Did you know? One of the country's first families of Black tennis started in Indianapolis

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

INDIANAPOLIS – Sometimes you tell a story and see where it goes. You start where you started, with a small news item in the Indianapolis Recorder about a tennis scholarship with a May 1 application deadline, and then you just go. Before you know it, it’s 1951 and you’re downtown at Flanner House, handing over a check for $3,000. And then you’re at Fort Benjamin Harrison, watching this tiny little Black woman – “Mother Minnefield,” they called her – supervising almost 150 people, most of them white men, which is quite something in the 1960s.

Pretty soon you’ll be at the courts of Riverside Park, kicking butts and taking names, then at Crispus Attucks, then at Anderson High, where you’ll wait outside restaurants even as you’re blazing trails. Rest? Never mind rest. You can do that later, because first you have state championships to win in Illinois, then a historic NCAA title to win at Michigan. Ever been a ball boy – or ball girl – for a match between Venus and Serena Williams? You’re about to do that.

Along the way you’ll wonder how come you never heard about Kevin Minor, how come you never knew one of the first families of Black tennis in the United States – yeah, I said it – got its start here in Indianapolis. How come you didn’t know one family member is smiling at you five times a week from the studios of WISH-TV, or that another family member is a future athletic director in Division I, most likely in the Big Ten?

Pay close attention and you might even learn a little Italian along the way, but only if you have a passport. Because you’ll be traveling to England.

Where did this story, this family, come from? And why are you hearing about it now, anyway? Because it’s been just 11 months since Kevin Minor died. The family started a scholarship in his name. It’s called the Kevin Minor Legacy Fund, it’s for promising junior tennis players in the Midwest – girls only; Kevin was the ultimate #GirlDad – and the deadline to apply for the inaugural grant is May 1. If this scholarship would benefit someone you know, stop what you’re doing and visit www.theminorlegacy.com to apply now.

But hurry back. We have places to see.

Plus that food bank to start in Muncie.

A life of small sacrifices

Kevin Minor was good at tennis, playing a bit at Arlington High, but he was better at the books. Graduated from high school at age 16. Salutatorian. Went to Purdue and studied computer and electrical engineering. Got a job at Motorola, right out of school, and stayed there until he died suddenly on May 17. Heart attack. He was 54.

By then Minor was living outside Chicago, small town of Mundelein, Ill. By then he and his wife, Michelle – another decent tennis player in high school, another Purdue grad, another engineer – had put their three girls through college. Well, really, tennis put them through college.

Kevin and Michelle put them through junior tennis.

It’s an expensive sport to play as a kid, especially as you get better and outgrow what your parents can teach. Get really good, as Kevin and Michelle’s three daughters did, and the bills can be untenable. A Bloomberg Businessweek story estimated the family of a nationally competitive junior player will spend $40,000 a year on travel, coaching and equipment, and that story was written in 2015. Think it’s gotten cheaper? Think the pandemic helped?

“There were years growing up,” says daughter Jasmine Minor, “where I was in a different state or country every two weeks – year around. Roughly 99% of the families in the world could not afford this sport, if you think about it. My parents worked extraordinarily hard. They managed their money.”

Kevin and Michelle met at Purdue, married right away, had their first girl soon thereafter. Michelle dropped out to take care of Kristina, but around the time the baby turned 1, with Kevin now working for Motorola in Chicago, Michelle went back to Purdue. She’d come home on weekends, but during the week Kevin was working and arranging childcare.

They were Purdue-educated engineers, with jobs to match. Michelle works in the automotive industry, and she explained what she does, but listen, I’m a sportswriter from Mississippi and my ears were glazing over. All I know is they made fine salaries, but raising one tennis prodigy is expensive, and they were raising three. They didn’t take a true vacation for more than 20 years. They worked overtime, used their vacation and PTO days to travel to tournaments, and at one point Michelle was commuting from Newport News, Va., because that’s where the salary was.

It was a life of small sacrifices, every day for 20 years: Michelle working early morning hours to be done by 1 p.m. to get a girl to practice, or taking off a full year to home-school Jasmine. Kevin spackling every hole in every schedule. Holidays on the road. Brief reunions in airports, Kevin taking one daughter to a tournament here, Michelle going with the other two girls there, layovers scheduled at ATL or DFW for a family lunch.

Kevin and Michelle raised the closest family you ever saw. They raised three daughters ready to conquer the world, and not just in tennis.

They won state titles, made NCAA history

“We all gladly sacrificed, but we all did it together – Team Minor,” Michelle says. “Kevin and I would split up to cover each of the girls' events, and if one daughter was free, she’d go to her sister's matches. We did it all together, so I'm sure growing up the girls sacrificed also, but we wanted this to be all about the family. Looking back now, I think their tennis experience helped mold them all into successful women.”

You could say that.

>> Kristina Minor won more than 100 singles and doubles matches at Illinois. She has a bachelor’s from Illinois, a law degree from Marquette and a master’s in business administration from Rutgers – getting that last one while working as an assistant AD for compliance for the Scarlet Knights – and now is senior associate AD for compliance and regulatory affairs at Northwestern. She’s just 34. She’ll be an AD somewhere, and it won’t be long.

>> Jasmine Minor, 29, won the Illinois state singles title as a senior, then played at Georgia Tech – going 25-11 as a freshman – and Oregon. She majored in business, got a master’s in broadcast journalism at Northwestern, finished top 10% of her class, you know the type. Yes, that’s her on WISH-TV, an investigative reporter and weekend anchor with two Emmy wins among nine nominations. Didn’t know about the tennis, did you?

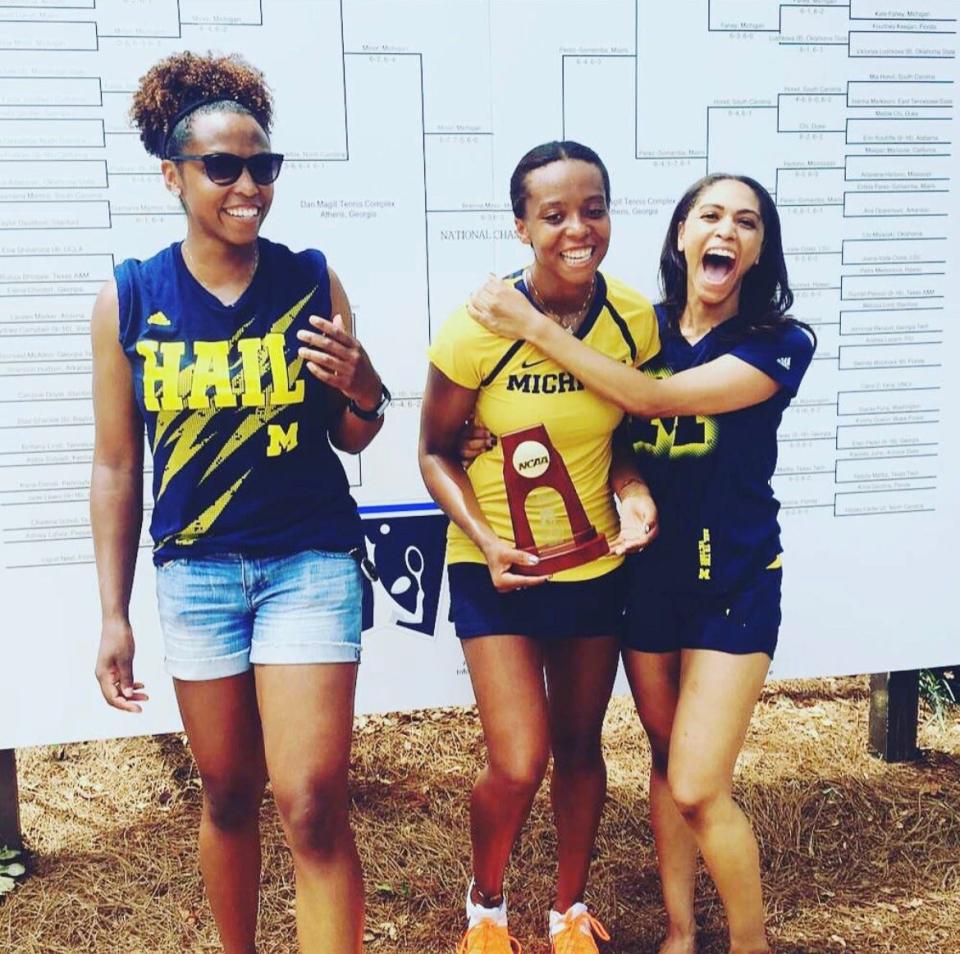

>> As for Brienne Minor, the baby sister, she’s the history maker. She also won an Illinois high school state championship, then won the NCAA championship at Michigan, becoming the first Black woman in Division I history to win the singles title. That was 2017. She was a sophomore. She’s 25 now, a pro player who works in television on the side. Behind the scenes, producing, things like that. That’s her way.

We’ll see how long that lasts. This is not a family that stays behind the scenes for long. Go back two generations, then three, then four. No, go back five generations, to Mabel Augusta. That’s where this family, this story, put down roots here in Indianapolis.

'Mother Minnefield's' food bank

On one side of the Atlantic, Mabel Augusta is handing a $3,000 check to the president of Flanner House, which provided social services for the poorest members of Indianapolis society. There’s a picture in the IndyStar and everything: June 8, 1951. She was president of the Women’s Improvement Club of Indianapolis, which spent two years raising those funds, so many nickels and dimes, for the Flanner House nursery. Mabel Augusta is the great-great-grandmother – maternal side – of this tennis family.

On the other side of the Atlantic, a bilingual young Italian woman named Eufemia Lorenzetti is in England, working as a technical translator, where she meets a dashing young U.S. Army soldier overseas for the Korean War. He’d gone to Purdue. His name is John Minor. Those are the grandparents (paternal side).

The family trees merge when Michelle Minnefield meets Kevin Minor at Purdue in the late 1980s. By then Michelle’s great-grandmother, Mabel Augusta, had long passed her tenacity to her daughter, Hazel Minnefield, who worked in finance and personnel for three decades at Fort Benjamin Harrison, practically running the place, then “retiring” and getting busy. She became a legendary volunteer in Anderson, where her father, Lee Myers, became the town’s first Black doctor in 1920. The “Hazel Minnefield Award” is given annually to a tireless volunteer in Anderson.

Hazel, or “Mother Minnefield” as she’s known around there, helped found the East Central Regional Indiana Food Bank in 1983, and served as the outfit’s executive president for its first five years. She took what she’d learned as a Gleaners volunteer and built a program that, by 2021, made possible almost 8 million meals every year.

“There would be no Food Bank without Hazel Minnefield,” The Muncie Times quoted a prominent Anderson banker at her retirement party in 1989.

Damndest tennis story you ever heard, but these are the things you discover after reading about the Kevin Minor Legacy Fund in the Indianapolis Recorder on April 14 and start to wonder where a man like this – an “Indianapolis native,” the story says – comes from, and why you’re hearing his name only now.

The WWII vet, and the van outside the restaurant

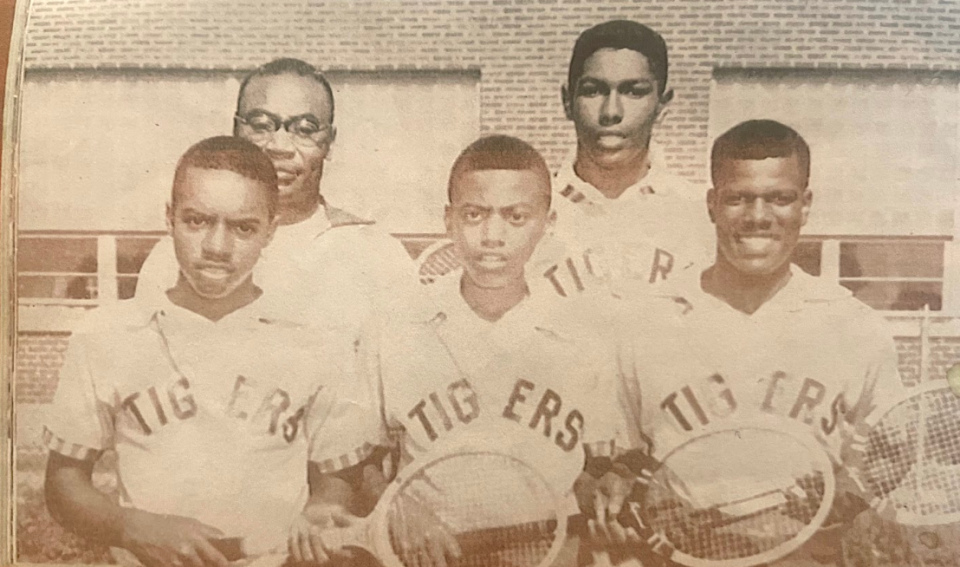

The search for the legacy behind the Kevin Minor Legacy Fund leads to Mabel Augusta, and to Hazel Minnefield, and to Hazel’s son, James, who played on the first all-Black tennis team in Indiana. That was 1955 and he was a freshman at Crispus Attucks, the year Oscar Robertson and the Tigers became the country’s first all-Black team to win a state basketball title, and the year James Minnefield won the Riverside Park and city boys tournaments.

The family moved to Anderson, where in 1956 James became the first Black tennis player at Anderson High. In those days, when the team was on the road to play schools in smaller towns around Indiana, Anderson coach Dane Pugh parked the team van outside the restaurant and went inside alone. A hall of fame coach and U.S. Navy veteran of World War II, Dane Pugh broached zero nonsense. He’d go inside, then come back for his players. He never told them why.

“I didn’t find out until years later he was just making sure I could go in with no problems,” says James Minnefield, now 83.

James played a year on the Purdue freshman tennis team. He doesn’t know if he was the first Black player at Purdue – “I just know in all my years of juniors, high school, college, I never played another Black player,” he says – but his career ended after one season.

“Ran out of money,” he says, so he joined the U.S. Army, got a job at the Guide headlights factory in Anderson, got married. Twenty years after he became the first Black boys tennis player at Anderson, the oldest of his three daughters, Daphne, was Anderson’s first Black girls player. Daphne became an oncology nurse in Indianapolis. Her daughter, Kylee Johnson, starred on the tennis team at Lawrence North and Ball State.

The ripples keep going. Daphne’s younger sister, Michelle, married Kevin Minor. They lived outside Chicago, where their three daughters were prodigies while Kevin worked for Motorola and served on the boards of the USTA districts of Chicago and Midwest. Go back if you can and find video from Nov. 17, 2004. Venus and Serena Williams were holding their Williams Sisters Tour to raise money for the Ronald McDonald House. They stopped in Chicago for an exhibition at the UIC Pavilion. See those ball girls, crouching on opposite sides of the net? That’s Kristina and Jasmine Minor.

This is a family of achievers and winners, quiet trailblazers and fierce advocates going back five generations. Trace the line from Mabel Augusta, who moved here in 1937 after graduating from Knoxville College and became the only Black employee of her downtown law firm, to great-great-granddaughter Brienne Minor, the history-making 2017 NCAA singles champion from Michigan.

Where does a family line so bold come from? Why is the legacy behind the Kevin Minor Legacy Fund one of such strength, such service? This is what I’m asking James Minnefield. He’s pausing. It’s like I’ve asked him to explain why his heart pumps blood.

“I don’t know,” he finally says. “It was just something that happened. Part of our family heritage, I guess. I thought that was what we’re supposed to do.”

Find IndyStar columnist Gregg Doyel on Twitter at @GreggDoyelStar or at www.facebook.com/greggdoyelstar.

For more information on the Kevin Minor Legacy Fund for girls tennis players under 14, visit https://www.theminorlegacy.com/. Deadline to apply is May 1.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Kevin Minor Legacy Fund doesn't begin to tell tennis family's legacy