Did Lizzie Borden use an alias? 5 facts you never knew about Fall River's infamous murders

FALL RIVER — On the morning of Aug. 4, 1892, a murderer brutally butchered a married couple in their own home in an act of violence whose viciousness stunned police and the city at large into disbelief, captivated the world in horror, and changed Fall River history forever.

Lizzie Borden, accused of murdering her father Andrew and stepmother Abby, was the only suspect ever charged in the Second Street slaying. To the public, the idea of this prim, upper-class, Sunday-school-teaching matron hacking two relatives to death with a hatchet was an irony too delicious to ignore, and the Borden murder case became a worldwide media sensation — one that dogged Lizzie to the rest of her life, even after she was acquitted.

Why are people still fascinated? Here's why Fall River's infamous legend Lizzie Borden will never die

The killer of Andrew and Abby Borden has never been found, and their slaying remains one of the most notable unsolved crimes in American history. One hundred and 31 years, hundreds of studies, documentaries, novels, fictionalized films, songs and a ballet later, Lizzie Borden’s story still fascinates people.

Here are five little-known facts you may not have known about Lizzie Borden:

Lizzie Borden has relatives with a macabre history too

In May 1831, housewife Hannah Borden Cook went to the banks of the Quequechan River to fetch some sand, used to scour her pots. While digging, she made a startling discovery: an intact skeleton buried in a sitting position, wearing a brass breastplate, a belt of brass tubes, near a quiver of arrows tipped with brass arrowheads. The archaeological find was a media sensation, and it was placed in the Fall River Atheneum, a private library inside Town Hall. Some speculated it was the body of a Native American warrior, a Portuguese explorer to the New World, a Phoenician that somehow made it across the Atlantic — but Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in 1840 wrote a poem imagining it to be a Viking warrior, and that myth has stuck ever since. Fall River’s Great Fire of 1843 — a devastating blaze that destroyed much of downtown and gave rise to the city motto “We’ll Try” — destroyed the Atheneum and the skeleton inside, so its identity will never be known.

The Lizzie connection? Hannah Borden Cook was Andrew’s aunt, making her Lizzie’s great-aunt. Cook found that skeleton about 700 feet from the house where her nephew lived and was murdered.

A cut above: 11 ways pop culture took a whack at the legend of Fall River's Lizzie Borden

Andrew and Abby Borden had open-casket funerals

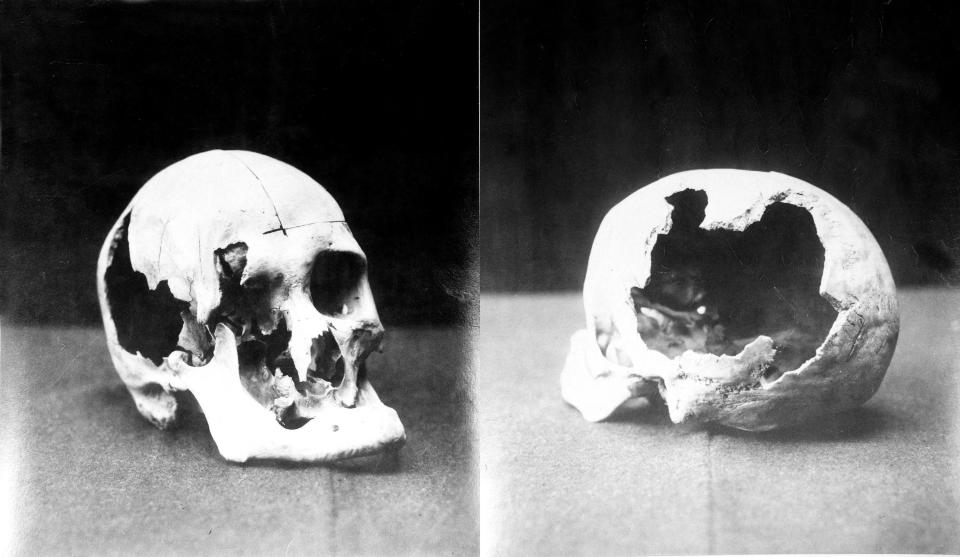

Whoever attacked the Bordens focused on their heads — and she (or he?) went buckwild.

According to Dr. Seabury Bowen, the Bordens' physician, Abby was making a bed on the second floor when the murderer attacked her, striking her two or three times from the front. She turned and fell, then “the fiend chopped her head as if it had been a cake of ice. … One glance blow cut off nearly two square inches of flesh from the side of the head.” A medical examination said “the head was chopped into ribbons of flesh and the skull broken in several places.”

Andrew was similarly savaged, the killer having rained heavy blows upon his face from above as he slept in the living room. The attack broke open Andrew's skull and jaw, leaving him a broken, bloody wreck. “Physician that I am and accustomed to all kinds of horrible sights, it sickened me to look upon the dead man’s face,” Bowen said at the time. “I am inclined to think that an axe was the instrument used. The cuts were about four and a half inches in length and one of them had severed the eye-ball and socket.”

Still, two days later, in that same living room, the Bordens were waked for about 75 mourners, according to the contemporary account of reporter Edwin Porter, author of “The Fall River Tragedy.”

“The bodies of the victims were laid in the caskets with the mutilated portions of the head turned down, so that the cuts could not be noticed,” Porter wrote. “The caskets were open and the faces of both looked wonderfully peaceful.”

No one knows for sure what the Borden murder weapon was

The teasing nursery rhyme claims Lizzie Borden took an axe. Rudimentary forensics at the time determined the murderer likely used a hatchet. Some people believe the murder weapon might've been a clothes iron.

The Fall River Historical Society contains in its vast collection of Borden evidence and memorabilia the “handle-less hatchet,” found in the basement of the Borden home and considered a possible murder weapon. However, even the society curators acknowledge it’s most likely not the Bordens’ instrument of death, since it contained no traces of blood and only one non-human hair.

So what was the murder weapon, and what happened to it? No one knows.

Message from beyond: Lizzie Borden letter delivered 126 years later — to the Fall River Historical Society

Lizzie and Emma Borden offered a reward for the killer

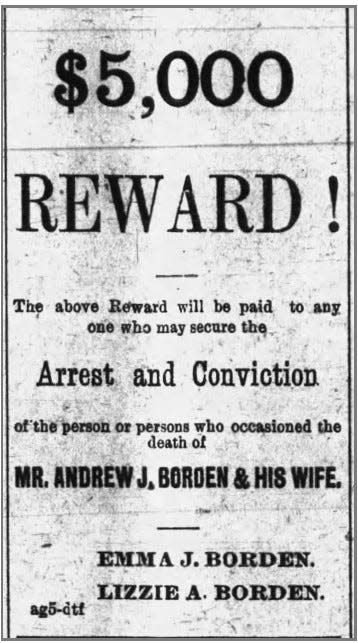

On the day after their father and stepmother’s killing, the Borden sisters put a bounty on the murderer’s head.

“$5000 Reward!” read their newspaper ads. “The above Reward will be paid to any one who may secure the Arrest and Conviction of the person or persons who occasioned the death of Mr. Andrew J. Borden and his wife.”

Those ads ran regularly in Fall River newspapers even while Lizzie was arrested and charged with the crime. They ran while Lizzie was jailed awaiting trial, and they ran during her trial and after it. In fact, the ads were published as late as October 1893, months after Lizzie was acquitted of the crime.

Despite the offer, investigators never seriously considered any suspects besides Lizzie, since the crime was so baffling — two murders in broad daylight in a house with other people inside, on a well-traveled street, with no apparent motive. If Lizzie didn’t do it, then police were stumped.

That $5,000 reward wasn’t chump change, either — in today’s money, it would be worth about $170,000.

Lizzie Borden changed her name more than once

Most people familiar with the case know that after her trial Lizzie decided to go by Lizbeth in a futile attempt to shake off the stigma around her. It’s not her birth name, but that’s the name she’s buried under in Oak Grove Cemetery.

Late in life, Lizzie is believed to have also used the name "Mary Smith Borden" — possibly the most bland alias ever — when seeking medical treatment to avoid publicity. In 1926, Lizzie was 65 years old and in declining health. At the advice of her doctor, she had what is believed to be gall bladder surgery, and was given a private room under this alternate name at Truesdale Hospital. In fact, the hospital’s founder, Dr. Philemon Truesdale, performed her surgery.

“While Dr. Truesdale knew the name of the patient, the members of his surgical staff were completely unaware of the true identity of the individual lying on the operating table,” wrote Fall River Historical Society curator Michael Martins and assistant curator Dennis Binette in “Parallel Lives,” a history of Borden and Fall River during her lifetime.

They added that Truesdale let his first assistant in on the secret afterward, asking him, “Do you know whose belly you just had your hands in?”

Dan Medeiros can be reached at dmedeiros@heraldnews.com. Support local journalism by purchasing a digital or print subscription to The Herald News today.

This article originally appeared on The Herald News: 5 things you didn't know about Lizzie Borden and the murders