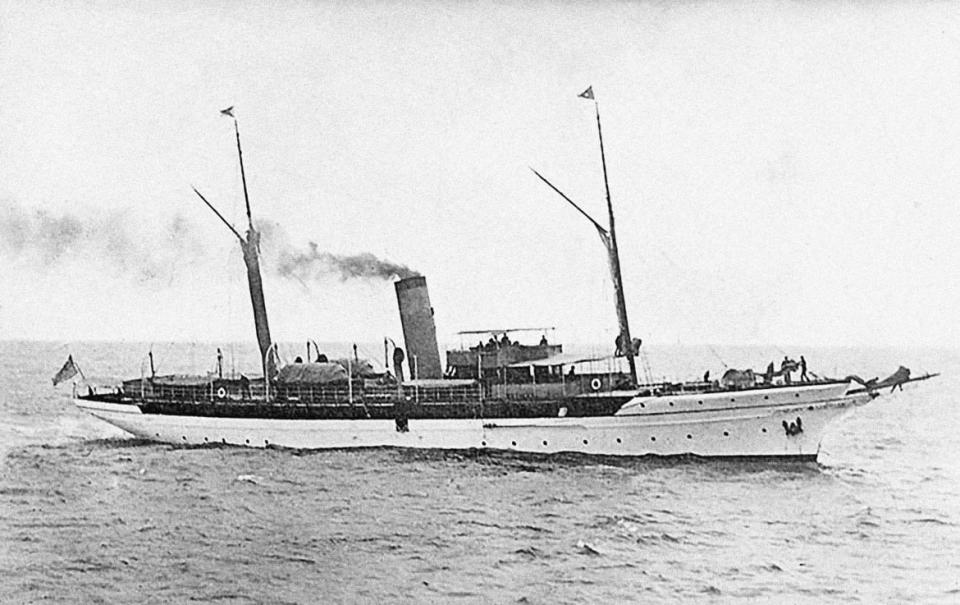

Needless to say, when the celebrated newspaperman and member of the American aristocracy William Randolph Hearst invited him on a jaunt on his yacht Oneida in November of 1924, it must have seemed like the perfect way to celebrate his 44th birthday. An A-list group of Hollywood machers and stars enjoying only the best food and Prohibition-be-damned drinks on a fancy 200-foot-long sailboat off the coast of California? What could go wrong?

California’s Most Famous House Was a Battle With Owner’s Shopping Addiction

That trip would come to overshadow the filmmaker’s legacy and tarnish those on the boat with the lingering stain of scandal. After one day at sea, Ince was quickly evacuated back to shore. He died shortly after. While his cause of death was by all accounts accurately reported—heart troubles—the actions of those left behind could fill a manual on how to accidentally create a fake scandal that will tarnish your reputation. Since that day, rumors have swirled suggesting that, rather than dying after a night of overindulgence, Ince was murdered.

Ince had only just entered middle-age when he boarded the Oneida that November, but by all accounts he was not in the peak of health. Given his rapid rise to success in the film industry—“achieved only through the stubborn fighting qualities which characterized the man,” according to The New York Times—it is fair to speculate he might have been a bit of a workaholic, which manifested in stomach ulcers and angina.

Born in 1882 to a Rhode Island family involved in the theater, Ince made his stage debut at the age of 6, got his first serious theater gig at 15 and, aside from that minor detour when he dreamed of becoming a sailor (surely the only time parents have begged their child to be more responsible and become an actor), he didn’t stop.

From an early age, Ince laid the groundwork for a career beyond acting. He started his own company in his early twenties and, when stage work was hard to come by, began to look to Hollywood.

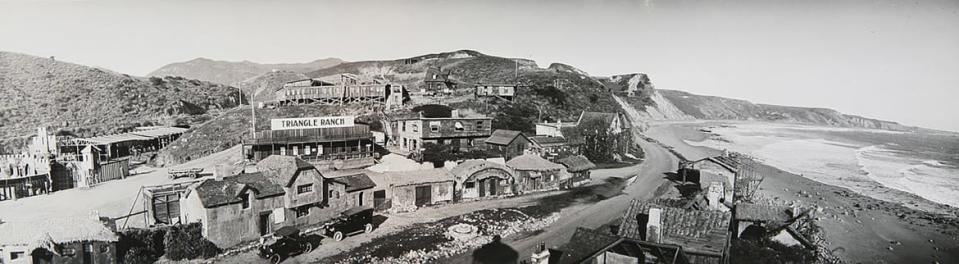

He was a theater guy through and through, but as all creatives learn, you sometimes have to give up your high-minded ideals and go where the money is. Ince dipped a toe into the film industry for the money, but he quickly became enthralled with directing and producing moving pictures. He jumped all in. He worked for many of the big names before going off to make his own movies. Not only did Ince start an independent production company, but he also created an entire studio town, Inceville, which became known for its westerns.

“The studio had 520 people on the payroll and its grounds were home to sets including a Spanish mission, a Dutch village with canal and windmill, a Western town and, of course, a Sioux Indian village,” the Los Angeles Times reported. “It was there that Ince—using a circus with 350 showmen—staged the Battle of the Little Big Horn in the ambitious three-reeler Custer’s Last Fight (1912), among other famous Westerns. For realism, Ince imported 100 Sioux Indians, many of whom had taken part in the actual 1876 battle against the 7th Cavalry.”

As the 1920s kicked off, Hearst was also embedded in the film industry. The business magnate had gotten into the industry as a corollary to his work in news—he saw opportunities in turning printed cartoons into animations and producing newsreels during the war—but by 1919 he was making movies and laying the groundwork for his own studio.

This is where the two men’s interests joined. Hearst and Ince had no doubt run into each other around town, but their association began to take a more concrete shape as the producer’s 44th birthday neared. Hearst approached Ince about going into business together. The tentative agreement was that Ince would produce a film starring Marion Davies, Hearst’s mistress. If all went well, they would think about forming a more formal partnership. The Oneida jaunt was to be a celebration of this new venture as well as a birthday party for Ince.

What really happened on that trip was this: after a day of indulging in food and drink, the already struggling Ince got really sick. He was so sick that other guests could hear his loud moans and groans from his private room and went to check on him, where they found him in great distress. It was clear his situation was critical. They immediately had him sent from the ship to shore where he received more capable medical attention, was taken to his home, and died the next day. It could have been that the rich foods set off Ince’s heart troubles, or, as other initial reports stated, he was exposed to a bad batch of bootleg alcohol. Whatever the cause, his family and physicians agreed that “angina pectoris” had tragically felled the young producer.

It was a sad story. A tragic story. But soon, it was not the only story being told. Some of the rumors that swirled around the Ince affair can be chalked up to the nature of Hollywood and celebrity. But most of them were fuelled by really unfortunate decisions on the part of those onboard the Oneida.

Unfortunate move #1: Inviting your lover’s lover to the party

Hearst was a married man. He spent weekends with his family at their country estate, San Simeon. But during the week, he was all about his lover, the famous actress Marion Davies. “To make up to Marion for choosing San Simeon over her almost every weekend, Hearst spoiled her when he was in Los Angeles, hosting lavish entertainments for her and her friends at 1700 Lexington and taking them on luxurious cruises on the Oneida,” David Nasaw writes in The Chief: The Life of William Randolph Hearst.

Davies was significantly younger than the business mogul and she was not short of things to do or people to flirt with while her lover was away. While Hearst was playing family man, she entertained interest from other areas, namely Charlie Chaplin, who was pursuing her as a diversion from his own messy home life in the shape of his 15-year-old fiancé (Chaplin was 54), who was away from town while pregnant with the actor’s child.

Vera Burnett, who was working on a film set with Davies at the time, told Nasaw that Chaplin and the actress “seemed to be very enamored of each other. They had told me if I saw Mr. Hearst come in, just to let them know. Also, they told Jimmy Sweeney, who was the prop man, to immediately notify them and Mr. Chaplin would go out the back door.”

Among the many mysteries and inconsistencies of Ince’s last sail is the guest list. But one guest who was definitely present, despite the open secret of his liaisons with the host’s mistress, was Chaplin. So, when rumors began that Ince’s death may not have been natural, people looked to the most likely cause of strife: who can imagine smooth sailing when alcohol and a torrid love triangle are combined?

The main story that quickly spread was that, in a fit of rage, Hearst tried to shoot Chaplin, but accidentally hit Ince instead. (Another, less widespread theory, had it that the newspaperman found Ince himself in Davies’s arms and took his jealous revenge.)

Unfortunate move #2: Trying to cover-up a different crime

In mid-November 1924, America was in the thick of Prohibition. But that didn’t stop the glittering classes of L.A. from enjoying their drink.

One guest on the Oneida that night was Dr. Daniel Carson Goodman who, despite his title and physician’s license, was a movie man employed by Hearst. When it was clear that Ince was not in a good way, the doctor was woken up and charged with looking after the producer while he was rushed to shore. As the dinghy sailed away, he was told to be discreet.

The secret Hearst and the other party guests wanted him to keep was not the murderous crime of one man, as the rumors would claim, but instead that of everyone on board who had unreservedly consumed illegal liquor.

‘I don’t know whether Dr. Goodman was much of a doctor, but he diagnosed it as a severe heart attack,” guest and costume designer Gretl Urban told Nasaw. “We headed immediately for San Diego. When the anchor was dropped, we all stood around as a launch was lowered. In front of us, Hearst warned Dr. Goodman not to let anyone ashore know that his patient had come from the Oneida… The unfortunate Goodman, upset by the sudden tragedy… completely lost his head and fabricated so many impossible tales and acted so super-discreet that the press and everyone else ashore were convinced he was covering up some horrendous crime.’”

Not only did Goodman’s behavior raise suspicion, but so too did Hearst’s. Early reports from one of Hearst’s own papers states that Ince had taken ill while at a party at San Simeon. Everyone knew that the party had been on Hearst’s yacht, so why would they be lying about the location? Also, Hearst and Chaplin were among the guests who initially claimed not to have been aboard that night, which was very clearly untrue and easily debunked.

Unfortunate move #3: RSVP’ing “no” to a funeral

After his death, Ince was quickly cremated—some say too quickly—and a private funeral service planned. While the family contended that the cremation had been Ince’s wish, observers were read into the decision and the timing as an attempt to destroy evidence.

But what set off the amateur sleuths even more was who did and did not show at the funeral. Davies and Chaplin were there, but Hearst decided to hole away at San Simeon. According to Nasaw, he did so hoping that his absence would calm the whispers and any negative publicity surrounding the events, but it instead fueled suspicions. The only reason to avoid the funeral of a friend, the theory went, is if you were guilty of said friend’s untimely demise.

Unfortunate move #4: Making hiring decisions with bad timing

Rumors have it that the earliest piece of evidence that something fishy happened that night was when Hearst’s own paper published a breaking story headlined “Movie Producer Shot on Hearst Yacht.”

This may have been purely fabricated given that archives of such a piece no longer exist (or were they destroyed? the gossips ask!), but it didn’t help that soon after Ince’s death, famed gossip columnist Luella Parsons got a new gig with the Hearst organization.

One debunked rumor that continues to persist was that Parsons was on the Oneida that night. She wasn’t—she was on an entirely different coast—but for decades people have speculated that she got the job in exchange for keeping quiet about what she witnessed.

In the wake of his passing, the San Diego Police quickly saw the truth of the matter. Less than a month after Ince’s death, San Diego District Attorney Chester C. Kempley issued a statement to that effect: “I am satisfied that the death of Thomas H. Ince was caused by heart failure as the result of an attack of acute indigestion. There will be no investigation into the death of Ince, at least so far as San Diego County is concerned.”

A century later, the story continues to be told in both rumor and on the big screen (via the 2001 The Cat’s Meow) that Ince’s death was not what it seemed despite the fact that the evidence clearly showed his demise was sad but natural.

Yet, to this day, whenever Ince is brought up, or Hearst and Chaplin’s names appear in the same sentence, the murder that wasn’t is inevitably mentioned. Long after the end of Prohibition, legends of the infamous party on the Oneida refuse to be forgotten.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.