Wild idea: Should we return the Caloosahatchee to its natural state?

For more than a century, the Caloosahatchee has led a double life.

Though commonly called a river, as far as the federal government is concerned, it’s a canal: a manmade, man-managed waterbody connecting Lake Okeechobee to the Gulf of Mexico. With a deep-dredged channel straight enough for ship traffic, it’s the western leg of the cross-state, 154-mile-long Okeechobee Waterway, a fact duly noted on the bridges traversing it.

Now separated by U.S. Army Corps of Engineers-run locks into three tidy segments, the river’s salty, tidal portion is walled off from its upper freshwater reaches.

Yet human intervention hasn’t entirely tamed the Caloosahatchee, and traces of its once-wild character remain. As environmental restoration gains momentum in other parts of the state and nation, from the Kissimmee near Orlando to the Klamath out west, work is quietly happening around the Caloosahatchee as well to return it to a more natural state.

Because in addition to making the watershed more human-friendly, all that reengineering sickened the river itself.

As longtime environmental scientist and water quality advocate Bill Hammond points out, each segment is essentially a huge, pooled lake, corralled by mechanical weirs. And as pool owners can tell you, fertilizer plus heat turns water stagnant green, which happens reliably to the river, when runoff spawns algae blooms.

The question now: If people broke the Caloosahatchee with the best of intentions more than a century ago, can they put it back together? To use the contemporary term, can the river be rewilded and returned to a more natural state?

No one’s suggesting a pre-1800s river is possible, but advocates argue much can be done to undo the collateral damage of the river’s taming.

What does the C in C-43 stand for? Hint: Not Caloosahatchee

What humans did to the river is best seen from above. At altitude, it’s a dark line with an angle here or there - nothing like the sinuous river seen on old maps. The once-upon-a-time Caloosahatchee meandered westward, side-winding from the state’s center to the Gulf of Mexico over more than 70 miles. Between east Lee County’s Olga and the Hendry County seat of LaBelle alone, 37 of these remnant twists and turns remain (image), now sliced by the channel and known as oxbows, for their resemblance to the U-shaped harnesses used to hitch up cattle.

With the bends left to the side, it’s now a nearly straight shot from Lake Okeechobee to Cape Coral through a canal (in fact, in C in the river’s official federal name, C-43, doesn’t stand for “Caloosahatchee,” but for “canal”) deep enough to float big boats and ample enough to carry rushing floods from surrounding land plus Lake Okeechobee out to sea.

That’s all by design.

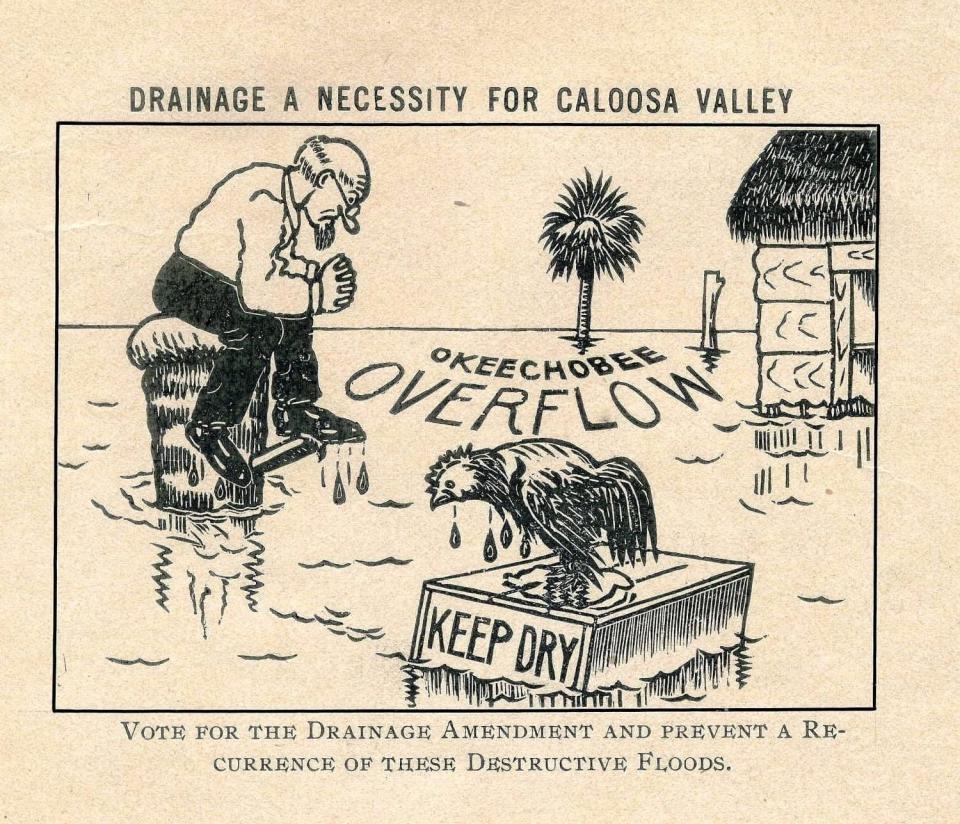

When people started changing the Caloosahatchee system, they focused on transport and flood relief, bending what nature had created to suit their needs.

Disston: Drain, ditch, dredge, dynamite

If not for large-scale dredging and drainage, Southwest Florida as we know it wouldn't exist.

With much of the region swampy or submerged, early farmers began digging canals and ditches so they could plant everything from eggplants to pineapples. After the farmers came Northerners seeking a piece of paradise, which also required drainage and flood control.

They got it. Into Lee County's 283 square miles of inland waterways, you could fit Bonita Springs, Cape Coral and Fort Myers.

It started in the 1880s, when Philadelphia developer Hamilton Disston began draining wetlands around Lake Okeechobee. He linked several smaller lakes to Okeechobee, then dredged a canal to the Caloosahatchee, creating a seamless waterway from lake to Gulf.

Even so, massive hurricanes in the 1920s devastated the region, claiming thousands of lives and sending strident demands for more flood control to Washington, DC. In 1930, Congress began building a dike around the lake and increasing the Caloosahatchee's capacity.

All the locks, canals and barriers built to restrain the region's waters created a need for repair, restoration, and improvement projects that continues to this day.

'Why the hell can’t we just put it back?'

Originally, the Caloosahatchee was part of a north-to-south moving system, explains long-time river champion Rae Ann Wessel.

“As creation made it, (it was) a linear system that flowed from the north, pulling Kissimmee water into Lake Okeechobee, which eventually closed up and became an inland sea, and a separate freshwater lake which overflowed south to the Everglades,” she said. “There was a natural seasonal overflow through marshlands out of Lake Okeechobee that would come towards the west: Lake Hicpochee, Bonnet Lake, Lettuce Lake and Lake Flirt and then the Caloosahatchee started at the western edge of Lake Flirt and made its twisting winding journey to the Gulf.”

At some times of the year, water flowed from lake to Gulf; sometimes it didn’t.

“The bottom line is we took a massive natural system, engineered it to be a major drainage, water supply and recreational resource, and in the process lost the ability for the system to work as it needs to work,” said Wessel, the retired natural resources policy director for the nonprofit Sanibel-Captiva Conservation Foundation.

All of which, she says, begs the question: “Why the hell can’t we just put it back? That’s the knee-jerk: This isn’t working; let’s undo it response,” she said.

But you’ve got to recognize the constraints, Wessel says. “This is a massive drainage system … a relief valve.”

Because as humans were changing the Caloosahatchee and the St. Lucie to the east, farmers were moving in south of the lake, now that it was safely (mostly) behind a huge dike.

That left a challenge for those who would rewild the Caloosahatchee: “The Everglades Agricultural area has been designed in such a way – and not to pick on agriculture – but that is the bottleneck. The water has to go south, so until and unless you remove that bottleneck and reopen the Everglades to be a system … you’ve got to have the ability to move massive amounts of water in a quantity and timing that will take the pressure off the two estuaries,” she said. “You can’t ever drain through a blocked pipe (and) with Lake Okeechobee, you’ve got a rock wall (the Herbert Hoover Dike) and there’s only so much you can do with that unless you could open up the bottom side of the lake, which would be all Everglades Agricultural Area.”

For whatever reason, says FGCU Professor James Douglass, who works in the department of marine and earth sciences, the idea of rewilding the Caloosahatchee hasn’t caught fire here yet. “I think it could catch on, but there’s a lot of work and outreach we’ve got to do to change the attitudes that lead to water pollution.”

‘How Mother Nature can recover’

Yet elsewhere, restoration successes hearten river advocates.

The Kissimmee River’s transformation from Caloosahatchee-style straight-shot ditch to a once-again meandering course has become the restoration success story poster child.

Yet it’s by no means the only example, says Chauncey Goss, governing board chair for the South Florida Water Management District, which helped acquire the necessary land and partners with the Corps on the management of both rivers.

Besides the Kissimmee restoration, Friends of the Everglades Executive Director Eve Samples points to an even bigger project. Fixing the once algae-plagued, fish-poor, Klamath River in California and Oregon involved the removal of four dams over its 250-mile course. “The before and after shows how Mother Nature can recover,” Samples said. “We can reverse some of the overengineered damage if we do it in a way that works with Mother Nature.”

The project could be instructive for Florida, Samples says. “If there was the political will, the state could revise that damage,” especially if there were willing sellers, “who’d come to the table to purchase land for the greater good.”

Piecemeal is not a dirty word

The Caloosahatchee is part of the Everglades, which happens to be undergoing the largest environmental restoration in the planet’s history. Restoration, though – not rewilding. Many components of that project are intensely engineered, attention-getting marvels like giant reservoirs around the lake, which divert focus from the Caloosahatchee, says Matt DePaolis, environmental policy director for the Sanibel-Captiva Conservation Foundation.

The water management district is building a huge reservoir (also called the C-43) west of LaBelle that could store 170,000 acre-feet of local basin stormwater runoff and releases from Lake Okeechobee. The aim is to reduce the volume of discharges from Lake Okeechobee to the river's estuary during the wet season and provide freshwater flow to the estuary during the dry season.

“What I don’t want to happen is that once the EAA reservoir is up and running, once the C-43 reservoir is up and running, for everyone to pat each other on the back and go, ‘OK, now what?’ I want us to have a game plan for how we’re going to fix the other half of our water issues that don’t come from Lake Okeechobee and do come from the watershed … We’re still going to have water issues in the Caloosahatchee and everyone’s going to turn around to each other and say, ‘What’s going on? I thought we fixed this.’

“The lake is only half the problem,” he said. “We saw massive, damaging discharges with zero releases coming from the lake – which was all watershed – over the summer, so it’s not a problem that is going to be solved by the Army Corps alone. With us just racing to squeeze every drop of development we can out of areas around Lee County, around the Caloosahatchee watershed, we really need to be taking into consideration what we’re doing and how we’re doing it so we can have intelligent growth in a way that makes us more robust going into the future, not the opposite.”

There’s no theoretical reason why something like Kissimmee restoration couldn’t be done for the Caloosahatchee, DePaolis says, but theory and practice are two different things.

“I think it would be a matter of time, money and willpower to get it done,” he said. “And absolutely we would benefit from having oxbows, from doing some of that rewilding, slowing down the water, providing limited filtration, providing aquifer recharge. But land down here gets more expensive every day.”

Why not just unplug?

“We are so far removed from what the Caloosahatchee looked like before Hamilton Disston brought his dredges down here that restoring it to that state would require injuring (he’s using that term in a legal sense) a lot of people who exist in the area now,” he said. “That’s not to say that if the will of human ingenuity were solely devoted to this project we couldn’t do it, but that would mean Army Corps ceding a bunch of control they have, and it would mean relocating people … I think we are pretty far removed from any practical ability to return it.”

But there’s a key concept that sometimes gets forgotten, DePaolis says: “It doesn’t necessarily need to be all or nothing.

“There’s a tendency to want to solve everything all at once with one big project (but) I think we have solutions we can address in a more piecemeal fashion to make incremental progress forward,” he said. “Realistically, I don’t know if we’re going to be able to buy enough land to build another C-43 reservoir … essentially a giant box of water that now you’re chemically treating with alum, and scaring the neighbors who now live next to a 23-foot wall of water, it doesn’t strike me as the best solution.”

Instead, he suggests, “You could add filter marshes on the side of the Caloosahatchee, you could acquire more tiny parcels of land to build little parks around filter marshes and tinier storage.

“If you put in a filter marsh with shade trees where people can walk their dog and they see this is not only something they get to enjoy and use, they see it’s something having a positive effect on the water quality and the water in their environment as well, that strikes me as an easier lift. Even if you have to do that 30 times instead of one gargantuan lift, I think you’re making progress.

“It’s great to start at the point of saying, ‘Let’s rewild the Caloosahatchee’ but when you meet with resistance, I think it’s important to have fallback and compromise positions that you can still work towards without people saying, ‘Well this is a pipedream; we’re never going to do it so let’s go back to a box of water with chemical treatment or just talking about it without making any progress.’

“A bunch of little numbers or one big number will still add up the same.”

Caloosahatchee rewilding, past, present and future

Here are some ideas that could help the river:

Living shorelines: FGCU Professor Douglass sees much potential in oyster restoration, “because oysters are so hardy, but their reefs have been harvested away to nothing, so one of the limiting factors to their reestablishment might just be having something for them to settle on. And the concrete bulkheads of the shoreline are just not doing it. He points to an innovative project in Naples Bay that might transfer conceptually to the Caloosahatchee.

“One of the neat things about that is it recognized that one of the limiting factors were boat wakes that were breaking up the oyster reef before it could grow,” he said. “So, they included not only the usual piles of rock and shell but a more serous concrete barriers that broke the waves and that seemed to be the missing ingredient to get that restoration to work, so I feel that approach could have a lot of promise in stretches of the Caloosahatchee.”

Grassy water: It’s a mouthful, but The Lake Hicpochee Hydrologic Enhancement Project of the South Florida Water Management District is already at work. In and around the footprint of the marshy Glades County lake that once topped 7,700 acres near the former headwaters of the Caloosahatchee, it stores and spreads out water, which reduces harmful discharges to the river and provides habitat for wildlife. With the first phase complete, the second is underway and should be finished in coming months, says Principal Scientist Anthony Betts. “Even though it’s primarily for storage, we do see a lot of water quality improvements as well.”

The idea is to capture and detain water that would otherwise flow to the river, “so we’re giving the plants an opportunity to remove phosphorus, sedimentation, things like that, so the water leaves this project cleaner than when it came in.”

On again, off again oxbow work: With its gentle curves, ancient live oaks and postcard-perfect Spanish moss, the Caloosahatchee’s oxbow No. 10 sums up the appeal and challenges of the historic river. Just west of the Alva bridge, it’s the longest in the river and contains the historic English homestead, as well as the pioneering family’s still-working citrus groves.

“It’s so scenic, and there’s all this family history, so to me, that is the jewel of the grouping,” said Rae Ann Wessel. “But the upstream end of it is getting filled in … it’s at kind of an awkward angle for flow to come in and keep it cleaned out.”

She’d like to see some water diversion to help the flow keep the curve cleaner. Mechanical harvesters for the aquatic vegetation that builds up would be good too, as would an effort to compost it into a soil amendment – a potential win/win for river lovers and gardeners, Wessel says

Currently, there’s no concerted nonprofit or agency effort to restore the river’s oxbows as there was two decades ago. In 2000, she got a $2 million grant from the Army Corps grant to work on oxbows.

That is, until the Gulf War broke out “and they pulled all the funding,” she said. But she hasn’t given up hope. Things that didn’t gain traction last time around may yet, she says. “You just keep trying You keep pushing buttons; people like me move on and people that were against us move on, so maybe the new reality is that faced with the current conditions, the right people and the right ideas will bubble to the top.”

The News-Press archives contributed to this report.

This article originally appeared on Fort Myers News-Press: Rewilding the Caloosahatchee: River at risk could benefit from nature