Did Hawaii officials botch the response to Maui wildfires?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The wildfires that have devastated Hawaii in the past week now officially constitute the worst natural disaster of its type that America has seen in a century, its death toll now at 111, surpassing the number of people killed in California’s notorious Camp Fire of summer 2018.

Tens of thousands of residents and tourists had to flee the Big Island and Maui after the blazes that erupted on Tuesday 8 August, fanned by high-speed winds from Hurricane Dora, laid waste to the historic town of Lahaina and many other locations, in some cases forcing people to retreat into the ocean to escape the flames.

Hawaii’s governor Josh Green has estimated that the island chain will require billions of dollars of investment to recover from the disaster, with the US Civil Air Patrol and the Maui Fire Department reporting that hundreds of residences and businesses have been damaged or destroyed.

Mr Green has thanked President Joe Biden and the Federal Emergency Management Agency for its support so far but it is clear the recovery effort will have to be considerable to restore the tropical paradise to its former glory and ensure it is better safeguarded against calamity in future.

Right now, the emphasis of the response remains on putting out the fires and ensuring the safety of the public, a goal complicated by stories of lootings and armed robberies taking place amid the breakdown of law and order.

However, once the crisis is contained and a degree of normality restored, Hawaiian officials could face tough questions about the extent of the island’s preparedness for the situation that unfolded.

Specifically, the public will expect answers on why its alert system failed, why expert warnings were ignored and whether domestic electricity providers played any role in the disaster.

Silent alarms

Maui is understood to have 80 outdoor sirens in place to warn locals of imminent tsunamis or other natural disasters – which are tested monthly, according to the BBC – but not one of them sounded as the brush fires broke out, officials have since confirmed.

Residents of Lahaina were initially concerned when they woke up without power on Tuesday morning but were reassured when Maui County reported at around 9.55am that wildfires raging nearby had been “100 per cent contained”, only for the blazes to be whipped up by the winds again that afternoon without further warning.

Some residents subsequently told the media they had received phone alerts but it is possible the earlier blackout played a role in limiting the dissemination of messages further afield. In many cases, it was only the smoke alarms in private buildings that notified them of the need to evacuate, leading to a panicked exodus that might perhaps have been avoided.

Mr Green announced on that the state’s attorney general, Anne Lopez, would be launching an investigation into Maui’s emergency response policies to try to determine what went wrong.

He has largely preferred to avoid blaming human error, however, saying in a statement issued on Sunday: “That fire travelled one mile every minute, resulting in this tragedy. A fire hurricane, something new to us in this age of global warming, was the ultimate reason that so many people perished.”

Announcing her inquiry, Ms Lopez said: “My department is committed to understanding the decisions that were made before and during the wildfires and to sharing with the public the results of this review.

“As we continue to support all aspects of the ongoing relief effort, now is the time to begin this process of understanding.”

Hawaii Democratic senator Mazie Hirono, addressing the matter during an appearance on CNN’s Jake Tapper Sunday over the weekend, said: “I am not going to make any excuses for this tragedy.

“But the attorney general has launched a review of what happened with those sirens and some of the other actions that were taken.”

In a press conference on 17 August, Herman Andaya, the Maui County Emergency Management Agency administrator, said that officials made the decision to send out emergency messages via phone, radio and television because they did not believe the outdoor sirens would be of use.

“Had we sounded the siren that night, we were afraid that people would have gone mauka [to the mountainside],” Mr Andaya said.

He added that their outdoor sirens are typically used for tsunamis in which residents are trained to seek higher ground. Mr Green echoed this in a press conference saying the siren is advertised as being used almost exclusively for tsunamis.

“And if that was the case, they would have gone into the fire,” Mr Andaya added.

He noted that the outdoor sirens only exist on the coastline so even for the people who live mountainside, they would have been useless to them. He also said that most people probably would not have heard the siren due to the winds and incoming fire.

Mr Andaya has since abruptly resigned, citing unspecified health problems.

Expert warnings ignored

Historically, Hawaii has rarely been afflicted with wildfires and, when they have occurred, they were most commonly ignited by volcanic eruptions or lightning strikes.

But University of Hawaii professor Clay Trauernicht, for one, had been warning of the growing dangers posed by brush fires since at least 2014, noting that the area of the state burned annually has quadrupled in recent decades.

Professor Trauernicht attributed the increase to the invasion of non-native dry vegetation, which has been allowed to colonise former agricultural lands and deforested spaces, turning them into grassland savannas that serve as ideal kindling, particularly in periods of drought.

He has called the present crisis the inevitable outcome of “benign neglect”.

His warnings were previously validated when Hawaii suffered deadly wildfires fanned by Hurricane Lane in August 2018 and again in 2019.

In the aftermath of those developments, a Hawaii Emergency Management Agency (HIEMA) risk assessment report from 2021 duly noted that: “Fires occurring as a result of and concurrent with another major threat or disaster, such as a hurricane, are particularly challenging.”

That same year, a Maui County report on wildfire prevention recommended an “aggressive plan” to replace the dangerous grass while also condemning the extent of funding available as “inadequate” and finding that the absence of any advice on “what can and should be done” in its fire department’s strategic plan amounted to a “significant oversight”.

Despite all that, there remains no specific advice for how the public should respond to wildfires on the HIEMA website, although it does concede their growing frequency.

The agency’s latest report from 2022, meanwhile, rates the risk posed by fires compared to other forms of natural disaster as “low”.

Among those making the official counter-argument against accusations of negligence so far has been Hawaii lieutenant-governor Sylvia Luke, who observed: “When we are preparing for the hurricane, we expect rain, sometimes we expect floods. We never anticipated that in this state that a hurricane, which did not make an impact on our islands, would cause this type of wildfires.”

Downed power lines to blame?

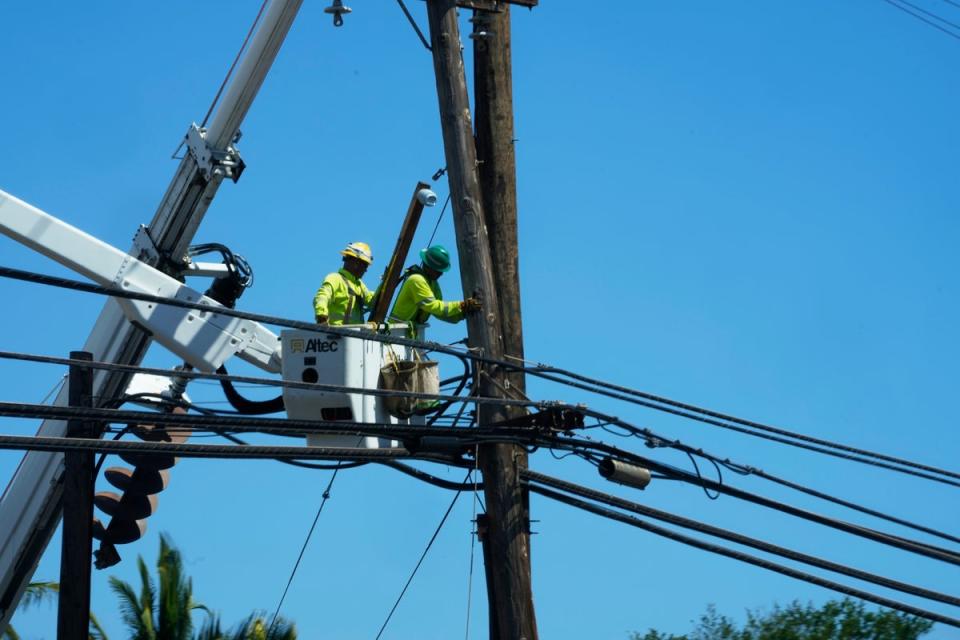

Another local institution facing criticism over the disaster is Hawaiian Electric – which supplies 95 per cent of the state’s electricity – which is the subject of a class-action lawsuit brought by three law firms alleging that downed power lines played a role in the inferno on Maui.

The complaint, obtained by Spectrum News, claims that the utility “inexcusably kept their power lines energised during forecasted high fire danger conditions”.

It argues that the National Weather Service warned on Friday 4 August that Hawaii could experience “indirect impacts” from Hurricane Dora, including “strong and gusty trade winds” and “dry weather and high fire danger”, issuing a red flag warning that Hawaii Electric, it is alleged, neglected to react to.

A Hawaiian Electric spokesperson declined to comment on the lawsuit in a statement, saying that the company does not discuss pending litigation as a policy.

“Our immediate focus is on supporting emergency response efforts on Maui and restoring power for our customers and communities as quickly as possible,” they said.

“At this early stage, the cause of the fire has not been determined and we will work with the state and county as they conduct their review.”