How did the Hawaii wildfires start?

At least 99 people are dead and thousands more have been forced to evacuate the island of Maui after deadly wildfires raged throughout Hawaii.

The fires, which are believed to be the deadliest in the US in the last century, erupted on three of Hawaii’s islands forcing visitors to flee and residents to seek emergency shelter.

Photos and videos from Maui show the destruction the fires have caused, with some neighbourhoods including the historic town of Lahaina, nearly burned to ash.

Search and recovery efforts then began as firefighters worked to contain and put out the fires. But the wildfires have sparked a frenzy of questions about how disasters like this can be prevented in the future.

Here’s everything we know about how the Hawaii wildfires started.

How did the wildfires start?

August is part of Hawaii’s typical dry season when parts of the island experience abnormal to severe droughts.

Since the beginning of August, most of Maui has been under an “abnormally dry” level of drought, according to the US Drought Monitor.

But beginning on Tuesday, 8 August, a portion of Maui escalated to a “severe drought” level making the area more susceptible to wildfires.

Though the islands are no stranger to some wildfires, the number of fires has increased exponentially over the past century due to human activity and an increase in invasive, flammable grasses, according to the Hawaii Wildfire Management Organization (HWMO).

“Nonnative grasslands and shrublands now cover nearly one-quarter of Hawaii’s total land area and, together with a warming, drying climate and year-round fire season, greatly increase the incidence of larger fires,” the HWMO wrote in a factsheet.

The dry vegetation combined with the drought conditions made for the perfect environment for wildfires.

But what may have caused the explosion in wildfire conditions is the strong winds brought on by Hurricane Dora, a Category 5 hurricane located several hundred miles off the coast of Hawaii.

The National Weather Service (NWS) issued a red flag warning to the Hawaii National Guard due to the high winds, low humidity and drought, according to The Washington Post.

The biggest utility company in Hawaii is now coming under scrutiny as questions mount if it took enough precautions to prevent a wildfire as the heavy winds began to hit Maui last week.

Attorneys representing Lahaina residents are suing Hawaiian Electric, claiming that its equipment wasn’t strong enough to handle the winds coming in over the island, adding that the company should have shut down the power before the winds struck the area, according to The New York Times.

Wildfire experts who have looked into the fires in California over the last 20 years see problems with Hawaiian Electric.

Officials on the state and local levels have not yet determined a cause for the fire almost a week after they began, but the conditions were similar to other parts of the US where wildfires have been started by electrical equipment, namely old infrastructure, high winds, and dry, easily flammable brush.

Many US wildfires start when powerlines are blown down, or when branches or other things land on powerlines leading to flashes of electricity, prompting some utility companies to shut power down ahead of strong winds.

The National Weather Service expected winds of 45 miles per hour and gusts of 60 miles per hour to hit Maui on 8 August as Hurricane Dora passed by the island about 700 miles south.

The chief executive of the Frantz Law Group, James Frantz, told The Times that “we allege that many of the regulatory laws that require maintenance of equipment were broken”.

The group is one of several firms going up against Hawaiian Electric.

“There’s got to be some accountability,” he said.

Investors in the utility company appear to be concerned as its share price dropped more than a third of its value on Monday 14 August. The company may have to pay large amounts to settle lawsuits from homeowners and businesses, and also invest in fireproofing its current infrastructure.

Stock analyst Shahriar Pourreza told The Times that “the issue becomes whether they did everything they could that was reasonable to prevent this incident”.

“Was there gross negligence, was there imprudence?” he added.

Hawaiian Electric was founded in 1891, and on Maui, it functions under a subsidiary – Maui Electric. The company is minuscule compared to the California companies that have doled out massive settlements following wildfires.

In 2022, its revenue was $3.7bn compared to $21.7bn for California’s Pacific Gas and Electric.

The chief executive of Hawaiian Electric, Shelee Kimura, said during a press conference on 14 August that they didn’t have a shutdown programme and that shutting down the power may have led to problems for people using certain kinds of medical equipment.

She noted that turning the power off would have required coordination with the emergency services.

“In Lahaina, the electricity powers the pumps that provide the water and so that was also a critical need during that time,” she said. “There are choices that need to be made and all of those factors play into it.”

On Saturday, the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the Pacific Disaster Center said that more than 2,000 structures had been damaged or destroyed on Maui, with an estimate for rebuilding costs being $5.52bn.

Mr Pourreza noted that Hawaiian Electric could be liable for more than $4bn. In June, the company had $314m in cash.

Lightning strikes have also caused some wildfires in the US West but NASA lightning detectors didn’t see any such activity around Hawaii when the fires began.

Whisker Labs is a private firm that monitors the electrical grid in cities for issues which may lead to a home fire. Its data seems to show major incidents on powerlines close to where the fire is thought to have begun, according to The Times.

Late on 7 August and into the early hours of 8 August, the data shows that power lines started to lose voltage, which can occur when branches and other types of vegetation begin to affect wires, lines, poles, or other types of equipment.

The firm said it has nearly 1,000 sensors in Hawaii and around 70 on Maui. While all of the sensors on Maui sensed a fault, the strongest one was near Lahaina.

Its co-founder and chief executive Bob Marshall told The Times that it lasted eight seconds, “which is an eternity in electrical grid time”.

“Something on the grid was very unhappy for eight seconds and trying to recover from a shock,” he added.

In a 2022 regulatory filing, Hawaiian Electric outlined efforts to reduce the risk of fires. It stated that the firm was “hardening” poles to be able to handle strong winds and that it was removing vegetation, citing Lahaina as a priority area.

Safety measures take time and may be expensive for a company to carry out.

Standford climate and energy policy scholar Michael Wara told The Times that burying power lines costs between $3m and $5m for every mile, with those costs usually added to bills for customers. The rates for electricity in Hawaii are already the highest in the US, the US Energy Information Administration states.

“Why did they not do the cheap thing, turn the power off?” Mr Wara asked.

Where did the wildfires start?

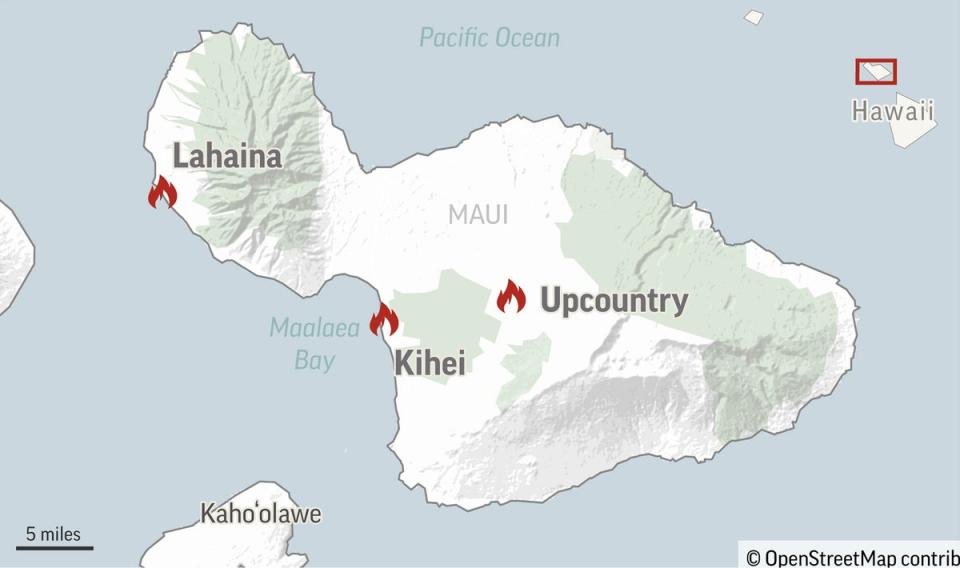

The fires broke out earlier this week on three islands: Hawaii, Maui and Oahu with the deadliest fires being on Maui.

It is unclear where the fires first began but from the time they started, they moved extremely quickly.

The town of Lahaina, located in western Maui, was seemingly hit the hardest with more than 270 structures burned.

On Saturday 12 August, the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the Pacific Disaster Center said that about 2,000 structures had been destroyed or damaged on Maui.

The speed at which the fire in Lahaina moved on made it difficult for firefighters to contain the massive blaze.