Did this Pearl Harbor sailor from Kentucky know this would be his last letter home?

Amy Cheshire still wonders about a letter that her Nelson County-born grandfather wrote to his 11-year-old son on Nov. 20, 1941. That 11-year-old would grow up to be her father.

Based at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, Navy Chief Pharmacist’s Mate James Thomas Cheshire II of the U.S.S. Oklahoma didn’t mention possible war with Japan in his letter. He was hungry for news from home.

“But it sounds to me as if he believed he might not be able to write another letter,” Cheshire said in a telephone interview from her home in San Diego, California. “I’ve been reading this letter for decades, but it wasn’t until recently when I was doing a timeline of the war that I realized that negotiations with Japan broke down on that day.”

Cheshire thinks the stalled peace talks in Washington might have prompted her grandfather to write home so longingly. Chief petty officers were known to be as salty as sailors get. They are the embodiment of what the Navy today calls "Warrior Toughness." But his missive to "Jim" − James Thomas Cheshire III − ends, “Love you an awful lot son and miss you so. Bye Bye for now, and be a good boy, Love, Dad.”

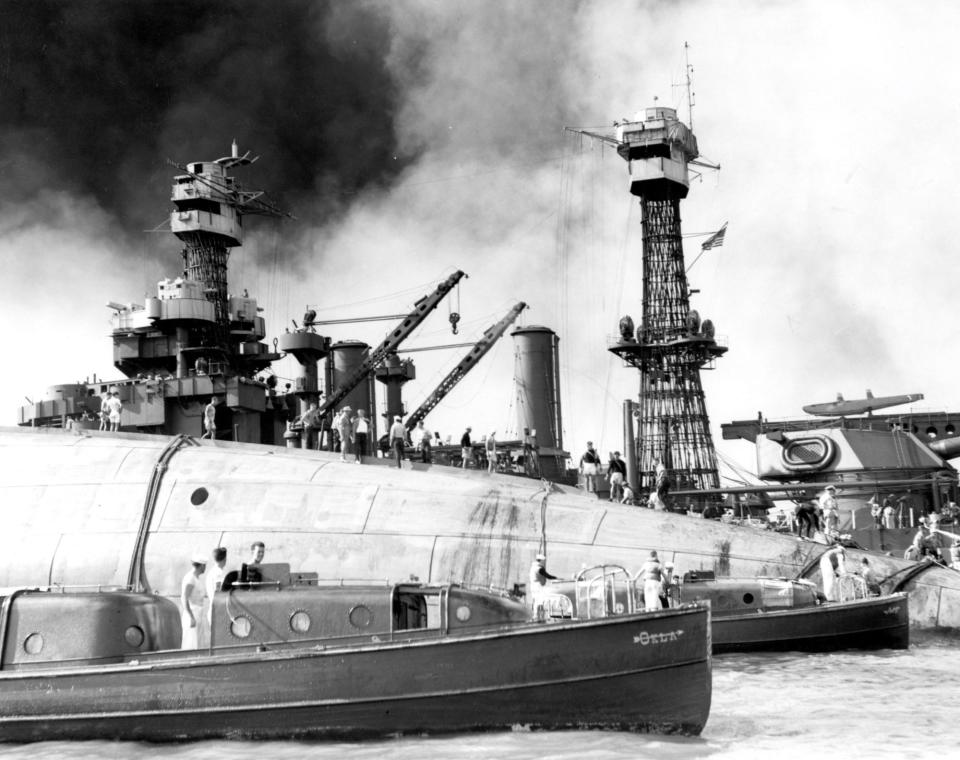

Seventeen days after he typed the letter on U.S.S. Oklahoma stationery, Chief Cheshire and 428 of his shipmates died violently aboard the big battleship. Its hull blasted open by eight torpedoes in the surprise Japanese air attack on Dec. 7 that pushed the U.S. into World War II, the “Okie” capsized and sank.

For years, the Navy was unable to identify most of the recovered remains, including Cheshire’s. They were ultimately buried in Honolulu’s National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, popularly known as “the Punchbowl,” where their names are among those recorded in the Courts of the Missing.

The chief’s granddaughter, a former aerospace systems engineer, is joined today with about 40 other relatives and their spouses at Arlington National Cemetery today to witness the burial of their loved one’s remains.

In 2015, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency disinterred the remains of Oklahoma crewmen for DNA analysis. Three years later, researchers were able to identify Cheshire, using Mitochondrial DNA samples supplied by two of Amy Cheshire's second cousins.

The DPAA has identified other Kentuckians who perished on the Oklahoma. Nine are in my book, “Kentuckians and Pearl Harbor: Stories from the Day of Infamy” (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2020).

“I was filled with emotion when my grandfather's remains were identified,” said Cheshire, who had been researching her grandfather’s life and military service for 30 years. She imagines she'll feel likewise when Cheshire’s remains, contained in a flag-draped coffin, are laid to rest in a marked grave following military rites at the country’s most famous military burial ground.

Cheshire’s research revealed that her grandfather, a native of the New Hope community, joined the Navy on May 28, 1919, four days after his 18th birthday. “I know how his death impacted my dad. He must have sat by the radio for weeks, hoping to hear that his father had been found and was alive.”

Also on the day he wrote Jim, the Japanese were secretly assembling the Pearl Harbor strike force, which centered on six aircraft carriers. The Sunday morning air raid killed more than 2,300 U.S. soldiers, sailors, airmen and marines and left in shambles the Pacific Fleet and Army, Navy and Marine air bases on Oahu.

In the page-and-a-half letter, Cheshire told Jim that he also had written to his mother, Marion, and sister, Peggy. The other two letters were lost, according to Amy Cheshire.

“He is sitting down and taking the time to write these three letters,” she said. “To me, he becomes very philosophical.” Cheshire was glad to hear Jim was “quite interested” in his school’s Nature Club. “…Most people like the nicer things of life and knowledge is one of them and the most important I think.”

Cheshire promised to send his boy some stamps for his collection. He was also happy to know that Jim was enjoying an evidently new typewriter. “Make sure you cover it every night for you know dampness and dust will cut down its efficiency.” But he admonished his son not to “go trying to oil it for that will just gum up the works.”

Far from home, Cheshire's thoughts turned to holidays: “Did you carry out your plans [for Halloween] and have lots of fun? I hope so anyway, for it isn’t every fellow who has a birthday and Halloween on the same day.”

More:'These people gave everything.' Louisville man works to tell stories of nation's WWII dead

The chief figured Jim and Peggy “were pretty well all set for Christmas since Mommie has been telling me about all the nice things she has been getting for the both of you." He was planning to send his kids “a little extra change so that you can surprise Mommie with a little gift.”

Cheshire also advised his offspring that he had “been saving a few more of the Wing [airplane?] pictures” and would send them after Jim mailed him a list of the ones he needed.

Nov. 20 was Thanksgiving Day in 1941, and Cheshire hoped his family enjoyed “a very fine…dinner and that the day was a pleasant one. Wish I might have been there to enjoy it with you, but maybe next year it will be different.”Cheshire concluded that “since there is nothing more to write about” he would “close for now.” He wanted Jim to write to him “soon and tell me all the news and what you are planning for Christmas and all that sort of thing for I’m always anxious to learn of your plans and what you are doing.”

Following the Pearl Harbor attack, Marion Cheshire got two Navy telegrams, the first before Christmas. That one said her husband was missing. The second wire, dated Jan. 30, 1942, confirmed that she was a widow: “After exhaustive search it has been found impossible to locate your husband James Thomas Cheshire chief pharmacist's mate US Navy and he has therefore been officially declared to have lost his life in the service of his country as of December Seventh Nineteen Forty One. The Department expresses to you its sincerest sympathy.”

Berry Craig is a professor emeritus of history at West Kentucky Community College in Paducah and an author of seven books and co-author of two more, all on Kentucky history.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Pearl Harbor sailor's last letter home and DNA identified his remains