How did genetic genealogy lead to an arrest in a 43-year-old cold case?

For more than 40 years it seemed like Karen Umphrey's death would forever remain a mystery.

Umphrey was found dead on Nov. 2, 1980, with gunshot wounds. Though DNA was recovered from the scene, a suspect could not be identified, and the years passed on without any answers.

It's a story that's familiar to those who work in forensic genetic genealogy, a field that has broken through the stagnation in hundreds of cold cases nationwide.

Othram, the company that assisted in the investigation of Umphrey's death, has been part of a growing movement to use genetic genealogy to solve cold cases that once seemed unsolvable.

Douglas Laming, 70, was identified as a genetic match for a semen sample recovered from Umphrey's body and has been charged with open murder.

Frederick Lepley, Laming's defense attorney, has said in court the DNA match only proves there was sexual contact between Umphrey and his client, not that he killed her. Laming has not been charged with sexual assault and told police he had consensual sex with Umphrey.

Genetic genealogy first drew national attention in 2018 with the arrest of Joseph DeAngelo, who was identified as the "Golden State Killer" responsible for 13 murders and more than 50 rapes in California between 1974 and 1986.

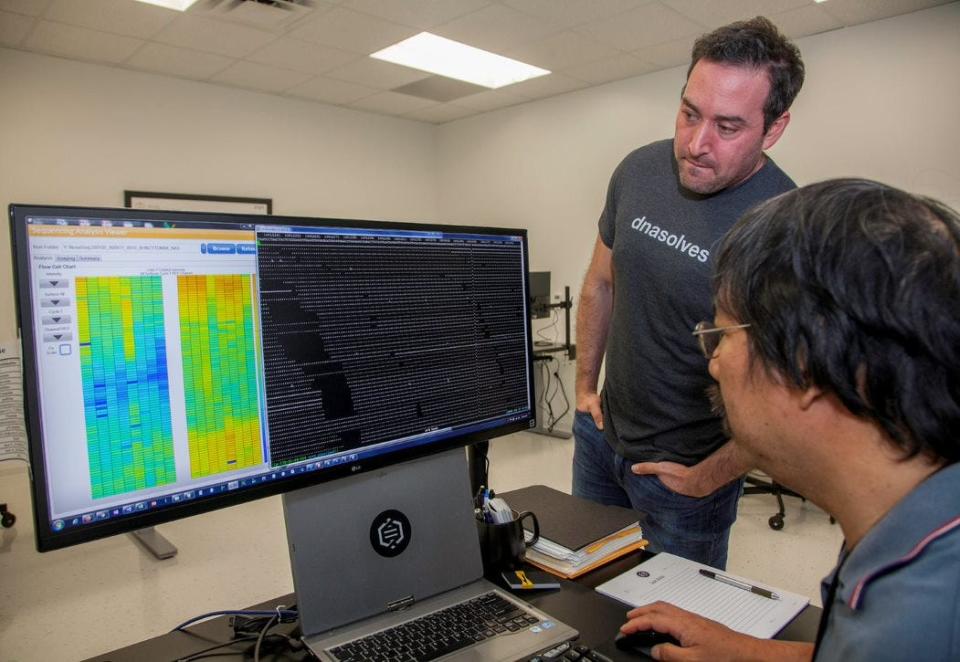

That same year, husband and wife David and Kristen Mittelman founded Othram Inc. to provide law enforcement with assistance using genetic genealogy to investigate cold cases.

In Umphrey's case, Othram only built the DNA profile. Mittelman said his company can build family trees to generate leads for the investigation, but in this case Michigan State Police chose to identify leads on its own.

Michigan State Police took notice of the use of genetic genealogy in solving cold cases and began its own pilot program about 18 months ago, Michigan State Police Lt. Kim Vetter said. The program still contracts with outside laboratories and DNA scientists for much of the lab work, but has helped facilitate the use of genetic genealogy in 20 cases since the program began.

In the past, DNA testing typically solved cases by collecting samples and comparing them to samples taken from people previously arrested. This left a blind spot open, however, when a suspect had not previously been arrested.

The process begins by recovering a DNA sample from a crime scene of an unidentified suspect, witness or victim. Law enforcement then contacts DNA repositories which are full of samples from customers who submitted them to learn about their heritage.

"There's three databases that are consented in some shape or form for law enforcement use," David Mittelman said. "There's GEDMatch, there's FamilyTreeDNA and then Othram's public database called DNASolves."

From there, investigators can see if the anonymous owner of the DNA has any relatives in the repository.

"Genetic genealogists will upload the (single nucleotide polymorphism) data to the commercially available genealogy databases that allow for law enforcement searches, then will interpret the genealogy database search results, and begin building family trees to see if any close relatives of the subject can be identified," Vetter said in an email.

How long it takes can vary, Vetter said, based on how complex a family tree is. She said the process can also be delayed because some demographics are more likely than others to have submitted DNA samples.

St. Clair County Prosecutor Michael Wendling said the ability to identify suspects with genetic genealogy has been a major breakthrough for older cases.

"It allows us to find suspects we otherwise wouldn't have found, much like fingerprint samples did 40 or 50 years ago," Wendling said.

Wendling said its also been a relief for the families in cases his office has worked on.

"In the cases that we've used it in the last year, I think it's incredibly encouraging for the families," Wendling said.

Most DNA databases do not allow law enforcement to use their collection for investigative purposes, but these three request consent from its users to have their DNA used in police investigative purposes.

Mittelman said he's worked in DNA testing most of his career, including on the Human Genome Project while working as a research assistant at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

In 2018, when genetic genealogy was in its infancy, Mittelman and several colleagues collaborated on how to use their expertise for forensic science.

"We all kept in touch over the years," Mittelman said. "DNA testing is a very complicated and specific field. It's one that everyone pretty much knows each other."

There was no shortage of business as most law enforcement offices had at least one major cold case that had not seen a breakthrough in decades.

"There are so many of these cases. Human remains, unsolved violent crimes that have some element of a homicide or sexual violence, and yet all these cases, they generally linger because there is uncertainty in what happened," Mittelman said. "The scientific tools of the day were not sufficient to provide enough clues or details, or enough certainty to solve the case. We built Othram to basically bring certainty to investigations and help close these investigations which have been languishing for years, and in some cases, decades."

Contact Johnathan Hogan at jhogan@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Port Huron Times Herald: How did genetic genealogy lead to an arrest in a 43-year-old cold case?